Discover Literature

Discover Literature

Prose Poetry: What’s the Point?

LET’S INVESTIGATE PROSE POETRY – THAT OXYMORONIC, SLIGHTLY OBNOXIOUS LITERARY FORM

Prose poetry. It sounds like an oxymoron. Like jumbo shrimp. Or plastic silverware. Or a soothing Lithuanian folk song. But it does indeed exist, having been wrought into existence by the exceptional creativity or pure boredom of writers. But why? Why taint the dainty lines of poetry with the blocky bulk of prose? Let’s find out by looking at the form’s history, major works, essential characteristics, and a literary analysis of Robert Bly’s prose poem “Warning to the Reader.”

This post is quite long, so you can jump to any of the main sections here:

A LONG-WINDED PROSE POETRY HISTORY

THE GRANDFATHER OF PROSE POEMS

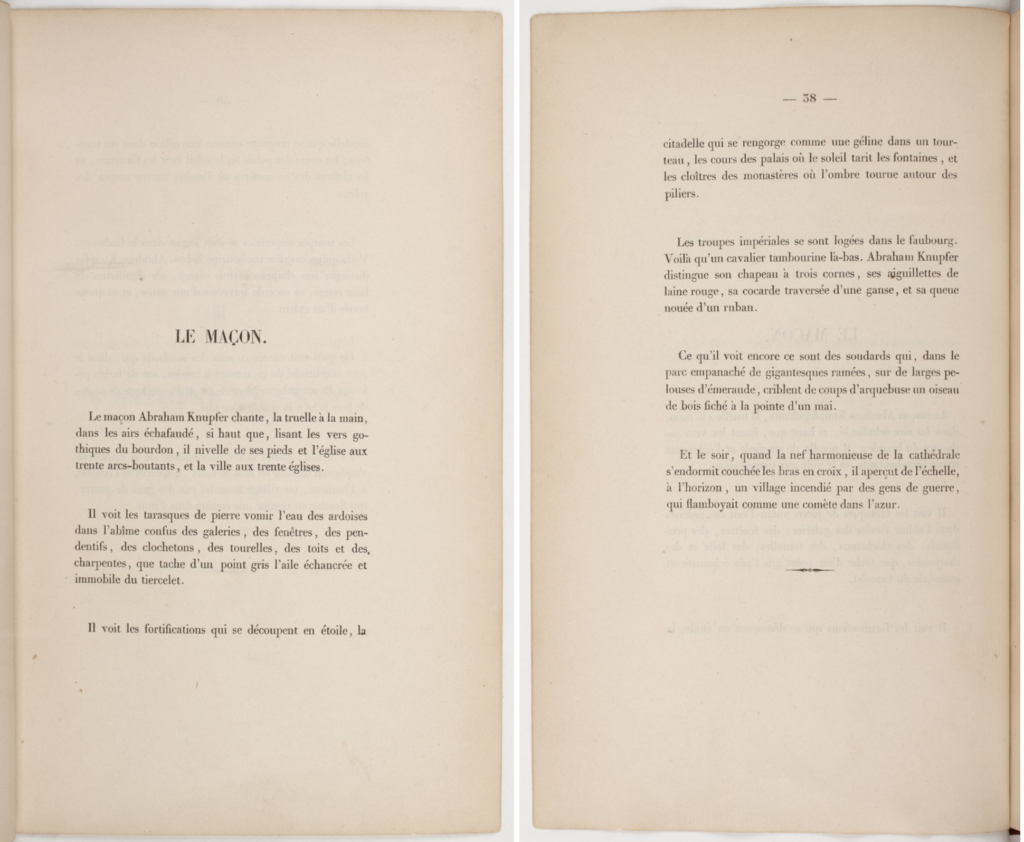

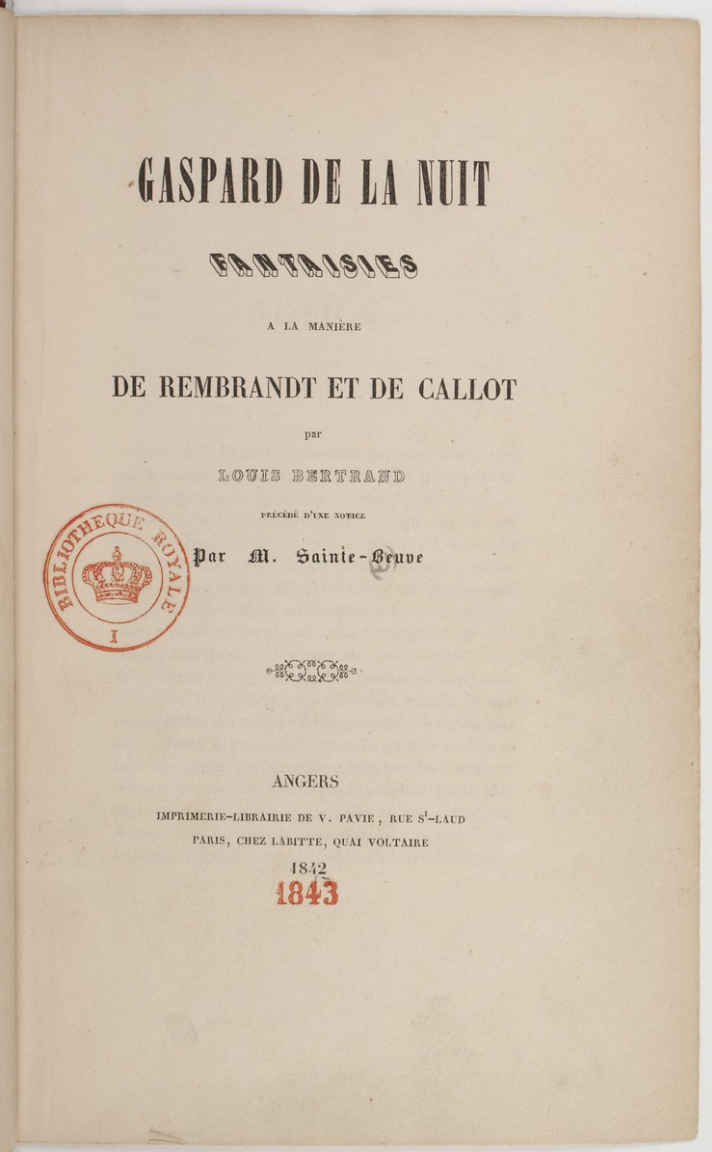

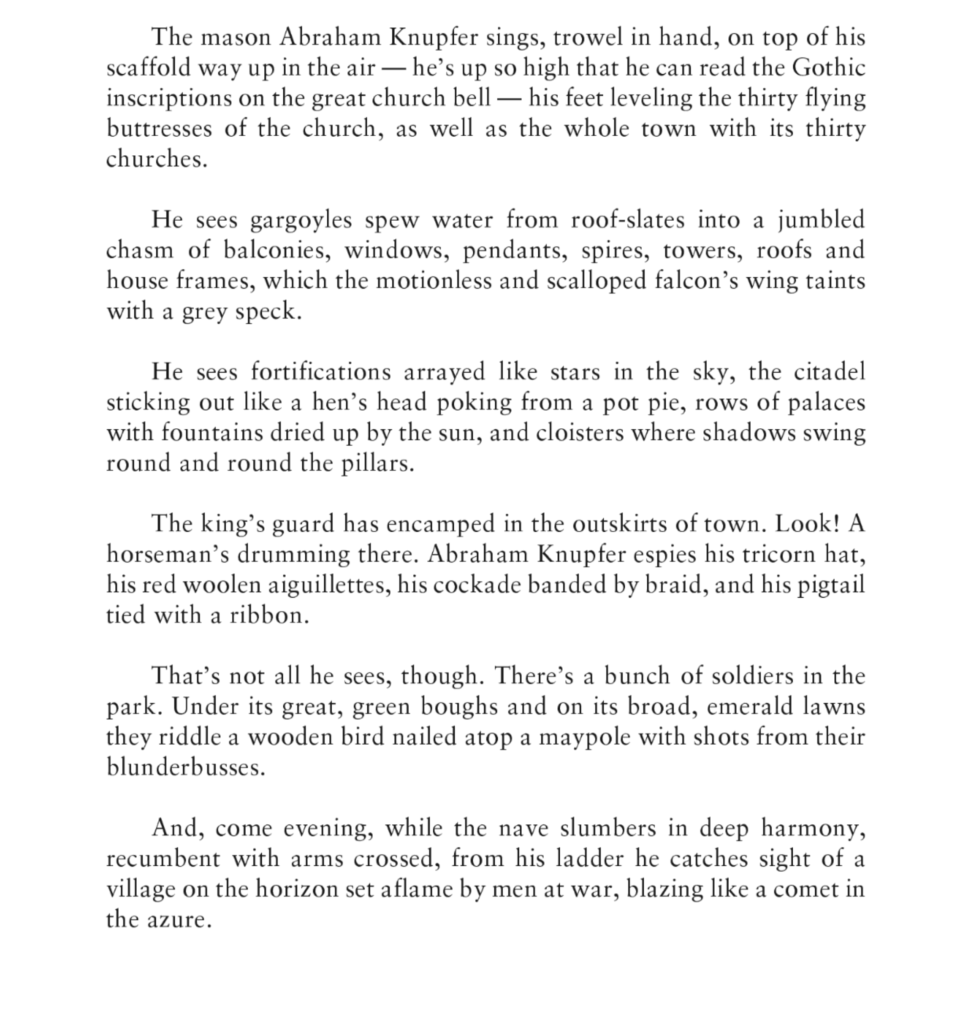

In Western literature, Aloysius Bertrand’s woefully obscure book, Treasurer of the Night: Fantasies in the Manner of Rembrandt and Callot (Gaspard de la nuit) (1842), is generally considered to be the first work of prose poetry. Bertrand was a stereotypical poet: gaunt, phlegmy, lonely, and doomed to die young in penniless obscurity. He honed his strange book of poetry for years, whittling his words into an exciting new form and bribing his would-be publisher with a stoop sonnet, but his magnum opus was destined to be released posthumously. The book consists of six sections, each containing what can only now be called prose poems, all of which frolic through a gnarly orgy of medieval imagery. Courtesy of the World Digital Library, here’s the poem “The Mason” from the “Flemish School” section of Bertrand’s book in the original French:

And here’s the translation:

You’ll immediately notice that Bertrand doesn’t employ enjambment – his lines run right to the margin. However, he maroons each paragraph in a sea of white space. According to Alan Ziegler in his excellent essay on the “Origins of the Prose Poem,” “In readying the book for publication, Bertrand instructed ‘Monsieur typesetter to cast large white spaces between these couplets as if they were stanzas in verse.'” From this, we realize how critical white space is to the perception that a text is a poem.

