Literary Analysis

Literary Analysis

Here’s Why These 5 Creative Book Titles Work

A Brief Literary Analysis of Book Names that Resonate

Book titles beckon: from spines and covers, they yoo-hoo in froufrou fonts to prospective readers. Titles are oracles: they augur what unread pages contain. Titles identify: they turn paper piles into cohesive things, heaps into sheaves. Titles are thresholds: readers can’t enter texts without crossing the titular line. Titles frame: in minimal words, they explain what it all meant, why it was all so blue or golden or so on. Titles, though they precede, follow: texts gain names only once they’ve been written. Titles connote: they’re word clusters that conjure up paragraphs read while sick in bed on a cold winter day as the dog yipped in the yard and the world continued on in distant horns and smog. Titles can trick: bad texts sometimes bear creative book titles, and the best books can be rather brusque in their names. Above all, book titles promise: a story, a secret, a journey, a love, a moment.

Despite all this, even literary readers tend to grant a book’s title only a second’s thought before moving on to another text, or to the first page. Today, we’re going to pause and analyze, taking our time with 5 creative book titles that resonate with me for very different reasons.

Loading Mercury with a Pitchfork by Richard Brautigan

Poets purvey the most poignant imagery, and with the creative book title of this 1971 poetry collection, Richard Brautigan showcases his knack for efficiently conjuring up textures, colors, and sensations in a few words. Indeed, any one of Brautigan’s titles could be on this list. Some of my other favorites include:

- The Octopus Frontier

- In Watermelon Sugar

- The Revenge of the Lawn

- Trout Fishing in America

- Lay the Marble Tea

And so on. Brautigan’s titles are quirky, cryptic, and fuse unique images and diction. We’ll stick to looking at Loading Mercury with a Pitchfork because I find this image to be most dynamic. The word “Mercury” immediately evokes something elemental, slippery, silver, nebulous, dangerous, mythological, planetary, metallic, shape-shifting, barometric, and above all, intractable and liquid. Thus, the mere fact of “Loading” it, which suggests heavy labor and solid bulk quantities, is already a striking image. However, Brautigan teases the imagery into a philosophical commentary through the addition of a “Pitchfork” — a noun that immediately evokes something sharp, pronged, sieve-like, needle-like, manual, agricultural, methodical, devilish, and most importantly, highly unsuitable for handling an element like mercury. The title describes an action that can never be completed, a task where the only fruition is to witness a perpetual slipping away amidst continuous hard labor. Thus, the titular image, with its Sisyphean connotations, immediately declares an ongoing engagement with futility.

As with most poetry collections, the book title is derived from a poem title, and so we also get to read “Loading Mercury with a Pitchfork” within the text. Here’s the complete piece:

Loading mercury with a pitchfork

your truck is almost full. The neighbors

take a certain pride in you. They

stand around watching.”

-Richard Brautigan

Although the poem is nothing spectacular, it does showcase Brautigan’s ability to write with a distilled clarity, a deceptively simple engagement with strangely profound moments. This style is most effective in his prose, and indeed, he explains in David Meltzer’s anthology, The San Francisco Poets, “I wrote poetry for seven years to learn how to write a sentence because I really wanted to write novels and I figured that I couldn’t write a novel until I could write a sentence.”

Anyways, here, the poem coyly undermines the futility inherent in the image of loading mercury by letting the reader know that the task is actually nearly complete — by the second line, already the “truck is almost full.” Somehow, our pronged tool has been working. But the triumph of this feat of “loading mercury” is itself immediately undermined through the inactivity of the spectating neighbors: the surmounting of futility is ultimately futile because the witnesses haven’t engaged in the labor themselves, and so they can’t understand the hardship nor the victory of completing the task, but the continuation of the task depends on their viewership.

Ultimately, Brautigan has a wonderful ability to combine unexpected words to create curiously effective and concise imagery. We see this over and over in his writing, (e.g. “speed-curried bug,” “gasoline ghosts,” or “comet telegram” from the same collection), and Loading Mercury with a Pitchfork is just one example. In fact, Brautigan reminds me of Gwendolyn Brooks, who is a genius at fusing modifiers and nouns to create hyphenated/compound words, (e.g. “chipware” in place of chipped dinnerware” in “The Bean Eaters” ). But more on that in a future post.

We Should All Be Feminists by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

This creative book title by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie functions both as the book’s thesis and as a thesis for human existence in the 21st century. The book consists of one essay, which Adichie adapted from a 2012 TedTalk she gave, and runs only about 60 (small) pages. Over the course of the essay, she elaborates on the reasons why “We Should” indeed “All Be Feminists,” including personal examples of sexism’s persistence, and how although gender prescriptions constrain both men and women, they oppress women disproportionately. Adichie’s own definition of “feminist “is a man or a woman who says, yes, there’s a problem with gender as it is today and we must fix it, we must do better. All of us, women and men, must do better.”

