Book Review

Book Review

‘Ill Nature’ is Even More Vital in 2018

A BOOK REVIEW OF JOY WILLIAMS’S ILL NATURE ESSAY COLLECTION

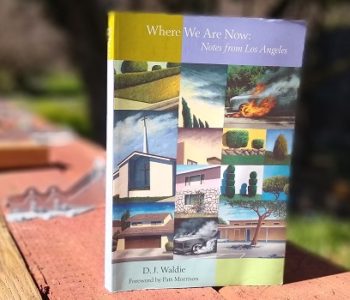

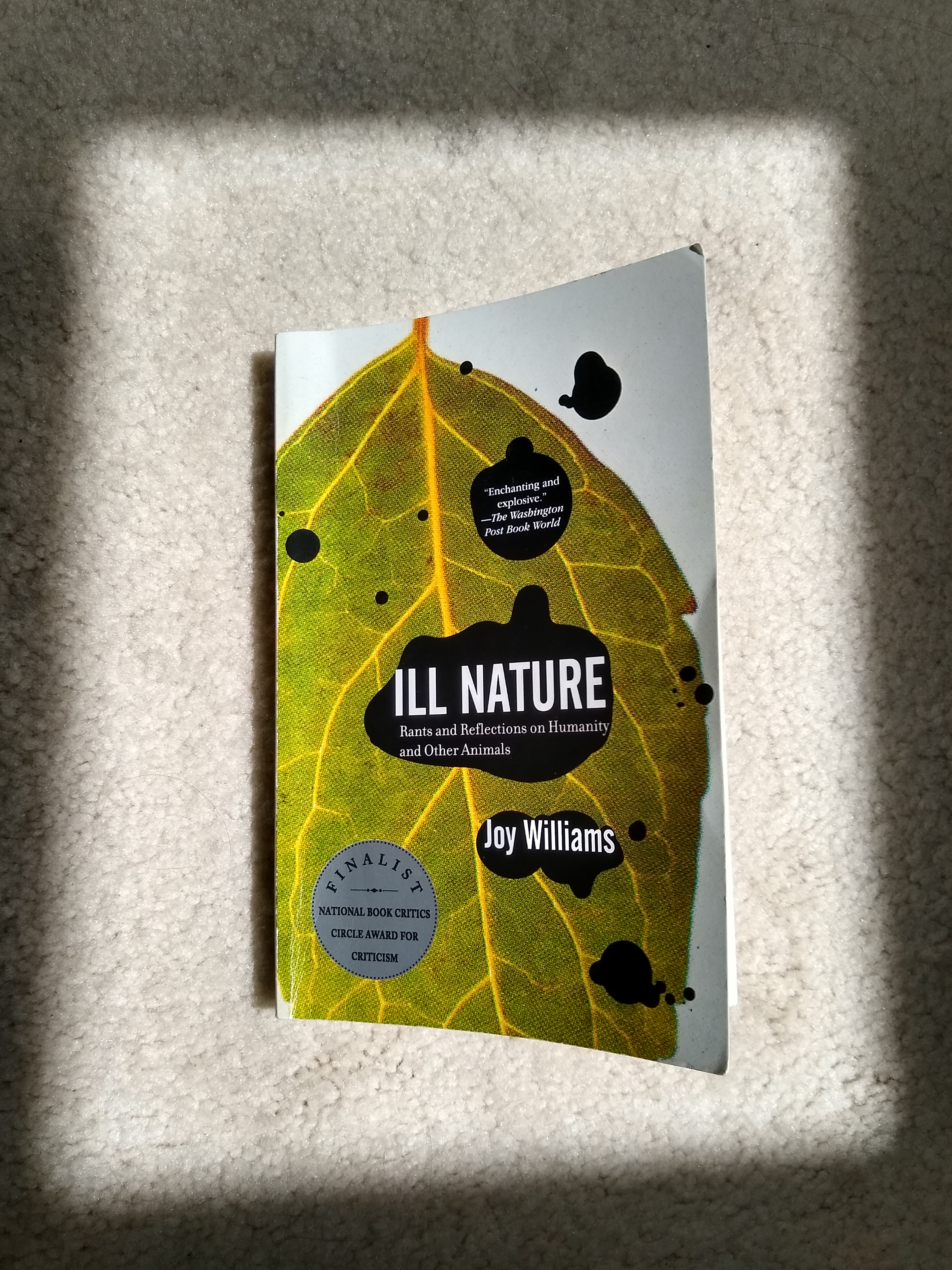

I found Ill Nature: Rants and Reflections on Humanity and Other Animals by Joy Williams tucked at the top of the nature section at the Iliad Bookshop in North Hollywood, CA. The book’s titular pun and subtitle reeled me in, since I’m a reader specifically seeking texts that grapple with the ways humans individually affect nature in the 21st century. Indeed, one of the most successful aspects of this book of essays by Williams, who is more widely known as a short story writer, is that it identifies the reader as a primary culprit in nature’s malaise.

In other words, even an average eco-conscious reader who picks up this essay collection will have to bear witness to the septic reverberations of their consumer footprint. This is ultimately a book that avoids “lecturing to the professor,” and instead reveals to the learned reader that they are as complicit as the hunter who every year will “turn the skies into shooting galleries and the woods and fields into abattoirs” (“The Killing Game”).

First published in 2001, and selected as a “Finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award for Criticism,” Ill Nature is built from 19 essays that range from more generalized condemnations of consumerism and animal treatment (e.g. “Save the Whales, Screw the Shrimp” and “The Animal People”), to deeply personal pieces (“Coral Castle” and “Hawk”), to one-page, poetic renderings of a grotesque natural plight (“Wildebeest” and “Audubon”).

Each essay form is effective in its own way: the rambling condemnations sparkle with humor and lead the reader through a gauntlet of evidence of their complicity in nature’s degradation; the personal pieces reveal instances in which the author was faced with the dilemmas that she decries the reader for; and the poetic renderings, my favorite, are poignantly swift epiphanies of overlooked beings and absurdities in nature –- in two pages we learn that, “The spoonbill is a simple and shy creature of many troubles, yet garbed in glory…it is not likely that Audubon saw many of them. In his remarks he noted that their flesh was oily and poor eating, and that they were difficult to kill” (“Audubon”). Yes, that Audubon.