Secondly, although Bertrand never explicitly labeled his work as “prose poetry,” it seems that he wanted what he called his “new type of prose” to look and feel like poetry, even if the quadrate elements on the page were clearly neither couplets nor stanzas. Indeed, you can’t see them as anything other than paragraphs — occasionally single-line paragraphs — but paragraphs nonetheless, based on their indent, lack of line breaks, and status as self-contained thematic units.

With meter, rhyme, and enjambment thrown out the window in one great, modern heave, the only other way to ensure that the content could be read as something that wasn’t just prose, was to slather it in the remaining techniques utilized by poetry. Namely, figurative language, imagery, and strong diction. These elements exist in prose, but in poems, they exist in their most potent concentration, primarily because of the brevity of that form.

Thus, we get lovely similes in Bertrand’s work like, “the citadel sticking out like a hen’s head poking from a pot pie,” and diction such as, “they riddle a wooden bird nailed atop a maypole with shots from their blunderbusses” (kudos to Gian Lombardo for this deft translation). Indeed, the entire book brims with wonderful lines, such that the only thing you can really call it is a collection of poetic prose, or perhaps, prose poetry.

CHARLES BAUDELAIRE’S LITTLE POEMS IN PROSE

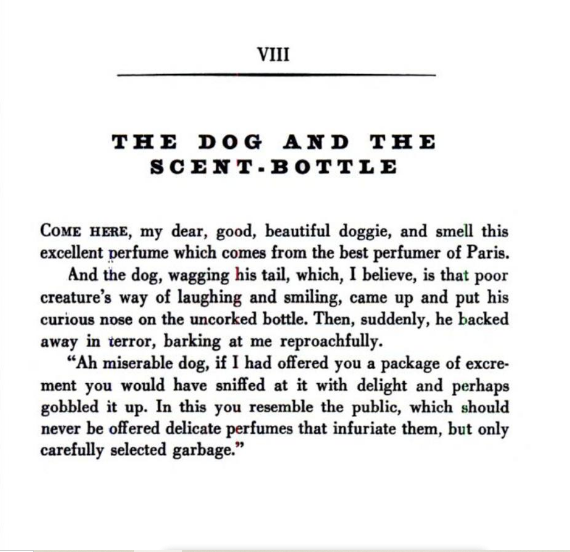

However, as the old saying goes, it’s not a prose poem until Charles Baudelaire calls it one, and heavily relies on your work as inspiration for his own version of prose poetry. In the late 1850-60s, building upon Bertrand’s innovations, Baudelaire began writing and publishing prose poems, 50 of which were eventually collected posthumously in Little Poems in Prose (Petits Poèmes en Prose) (1869) (alternatively known as Le Spleen de Paris). Baudelaire is a critical player in the history of prose poetry because not only did he produce the next big batch of this new form, he grounded it in intent. As the Poetry Foundation notes, “Baudelaire is the first poet to make a radical break with the form of verse by identifying nonmetrical compositions as poetry.”

In a letter from Baudelaire to Arsene Houssaye, which was later used as a kind of preface to Little Poems in Prose, Baudelaire notes that:

It was while running through, for the twentieth time at least, the pages of the famous Gaspard de la Nuit of Aloysius Bertrand (has not a book known to you, to me, and to a few of our friends the right to be called famous?) that the idea came to me of attempting something in the same vein…Which one of us, in his moments of ambition, has not dreamed of the miracle of a poetic prose, musical, without rhythm and without rhyme, supple enough and rugged enough to adapt itself to the lyrical impulses of the soul, the undulations of reverie, the jibes of conscience?

And thus was born the prose poem. Whereas Bertrand’s paragraphs are like little rafts floating in the white wake of verse, Baudelaire’s prose poems look more akin to newspaper blurbs:

You’ll also notice that this example immediately feels less poetic than Bertrand’s prose poem, and this tends to be the case throughout Baudelaire’s book. This is not so much a matter of the absence of spaces between paragraphs, or the fact that many of the prose poems stretch onto 2-3 pages, but rather the deficit of other poetic elements. For example, in the above piece, while the objects that make up the image of “the dog and the scent-bottle” have a nice concreteness, there’s no figurative language, little alliteration, and the diction feels more muted and predictable than Bertrand’s. It seems that although Baudelaire’s definition of a prose poem was ideal, his execution was not – I think.