If this seems obvious, it’s probably because you’re already a feminist, as I am. For you, Adichie’s book will likely not serve as a self-educational piece so much as an active tool that you can utilize to get people to think rationally about feminism. This is a book that’s highly portable and distributable — a text perfect for passing out, sharing, quoting, and recommending to all of those people who you suspect might not believe that “We Should All Be Feminists.” And it all starts with the titular assertion.

In terms of creative book titles, this one works because it takes a stance and declares it in a complete sentence that can be extrapolated from its home text and still carry meaning. The statement “We Should All Be Feminists” is in direct conversation with 1) the current popular misconception that feminism is no longer necessary and all the woes of sexism have been solved; 2) the long-running misconception that only women can be feminists; and 3), via the connotations of the “all,” that there is multiplicity in feminism that historically hasn’t been recognized by white female feminists.

This title is a precise pronouncement that’s designed to provoke because it’s conscious of the massive ignorance that pervades humanity’s perception of gender. Thus, I recommend that you bring this title to parties, and, being sure to give credit to the author, utilize it as a conversational springboard. I even have it on a shirt that I like to wear when walking around the conservative stronghold that is South Orange County, flouncing around in words that get such dirty looks, which makes me flounce even harder.

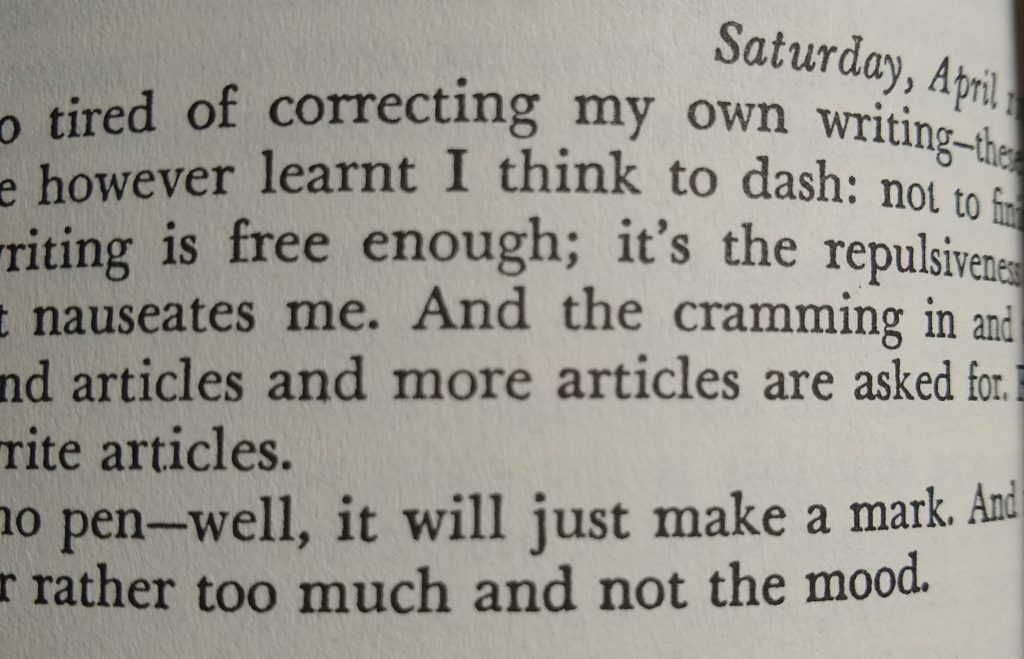

Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose

The title of Durga Chew-Bose’s book of essays (2017) utilizes a linguistic nugget found at the end of Virginia Woolf’s diary entry on April 11, 1931. Woolf was venting a frustration at catering to readers’ snipping demands, and this frustration serves as apt inspiration for Chew-Bose’s text. Frequently poetic, Too Much and Not the Mood is a contemporary fuck you to stringent form, featuring rambling essays and fragmented pieces that aren’t concerned with the bland, banal structures underpinning most new books. Although a few of the pieces are so fragmented as to feel unfinished, and the allusions to current popular figures and digital trends dilute, to a degree, the poetic epiphanies, Chew-Bose’s collection of lyric ruminations is worth a read for its strong imagery and insight into the act of writing. Indeed, any text that sticks part of a quote from Woolf on its cover is worth a read in my book.

Here’s the original entry in full from Woolf’s diary:

Oh I am so tired of correcting my own writing–these 8 articles–I have however learnt I think to dash: not to finick. I mean the writing is free enough; it’s the repulsiveness of correcting that nauseates me. And the cramming and the cutting out. And articles and more articles are asked for. Forever I could write articles. But I have no pen–well, it will just make a mark. And not much to say, or rather too much and not the mood.

