Discover Literature

Discover Literature

8 Key Literary Elements in Every Written Masterpiece

WHAT GOOD READERS SHOULD LOOK FOR IN GREAT BOOKS

Good books transcend genre; their caliber doesn’t depend on their focus. Indeed, the very best books are often about nothing at all, other than planning a party (ahem, Mrs. Dalloway), and yet, they can transform the reader through their use of these eight key literary elements. Any written masterpiece should employ these techniques in abundance, synthesizing them to create a reading experience as rich as running your palm over a mossy boulder beside the ocean on an autumn afternoon as your love makes tea inside an amber-lit beach house.

This list will help eager readers hone their ability to recognize fine literature, and educate partakers of bad books on why they’re not reading good writing. I built this catalog from my inside knowledge as a writer, and from what has moved me as a reader. Both of these identities overlap reciprocally: I write what I would want to read, and I read what I would want to write. When I pick up any text, I’m looking for:

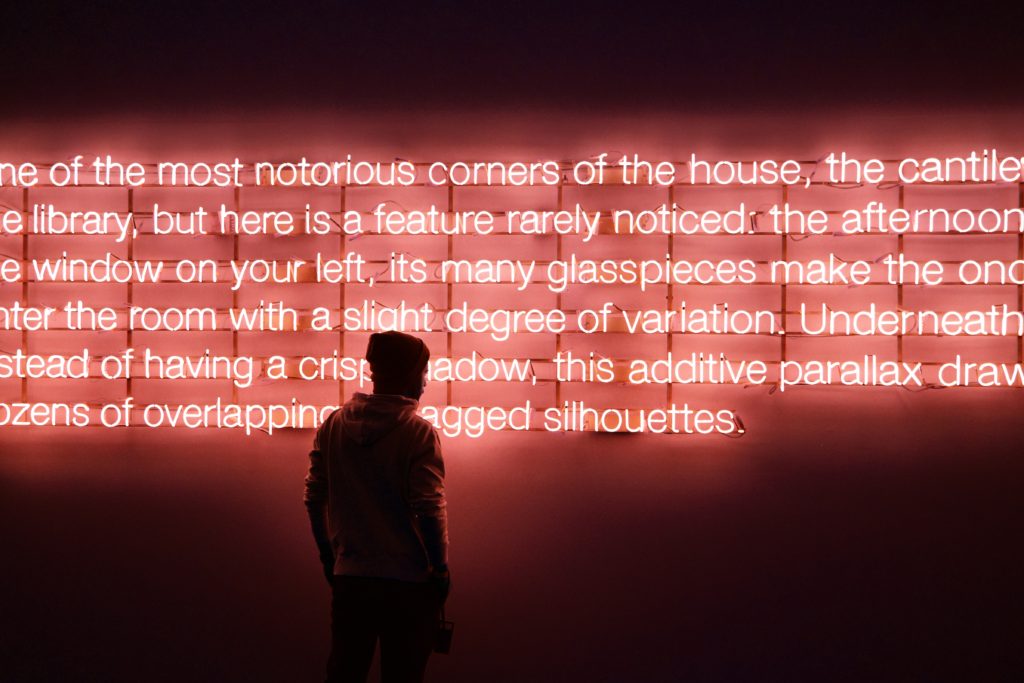

#1. LINGUISTIC POIGNANCY — THE APOGEE OF LITERARY ELEMENTS

Poets know that every single word is an opportunity to increase a poem’s vibrancy. We have much less linguistic leeway than prose writers because poems consist of so few words on each page. But good prose writers know that even though their documents contain thousands more words, every single one is still an opportunity to increase the text’s vibrancy. No matter the genre, all written masterpieces are a conscious combination of carefully picked words, like perennials plucked and placed upon the page. This means choosing “perennial” instead of “flower” or “linguistic poignancy” instead of “strong language,” and if you’re seeking to sophisticate your reading style, choosing not to read texts that ignore their bricks and mortar.

#2. ILLUMINATING IMAGERY — THE SENSATION OF WORDS

Imagery is the foundation of imagination. Books without it or that use it sparingly are lifeless, like fluorescent light glowing on linoleum by the Sprite cooler in a gas station after midnight. Books with tired imagery are simply boring — objects to be set down and forgotten in favor of writing that can render sensations freshly in every instance. Imagery is the product of the author’s observation and linguistic transformation from memory to page; good imagery will leave the reader imbued with hues and views, sea foam pink and green sparkling in their mind’s eye. Take this unassuming passage from Virginia Woolf’s The Waves, for example:

Rhoda dreams, sucking a crust soaked in milk; Louis regards the wall opposite with snail-green eyes; Bernard moulds his bread into pellets and calls them ‘people.’ Nelville with his clean and decisive ways has finished. He has rolled his napkin and slipped it through the silver ring. Jinny spins her fingers on the table-cloths, as if they were dancing in the sunshine, pirouetting.