In any case, it doesn’t matter what I think because Baudelaire’s well-read work set the precedent for prose poetry over the next century and a half. He established prose poetry as a valid form of literature, with the form taken up as challenge by various authors ever since. The timeline below plots seminal works that contain prose poems — including some texts not explicitly labeled as such by their writer.

TIMELINE OF DEFINITIVE PROSE POETRY TEXTS

Treasurer of the Night: Fantasies in the Manner of Rembrandt and Callot by Aloysius Bertrand

As discussed above, this is considered the first attempt at prose poetry in Western literature. I like it.

Little Poems in Prose by Charles Baudelaire

As discussed above, using Bertrand as a springboard, Baudelaire sat down and tried to write “poetic prose.” Eh, it’s alright.

Illuminations and Other Prose Poems by Arthur Rimbaud

An outspoken fan of Baudelaire, Rimbaud wanted to rewrite the rules of poetry. His greatest attempt at this is in the 40-odd poems that make up Illuminations, most of which are prose poems. After all, if you’re going to redefine poetry, why not test the boundaries of the form in the process? Alchemistic, chimerical, synaesthetic, imagery-rich, and occasionally in need of revision, Rimbaud’s poems are what Baudelaire imagined prose poetry to be. Rimbaud gutted the prose form of its narrative structure, so his content sounds noticeably more lyrical than Baudelaire’s pieces. Today, his writing feels a bit modifier-gilded and exclamatory, but it does contain gems such as:

“Roads bordered by walls and iron fences that with difficulty hold back their groves, and frightful flowers probably called loves and doves, Damask damning languorously, — possessions of magic aristocracies ultra-Rhenish, Japanese, Guaranaian, still qualified to receive ancestral music — and there are inns that now never open any more, — there are princesses, and if you are not too overwhelmed, the study of the stars—the sky” (from “Metropolitan” translated by Louise Varèse, New Directions Publishing – 1957).

Tender Buttons by Gertrude Stein

One of the most fascinating and poetic texts ever written, Stein’s Tender Buttons unsettles format, syntactical structures, narrative, meaning, and the reader. Utilizing repetition to reveal and distort, Stein’s book glints with magnified views of the everyday. Reading it feels like digging dirt back with your fingers, handful after handful, until you feel the gloss of a carafe, and pull it out to reveal it is but a shard, a half, a loss, a dirty gain under your fingernails.

Most importantly, Tender Buttons is a book of prose poems. Whereas both its predecessors and descendants frequently try to compensate for the stuffing of poetry into a prose skin by imbuing their prose poems with kindergarten clarity of meaning – or at least image – Stein has disturbed basic prose sentence structures. Here’s the first few lines from “BREAKFAST”:

“A change, a final change includes potatoes. This is no authority for the abuse of cheese. What language can instruct any fellow.

A shining breakfast, a breakfast shining, no dispute, no practice, nothing, nothing at all.

A sudden slice changes the whole plate, it does so suddenly.

An imitation, more imitation, imitation succeed imitations.”

Not only is Tender Buttons syntactically innovative, the structure of the prose poems self-consciously mutate over the course of the short text. The book is organized into “OBJECTS”, “FOOD”, and “ROOMS”, and the first section features poems that stick to a handful of sentences/paragraphs. They feel relatively safe compared with the content to come. The second section begins with a list of ingredients or titles, followed by prose poems built around many-sentence paragraphs. The text suddenly becomes blocky – literally more opaque – and the organization begins to mimic the compulsive content; in this “FOOD” section, we neurotically repeat poems, as if we are trying to uncover exactly what they are — here’s a “CHICKEN” poem, and another “CHICKEN” poem, and another and another. In the final section, “ROOMS,” the text sheds all titles, so it functions as one enormous prose poem. However, because the previous two sections established the paragraphs as little prose poems, we are able to read this giant piece of prose as poetic — as many little prose poems — and it’s up to us, the reader, to determine where each poem begins and ends. This onus on the reader, this ambiguity of the prose poem, continues to this day, but Stein identified it and presented it perfectly way back in 1914.

Anyways, read this book if you want to be smart.

Men, Women and Ghosts by Amy Lowell

This is a book of lyrical bric-a-brac, where modified verse mingles with free verse and prose pieces of varying length. In her Preface to the text, Lowell notes that, “A good many of the poems in this book are written in ‘polyphonic prose’…the word ‘prose’ in its name refers only to the typographical arrangement, for in no sense is this a prose form. Only read it aloud, Gentle Reader, I beg, and you will see what you will see.”

Lowell was one of the first writers to use this term, which now has the Merriam-Webster Dictionary definition of, “A freely rhythmical prose employing characteristic devices of verse (such as alliteration and assonance).” If you ask me, that sounds exactly like a prose poem. It’s also important to note that Lowell, in her instructions to the Gentle Reader, establishes that sonic power — out loud power — can determine whether prose is read as a poem. Here’s some polyphonic prose from the “Bath” section of “Spring Day”:

“Little spots of sunshine lie on the surface of the water and dance, dance, and their reflections wobble deliciously over the ceiling; a stir of my finger sets them whirring, reeling. I move a foot, and the planes of light in the water jar. I lie back and laugh, and let the green-white water, the sun-flawed beryl water, flow over me. The day is almost too bright to bear, the green water covers me from the too bright day. I will lie here awhile and play with the water and the sun spots.”