Reading Ill Nature in 2018, I was perpetually haunted by the sense that each ecological emergency narrated by Williams is now much, much worse. For example, in “Safariland,” Williams explains that “It’s known that there were two million African elephants in 1970 and about 600,000 elephants are left. It could be said that these animals, mostly young and frightened and with little access to the accumulated knowledge of the past, have lost Africa,” and in “Neverglades” she reveals, “That the Everglades still exists is a collective illusion shared by both those who care and those who don’t. People used to say that nothing like the Everglades existed anywhere else in the world, but it doesn’t exist in South Florida anymore either. The Park, which millions of people visit and perceive to be the Everglades, makes up only 20 percent of the historic Glades and is but a pretty, fading afterimage of a once astounding ecosystem.”

In both cases, over 17 years, humanity has failed to remedy any of the critical emergencies of nature and have kept on trucking in their typical, self-indulgent manner. According to the World Wildlife Federation, there are now only 415,000 African Elephants, and the fact that, according to Defenders of Wildlife, there now just 100-180 Florida Panther adults and subadults in South Florida…the only known breeding population in the world — is just one indication that the crisis in the Everglades is escalating.

Ill Nature is not a salve for our environmental woes, nor does it intend to be. It’s an indictment and a warning, which makes for an effectively distressing reading experience. Too many general-reader ecological texts hand us the bad news that we’re destroying everything, but then buffer this with the good news is that if we do this and that, everything might turn out okay. Williams instead strands us in the murkiness of our own guilt, a realm where:

When I think about Africa what I think is wildebeest – that wild, incomprehending, incomprehensibile thing that thirsts. And I think that when you’re talking about darkness, the blackness of darkness, you’re talking about wildebeest (not elephants, the monumental moral innocence of elephants, but wildebeest), for wildebeest are at the great empty heart of blackness, the heart of its nothingness, dying over and over again against the indifferent fence with the water just beyond it.”