The simple image of a “crust soaked in milk” conjures up the flavor the bread, shades of brown and white of the bread and milk, and the soggy texture of the liquid-soaked food. Louis’s “snail-green eyes” are both a fresh description of the color green and the image also evokes the spiral of the slug’s shell. The detail of Bernard’s bread-moulding into “pellets” instantly makes us feel the dough being rounded between our fingers. Nelville’s organization is embodied in the crisp image of a napkin “slipped through the silver ring,” while the imagery used to describe Jinny is kinetic and tactile with cloth, sunshine, and dancing fingers. Each instance of imagery stands up to close inspection as language calling to the senses, and also helps to build more dimensional characters in the book — a sign of a true literary masterpiece.

#3. PHILOSOPHICAL INQUIRY — THE DEPTH OF WORDS

Reading is an escape from the habitual that leads to a more intimate engagement with the mystical in the everyday.

Most readers can jab at a novel’s theme — usually something about life, love, and death. Most readers can also confidently point at a non-fiction book’s subject — This book’s about seeing ourselves as consumers and stuff like that, and now I really think I should clean out the garage and use those things I bought, you know? Themes are easy and obvious, but they never solely carry the weight of a good book. Textual masterpieces also weave wisdom throughout the entire text; they unfold in an amalgam of singular, aphoristic musings, planted amid the aforementioned illuminating imagery.

Take these brief lines, also from Woolf’s The Waves:

But nature is too vegetable, too vapid. She has only sublimities and vastitudes and water and leaves. I begin to wish for firelight, privacy, and the limbs of one person.

In these three lines that arrive in the middle of a section in the middle of the book, Woolf sets up a dichotomy between humans and nature, revealing our longing for the intimacy of another singular individual despite the unlimited poetic offerings of the vegetable and animal kingdom. Indeed, nature’s elements are too transcendent to be appreciated by us, succumbers to the basic urges of warmth and bodies. The Waves brims with sentences like these, making every reading moment a philosophical moment.

Unfortunately, most popular books are completely devoid of any type of epiphany, large or small, and revolve wholly around plot (see #7 below). But great writing has single lines that get underlined: such texts offer quotable philosophies that are equally revealing even when they’re extracted from the page.

#4. SONIC POWER — HOW WORDS SOUND

Sonic power deserves its own ode, though it’s technically one component of the linguistic poignancy literary element. Language is musical even when read mutely on the page, and poetic writing sings in the mind. When working with words, we use not chords, but combinations to create slant rhymes, internal rhymes, sibilance, alliteration, consonance, assonance, onomatopoeia, and so on. The best writing almost bounces along, carried by the momentum of its own tones. To eavesdrop on well-written words talking to each other is something like sitting beside a fountain that burbles at an enchanting frequency. An acoustically powerful book is impossible to ignore because it reverberates even after you’ve set it down.

#5. SYNTACTICAL FLUIDITY AND COMPLEXITY — HOW WORDS MOVE

People like short sentences. They really do. Short sentences are easy to follow. Commas complicate, or so people think, perhaps correctly. I even got dinged on my SEO score for this blog post about key literary elements because, according to Yoast, “31.4% of the sentences contain more than 20 words, which is more than the recommended maximum of 25%. Try to shorten the sentences.” But us refined readers aren’t part of that recommendation, and instead love the complex turns of thought that commas, hyphens, semi-colons, and colons enable. We want to follow the long idea to its end, and to do so, the text must flow and ebb and surge just like we think. In bad books, authors use excessive end-stops to dissect and dilute in compromise to most readers’ inability to hold a long string of thought; they keep their readers in the shallows. Then again, most writers don’t know how to escape the shallows either, or that there’s anything beyond a type of writing where they keep their toes firmly planted on the floor. But the best writers can go on and on and carry us along with them, sculpting the syntax into new structures, taking us out to sea without our even noticing, to a fathomless deep where the magnitude of the water reveals the heaviness of our own daily tenuousness.