Kora in Hell: Improvisations by William Carlos Williams

Primordial, ambiguous, and possibly a book of prose poems, WCW himself didn’t know what the hell he had created, and labeled the content “Improvisations” as compromise. The book’s rambling Preface is both a butt-hurt response to criticisms from the likes of H.D. and Wallace Stevens, and contains such theoretical doozies as, “Thus a poem is tough by no quality it borrows from a logical recital of events nor from the events themselves but solely from that attenuated power which draws perhaps many broken things into a dance giving them thus a full being.”

Still, in Kora, WCW writes what every poet should want a prose poem to be – hyper-concentrated lyrical elements that conjure up an indescribable torrent of feeling and sensory impressions. Here’s a sample from Improvisation IV, 2:

“How smoothly the car runs. And these rows of celery, how they bitter the air—winter’s authentic foretaste. Here among these farms how the year has aged, yet here’s last year and the year before and all years. One might rest here time without end, watch out his stretch and see no other bending than spring to autumn, winter to summer and earth turning into leaves and leaves into earth and—how restful these long beet rows—the caress of the low clouds—the river lapping at the reeds. Was it ever so high as this, so full? How quickly we’ve come this far. Which way is north now? North now? Why that way I think. Ah there’s the house at last, here’s April, but—the blinds are down! It’s all dark here. Scratch a hurried note. Slip it over the sill. Well, some other time.”

Soap by Francis Ponge

Soap (Le Savon) is just one of many texts in which French poet Francis Ponge examines the minutiae of everyday objects through the lens of prose poetry. Throughout his oeuvre, his subjects range from mud to tables, telephones to crates. For Ponge, the prose-poem form is functional and vital; it’s the microscope necessary to hone in on the tiniest ecstatic details of the most mundane things. If you think prose poetry doesn’t need to exist, you haven’t read Francis Ponge.

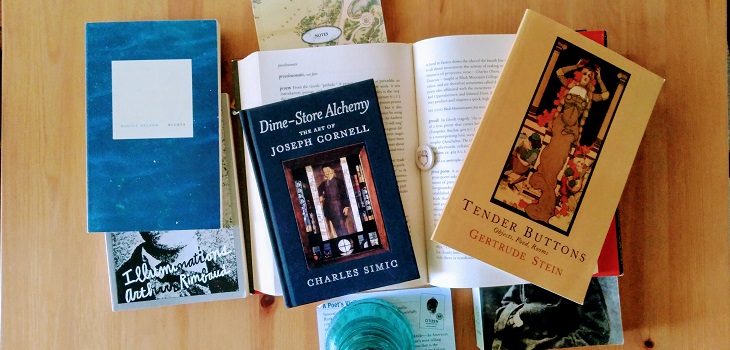

Dime-Store Alchemy: The Art of Joseph Cornell by Charles Simic

Although it’s technically categorized as criticism, (the copyright page states “1. Cornell, Joseph–Criticism and interpretation”) Simic’s curious, and beautiful little book is really a collection of prose poems that evoke Cornell’s own shadowbox art. Simic’s assembles textual fragments of images, facts, and curiosities, all of which have depth and tangibility that the reader can sense, but can’t touch. Some of the prose poems are ekphrastic pieces based on Cornell’s art, while others ruminate on biographical bits about Cornell’s creative processes. The text includes photographs of Cornell’s work, further blurring the lines between biography, art criticism, prose, poetry, reality, and dreams. Not only is Dime-Store Alchemy a pleasure to read for lines like, “Insomnia is an all-night travel agency with posters advertising faraway places,” it also establishes prose poetry as a new form of non-fiction.

Citizen: An American Lyric by Claudia Rankine

Citizen is one of the most widely-read books containing prose poetry published in the 21st-century. In this text, Rankine utilizes images, essays, and prose poems in order to probe at the racism ingrained in American culture. Here, the prose poetry form is utilitarian; it provides a particular and incisive angle of illumination. Rankine’s use of different literary and visual forms throughout the book underscores the need for variegated lenses in order to see the trenchant pervasiveness of racism.

STILL, WHAT THE HELL IS A PROSE POEM?

For me, the prose poem is a pure literary creation, the monster child of two incompatible strategies, the lyric and the narrative. On the one hand, there’s the lyric’s wish to make the time stop around an image, and on the other hand, one wants to tell a little story. The aim, as in a poem written in lines, is to arouse in the reader an unconquerable desire to reread what he or she has just read. In other words, it may look like prose, but it acts like a poem.”

Charles Simic, from the essay “The Poetry of Village Idiots” (1996)

If you read through my rambling history and still don’t know what a prose poem is, join the crowd. As you can guess from the various monikers writers have christened it with and Simic’s uncertain definition above, there’s a good chance that nobody can quite pin down this literary form. We just know it’s distinct enough that it has to be qualified by the word “prose,” whereas a poem is just a poem. But we can at least get closer to the prose poem’s essence through some good old pretending like we know what we’re talking about — ahem, I mean William Carlos Williams-ing — ahem, I mean juxtaposing forms to illuminate their differences.