(“Wildebeest”)

In this deeply troubling domain, Williams ensures that we feel as helpless as the animals we’re helping to eradicate though apparently benign consumerism.

Despite this necessary gloom, Williams is an acutely humorous writer. Take this passage from “Neverglades” for example:

The Everglades was lost, but it was still there and the notion took hold that with good will and a little tinkering it could be resurrected. To some degree. The public became increasingly educated about its intrinsic worth. For example, around this time a group of sixth-graders visiting the Park composed a poem that was rendered on a bronze plaque and erected at the Pay-Hay-Okee boardwalk overlook:

Every time you go to a place

That has those animals on its face,

It makes you laugh and cheer

Because it’s fun out here.

We love you Everglades!

We’ll help to save the place!Nice work, children! Lovely.”

(“Neverglades”)

Or, in “The Animal People,” which presents a satirical version of how organizations such as the American Medical Association and the FDA “have an idea of what a day in the life of an animal rights activist is like, and they want to share it with you…

As the day wanes, they go home and work for a while on the “Transitions” section of their underground zine, writing loopy obits like Emily the hen enjoyed two years with her human friend Sally before taking spirit form and leaving the material plane…Evening finally comes and they sit eating their tofu burgers in the messy house they share with six dogs and eleven cats…”

(“The Animal People”)

Beyond the scathing humor, in both instances, Williams’s natural knack for storytelling is apparent, and indeed, many of the essays read like intimate stories of a particular facet of nature.

In Ill Nature, Williams also has a strong command of the poetic, such as in the brief “One Acre,” an essay about a plot of land in Florida that she let flourish unhindered:

“Though the wall did not receive social approbation, its approval from an ecological point of view was resounding. The banyan, as though reassured by the audacious wall, flung down dozens of aerial roots. The understory flourished, the oaks soared, creating a great, grave canopy. Plantings that had seemed tentative when I bought them from botanical gardens years before took hold. The leaves and bark crumble built up, the ferns spread. It was odd. I fancied that I had made an inside for the outside to be safe in. From within, the wall vanished; green growth pressed against it, staining it naturally brown and green and black. It muffled the sound and heat of the road. Inside was cool and dappled, hymned with birdsong…”

(“One Acre”)

The passage continues, as it should, with similarly effulgent imagery, figurative language, and fluid syntax: Williams knows when to let the poetry run free.

My only qualm with Ill Nature was the inclusion of a few pieces that felt too far removed from the other book’s essays to feel at home in the collection. For example, “Why I Write,” the finale essay, doesn’t end up saying much about the purpose of writing in relation to the purpose of the rest of the book; it offers a more generalized view of the importance of writing, so that it feels like it’s still the “Why I Write” that “first appeared in Oxford American but was originally commissioned for the anthology Why I Write edited by Will Blythe (Little, Brown), where it subsequently appeared,” and not the final statement in Ill Nature, a book reflecting on humanity’s apathy towards the variegated life we share this earth with. But overall, Ill Nature is an enduringly urgent, humorous, troubling-in-its-dark-clarity lens through which to view the literal world, and an incisive incentive to each live differently, in order to present ourselves with an illusion that we might just be able to fix things.

If this Ill Nature book review prompts you to donate, perhaps to one of the wildlife organizations I linked to above, the reality is that your donation will do very little — those are just coins to assuage your guilt as long as you keep living the same consumptive lifestyle. As Williams explains in the collection’s opening essay:

“The ecological crisis cannot be resolved by politics. It cannot be resolved by science or technology. It is a crisis caused by culture and character, and a deep change in personal consciousness is needed…You must change. Have few desires and simple pleasures. Honor nonhuman life. Control yourself, become more authentic. Live lightly upon the earth and treat it with respect.”

(“Save the Whales, Screw the Shrimp”)

Reading Ill Nature will help you recognize the weight of your appetite, habits, desires, concepts of home, travels, and ignorance. After putting the text away, it’s up to you to decide if you want to not only unburden yourself, but also the living creatures that must bear your mass.

ISBN of Edition Read: 9780375713637

Notes of Oak Literary Blog Book Review Score for: Ill Nature by Joy Williams

8/10