#6. EMOTIONAL EVOCATION — HOW WORDS MOVE US

Here, things get murky. While all good books should stir up something inside the reader, all books that stir up something inside the reader are not good books. A text may be effective at catalyzing an emotion, but if they’re missing the other key literary elements that constitute fine literature, you aren’t reading literature. This bears repeating for lovers of popular fiction: just because a book made you feel something, doesn’t make it a good book. Let’s say you’re reading a thriller and the protagonist, an undercover detective who’s trying to break a drug ring and save a community, dies at the end. You’ve been following her for 284 pages, so you feel a certain loss when she passes, but also a joy that her work worked out; this particular drug ring is defunct. You read the last few pages and set the book down, wowed by the feelings evoked by the casualty of the fictional character. And then you go off and tell everybody you read a great book.

Please don’t. You didn’t read a great book — you just read a book that made you feel sad and glad.

On the 284 pages prior to the character’s death, the text was likely devoid of imagery, philosophy, poignant language, etc. Good writing contains all the other literary traits listed above, which build and culminate in the jouissance of an emotional response that doesn’t depend on the easy provocateurs of death, heartbreak, or romance to kindle titillations in your impressionable human heart. Instead, masterpieces grapple with subtle shades across the emotional spectrum, from the restless boredom of self-imposed solitude, to nostalgia’s sepia distortion of a moment under an awning with a stranger.

#7. PLOT IS NOT A CRUTCH — THE STRUCTURE OF A BOOK

This crucial literary element is a negative one: a masterpiece must ensure that it does not do this. Plot-driven books are the bane of any literary reader’s existence. Fantasy books, mysteries, and romances are the main culprits, and most U.S. readers eat that malarkey right up. When a book revolves around plot, which is the simple progression of action and events, it loses sight of itself as a text, including all of the opportunities to enlighten via language and musings. While good writing forces readers to linger and ponder, re-tracing their steps over the fallen leaves of sentences to engage with the kingdoms of fungi growing beneath rust and amber dropped foliage, plot-driven books force readers to keep on truckin’ so they can get on to get off to the thrill of the twist and turn. Plot tends to distract from the fact that a book is really quite poorly written and filled with insubstantial content; at best, these kinds of books are distractions from chores. But in the best books, the true masterpieces, the story line is something like a clothesline upon which the most vibrant colors, textures, and moods are hung, singing in flaps and snaps in the wind, and the reader is led through the nearby house, learning about the importance of the pot-bellied stove, the window that creaks, the chair where grandmother sat and watched the linens thresh.

#8. FIGURATIVE LANGUAGE — HOW IDEAS AMPLIFY EACH OTHER

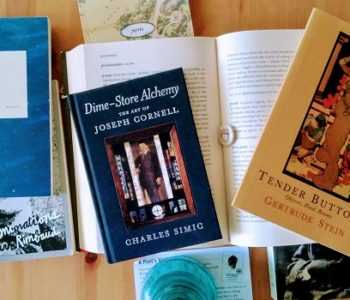

When you look at all of these key literary elements, poetry has the potential to be the best of the best writing: poems already de-prioritize plot; they’re designed to efficiently conjure up a mood; they challenge linguistic rules; they emerged from a musical/oral tradition; each line must hold its own as a profound idea; they’re grounded in imagery; and their relative brevity insists upon greater attention to diction. Another one of the hallmarks of a good poem is fresh figurative language — every budding poet knows that they should drop in a metaphor or a simile somewhere in their verse. Of course, they usually smear it on real hard, but when figurative language is done well, whether in poetry or more subtly in prose, it can tether two or more distinct ideas in an unexpected way, resulting in fabulous kaleidoscopic connections for the reader.

6 COMMENTS

THANK YOU for your perspective, your tips and examples, your knowledge! I write poems. You have helped

me enormousely. One question: can you have too many line breaks in a poem?

Ann Peck

This is one of the best writing blogs I have read in a while! Good to see someone is upholding high literary standards. I’ve been disappointed to find that postgraduate level writing courses put high emphasis on plot, pace and conflict, but very little emphasis on literary quality of writing.

Delicious writing about writing ^_^

Great article! I learned a lot from it. This is one of the best writing and literary blog ever!

Most awesome resource!

Deep bow of gratitude !

Thank you for this! Recommended an all-time favorite book to a dear friend only to have it returned with the snide comment: “It has no plot.”

I’ve been anxious wondering if it was such a masterpiece after all. This blog post reaffirmed it!