Prose Poetry vs. Poetry – Key Differences

A prose poem is exactly what it sounds like: a poem presented in prose form. This means it typically employs all the devices that make a traditional poem, poetic – whether free verse or metered. That can and should include undiluted imagery, figurative language, sonic power, robust diction, a reference to a potato or an oak tree, and a revelation. It’s quite the potent bushel. The only element missing, and the only element that will always be missing, is enjambment. If you begin breaking lines, however badly, before they reach their natural syntactical conclusion, you no longer have a prose poem — you have an (attempt at) a poem.

So what is the effect? What is the point of writing a prose poem? What happens when a writer presents the above poetic ingredients in a prose container like fruit cocktail in a mason jar? It would be nice to say that the below are easily identifiable differences, but rather, these are possibilities that can arise when you choose this form.

Latitude: Prose poems occupy more horizontal space than traditional poems. Every single line creeps to the edge of the page through grammatical momentum. The consequence, though not an obligation, is more words less strategically placed. Thus, because of their format, prose poems feel relatively more loquacious. Writing an enjambed poem is like carefully pipetting strange liquids into test tubes, and writing a prose poem is like pouring them all into one beaker and topping the elixir off with a little whiskey because it needs a tint of amber.

Velocity: Prose poems, though more verbose, tend to read more quickly than traditional poems because line breaks create hesitation. Breaking a sentence at unexpected syntactical points births pauses. They are precipices that the reader must leap from carefully if they want to land in the full depth of words just below. In contrast, prose poems carry on, carry on, carry on. Even if they’re punctuated by a staccato of short sentences, there’s little white space to navigate. When it appears, it arrives where we expect it: at the start of a paragraph. You need not worry that a line is going to leave you hanging in a prose poem, and so you may proceed more rapidly.

Noise: In their fullness, their completeness, prose poems are more muffled. They contain less exposed end-words than an enjambed poem, and so there are less opportunities for resonance. Unbroken sentences cannot peal against the silence of the page. They must talk amongst themselves and conjure up a different, more mellow euphony.

Appearance: Enjambed poems are barbed. Shapes form on the page through both the presence and absence of text. Meaning dwells in the white space, or in the ragged edge of a stanza versus a neat edge. Line-broken poems cascade. They gather and release. They are conspicuously poetic. On the other hand, prose poems look like paragraphs. You can’t always identify a prose poem just by looking; you must begin reading. Still, if you like neat edges, if you like alignment and fullness, a prose poem can feel more inviting.

Temperament: Everyone reads prose more than they read poetry. Prose is pretty people talking. Poetry is ugly people brooding. As such, prose poems feel more natural. Easier. No matter how many enjambed poems I read, I approach each new one carefully, as one handles a glass with sharp edges. Prose has cushion, bumpers, a substantial rump, and thus, so does prose poetry. It allows itself to be read less precisely, though more comfortably. A hardwood chair versus a cushioned armchair; if you’re neurotic, you’ll certainly prefer the former.

Accessibility: One could argue that the prose poem we’ll look at below by Robert Bly is only a prose poem because it was printed in The Prose Poem: An International Journal. If it appeared in Notes of Oak: A Short Story Journal, it would be read as a short story. However, if an enjambed poem appeared in Notes of Oak: A Short Story Journal, it would be read as a misprint or an imposter. Structurally, poems are more conspicuously themselves than prose poems. They can’t hide their naked edges. Prose poems, garbed in the boas and dark pearls of full-stopped sentences, can blend in with the cool crowd of fiction, essays, social media posts, blurbs, and novel snippets. This is where prose poems excel: they can infiltrate and surprise the average reader with their concentrated lyricism.

Meaning: I’ve detailed in another blog post how enjambment, in its carrying over of significance from one line to the next, creates prismatic meaning. When you sunder a sentence in its center, when an unexpected word is left to jut, understanding can penetrate at different angles and connotative refraction can occur. Prose poems are literally more opaque. There are less surfaces where meaning can multiply. Without the ability to do this, prose poems must be embedded with meaning. They must narrate meaning like silver veins running through ore. Thus, the reader approaches the prose poem with a pickaxe, and the enjambed poem with a feather duster.

Malleability: The aesthetic experience of reading text morphs based on the vehicle through which you encounter the content. For example, if you’re reading this blog on your phone, it’s a “longer” post than for someone reading it on their computer, who is experiencing a “wider” post. Superficial differences, such as typeface, can alter the reading experience, and to some extent, they can alter the words’ connotative meaning. However, prose is much more malleable than poetry: because prose doesn’t depend on particular line breaks, it can fit into more variegated containers without drastic mutations in its meaning.

Poetry, in contrast, is persnickety and peculiar. If you stuff it onto a different-sized page, you can force its lines to splinter at unintended points and change the author’s meaning — you can pervert what an enjambed poem is trying to say merely through medium. Prose poems don’t suffer from this idiosyncrasy and thus you can send them out into the world without worrying (as much) that some small-time blog author is going to post a distorted version of your poem on their site.

Prose Poetry vs. Prose – Key Differences

Let’s move to the “prose” part of prose poems and try to figure out how these two modes of writing are distinct. Various dictionaries associate “prose” with the term “ordinary.” Prose is a plain, everyday mode of communication — a note left on the coffee table, the instructions on the back of your frozen meal, and so on. The linguistic authorities also define prose by what it is not. They declare that prose is not poetry. From this, we can deduce that poetry is an extraordinary thing — and as a hybrid of these two modes of communication, the prose poem is extraordinary organs tucked inside a familiar skin. So how does it differ from its other parent, prose?

Concentration: As I’ve mentioned above, the prose poem’s primary connection to poetry and deviation from ordinary prose is its concentration of poetic devices. This includes rhyme, rhythm, alliteration, consonance, cacophony, euphony, onomatopoeia, repetition, metaphor, simile, imagery, allusion, metonymy, personification, anaphora, hyperbole, litotes, diction, symbols, synesthesia, ambiguity, anastrophe, antanaclasis, asyndeton, juxtaposition, and polysyndeton (yeah, even I didn’t know that was the repetition of conjunctions in close succession), to name a few devices. All of these elements can and do occur in prose, but the prose poem will use them more often, more deliberately, and more effectively.

Truncation: Prose poems tend to be shorter than other prose forms such as essays, short stories, and novels. There’s no rule that a prose poem can’t continue for pages, but if it does, the length begins to dilute the concentration of the poetic elements detailed above. Even though an author can technically sustain these elements for as long as they have stamina, a truncated appearance compared to a traditional piece of prose signals to the reader that the content will pack more into a smaller space. By miniaturizing content, the prose poem declares that it will be extraordinary in less space — something that poetry does best.

Disorientation: Exposition takes time and space, as does explanation. In its relative economy, the prose poem doesn’t have patience to build plot. A prose poem drops the reader into a scene whose antecedent and precedent narrative likely don’t exist; if the prose poem is part of a book of prose poems with a cumulative narrative arc, the spaces between each prose poem still mince up this arc. The result is an exciting feeling of disorientation and disconnection typically not found in prose. We expected chronology, but we were given a mere moment, and how dearly we cling to its substance.

Indentation and Blankness: Although prose poetry doesn’t use enjambment, one could argue that it does use a perverted form of line breaks. Or perhaps, a reverted form. Or an inverted form. I’m talking about the indent. Whereas line breaks in a poem creates varying breadths of white space pressing against the text’s right side (though many poems play with white space in between phrases, etc.), an indent does the same on the left side of the text in prose. It’s not as dynamic, in that it’s always the same breadth of five-ish spaces and it always arrives after a thought has been completed and before a new one begins, but it’s still a form of white space. The indent is a little gasp, a breath of air, a signal that you may pause here and go take a nap.

Prose poems differ from prose in their frequency of indentation or lack thereof. They may indent after the end of every sentence, creating one sentence paragraphs. They may indent every few sentences, creating little paragraphs. They may do both of these and create a kaleidoscope of different-sized paragraphs. Or they may indent in expected prose fashion — after the thematic train of thought of several sentences reaches its natural conclusion. Or prose poems may not indent at all, resulting in a thick square of text.

Prose poems can and should play with indentation, along with blank lines. As we saw in Bertrand’s book, every paragraph was followed by the chasm of an empty line. Prose poem writers need not be so systematic, but can insert these blank lines unexpectedly, as interruptions, as moments of suspense and hesitation, as visual evocations of poetry’s love affair with emptiness. Indeed, prose books that sniff at the edges of prose poetry (Bluets by Maggie Nelson or Essayism by Brian Dillon come to mind) are highly conscious of indentation, blank lines, and paragraph length.

ANALYSIS OF ROBERT BLY’S PROSE POEM “WARNING TO THE READER”

Let’s see a prose poem in action. A classic since 1992, here’s Robert Bly’s “Warning to the Reader”, published in The Prose Poem: An International Journal.

Immediately, we notice that Bly plops us in media res into an uncertain time and space. Temporally, we are situated “sometimes” after the point when “all the oats and wheat are gone,” and geographically, we are “standing inside” one of many “farm granaries.” Already we are experiencing a certain disorientation that doesn’t typically happen in prose. Bly quickly stabilizes us by getting us to focus on the highly specific image of “bands or strips of sunlight” “coming in through the cracks between shrunken wall boards.” The poet has trapped us inside a silo of poetic imagery. We should also note that in the very first line, Bly employs anthropomorphism with the wind sweeping the silo floor clean. It’s quite conspicuous that we’ve entered a poem, even if it’s shaped like a truncated prose piece.

The poetic indulgence continues in the second paragraph with a rhetorical question stripped of its question mark, which is technically faulty punctuation — something poets are perfectly comfortable perpetrating. The effect is a sentence that both declares and questions; it is a revelation of melancholy and wonder. I can’t find the literary term for this device (dear reader, comment if you know), but I will informally dub it the poet’s sigh. It sets off a flurry of graphic imagery of “panicky blackbirds,” which escalates in the final two paragraphs to the striking image of “a mound of feathers and a skull on the open boardwood floor.” In the final few lines, we are also treated to a slant rhyme between “days” and “glazed,” along with “skull” and “floor.” We also see carefully curated poetic diction with consonant-complementary word choices such as “gizzards” and “glazed.”

Throughout the poem, Bly builds an interesting tension between the prosaic and the poetic. For example, along with all of the above poetic elements, there are didactic lines such as, “Writers, be careful then by showing the sunlight on the walls not to promise the anxious and panicky little blackbirds a way out!” This is because, as indicated by the title, “Warning to the Reader” is a meta-poem. It’s a text aware of itself as a written thing and the reader as a critic, and it’s particularly self-conscious about its existence as a prose poem.

For example, the final line of the first paragraph declares, “So in a poem about imprisonment, one sees a little light.” This, of course, refers to the imagery of light breaking through the granary and the birds trapped inside, but it also simultaneously glances at the literal white space of the page — the “light” space — that immediately follows the word “light.” The “bands or strips of sunlight” seeping through the shrunken wall boards thus become the narrow blank spaces between lines, and the wall boards are the poem’s sentences. In short, the description of the blackbirds trapped in the granary is an extended metaphor or allegory for readers trapped in the strange structure of the prose poem.

Because Bly carefully uses polysemous language and ambiguity, the blackbirds can also be interpreted as the words themselves pummeling against the prison walls of the page margins, where normally, they would flit freely in “poems of light” — i.e. enjambed poems that glow with white space. The poet tells us that the only way out is through the rat’s hole “low to the floor”, which draws our eyes to the spaces we wouldn’t normally notice — the small gaps between lines, the vast emptiness after the final word of the poem. Bly is teaching us to be different readers in the space of the prose poem, or we won’t find any sustenance from the form; we have to both analyze the prosaic and indulge in the poetic devices to extract the content’s full meaning.

You’ll also notice that Bly pointedly identifies the trapped birds as “blackbirds.” Thus, not only do the blackbirds represent the reader and the words on the page, they also allude to one of the most famous meta-poems of all time, “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird” (1917) by Wallace Stevens. In evoking this work, Bly embeds his prose poem within the lyric tradition and establishes prose poetry as a valid form of poetry indeed.

Finally, “Warning to the Reader” concludes with the line, “They may end as a mound of feathers and a skull on the open boardwood floor.” You’ll notice that Bly pointedly chooses the word “they” for its polysemy within the text’s context. We can interpret it to mean the “Reader,” as the sentence before it would indicate, and we can also understand it to mean the blackbirds, which have been trying to get out of the granary for four days. However, its ambiguity means “they” can also be read as the poem itself; if not written or read correctly, the prose poem may end in a pile of poetic attrition — a jumble of words reduced to the reader’s skull and blackbird feathers. We are then tempted to look at the shape of Bly’s poem again, and we realize that via its meta-elements and extended metaphor, he has constructed a type of concrete poem. One last thing to note is Bly’s use of the ellipses at the end of these final two paragraphs. Not only do they visually represent the reader’s concentration trailing off, and the prose poem itself coming to an end, they serve as a kind of prose poetry line break…

All in all, the point of prose poetry can be found in the act of reading Robert Bly’s “Warning to the Reader.” He has written a clever prose poem layered with meaning and poetic devices — both of which can only be experienced by reading and rereading the text. By looking carefully at each word the poet has crafted, we are treated to a stratified experience that is different from, but still as deep as, analyzing a traditional poem. In short and quite simply, the point of prose poems is to read them in order to find meaning in the text and in existence.

CONCLUSION

Is the prose poem better than an enjambed poem? That’s for you, the reader and the writer, to decide. In terms of my own creative processes, if I’m intentionally writing poetry, I find that the prose poem is a last resort. I conceive it when the frustration of mediocre line breaks meets my desire to preserve the beautiful poetic fragments I already composed. As I unthread the lines from their shoddily enjambed form and rearrange them into a square on the page, I usually realize that this new geometry requires editing to make it complete. Or rather, fattening. A bit of blubber here and there, until I have drafted something that is still my poem, but not. It’s a prose version of my original poem.

However, if I’m intentionally writing prose with my book in mind, it always emerges as prose poems. Perhaps it’s easier for me to poeticize the prosaic than to turn the poetic into the more ordinary.

This is not to trivialize the form. Indeed, here’s a little secret: poetic prose, not poetry, is my favorite type of writing to read. And as we saw from the literary analysis of Robert Bly’s “Warning to the Reader,” prose poems can be chock-full of meaning, if only we learn to expect a different reading experience from them as compared with enjambed poems. Furthermore, as you may have caught glimpses of in the timeline, many writers have demonstrated that prose poetry is a necessary form for expressing the difficult, the ineffable, the overlooked.

Now, we’re almost done with the easy part….

Let’s figure out how prose poetry differs from flash fiction, micro-fiction, lyric essays…

5 COMMENTS

Excellent post.

Wonderful read — and here and there — very funny!

I would like your impression of James Tate’s final book of prose poems. The Government Lake.

Thanks

Excellent write and analysis!

Loved this, Hannah!