-Virginia Woolf (April 11, 1931 — A Writer’s Diary)

The sentence fragment selected for Chew-Bose’s creative book title showcases Woolf’s trademark pithiness (I dare you to find a lazy phrase in any Woolf text, even her diary). Even something as simple as describing frustration becomes weighty in Woolf’s hands. The internal rhymes of “too” and “mood” acoustically bookend the title, so that the whole phrase echoes itself and reverberates in the mouth. Further, it’s fully composed of monosyllabic words, which contribute to a linguistic aura of curtness, which is compounded in the opening hammering of two stressed words, followed by the tersely lilting “and (unstressed) Not (stressed) the (unstressed) Mood (stressed).”

Although the diary entry’s gist jives with Chew-Bose’s collection’s intent, the selected quote attains different connotations when extracted and de-contextualized via placement on the cover of another author’s book. On Chew-Bose’s text, without the background of Woolf’s entry, “Too Much and Not the Mood” becomes a trenchant venting at the excess of everything. There’s simply “Too Much” in general, and the speaker’s disgruntlement is so caustic that the subject and verb are foregone completely in favor of curt dismissal. In contrast, within its original context, we realize that Woolf meant that she had “Too Much” to say — too many words — but couldn’t find the right mood to let language pour out. In terms of creative book titles, this one is an interesting demonstration of the transfigured meaning even a few words can acquire when they’re read in a different context, and of the importance of modern writers opening up dialogues across time and history by unearthing rich linguistic nuggets from past authors.

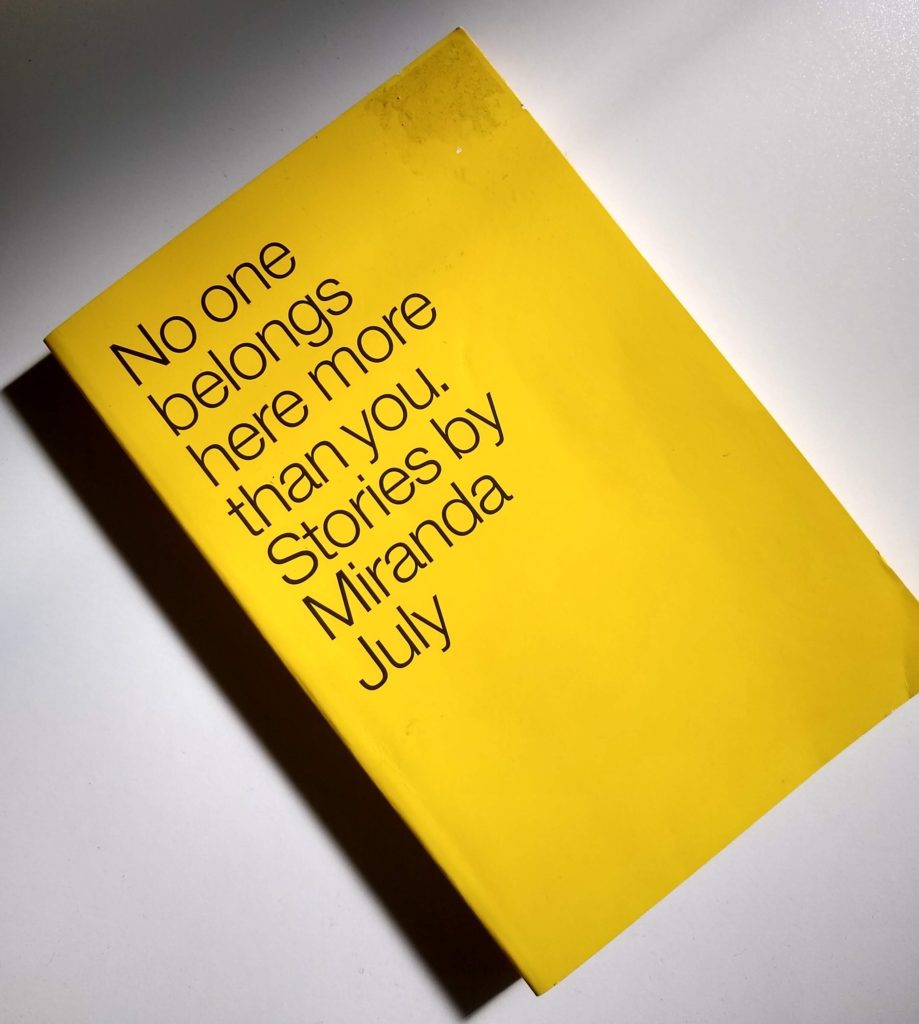

No One Belongs Here More Than You by Miranda July

Similarly monosyllabic heavy, the title of Miranda July’s short story collection (2005) speaks directly to the reader via the second person pronoun. No One Belongs Here More Than You is an authorial invitation to open the book and “belong” to the mysteries of the unread text. Indeed, as Professor Jax NTP explains, within the book, “since all of the main characters are unnamed, the ambiguity allows the reader to identify with each main character. The nebulous space that you and the characters occupy — ‘the here’ — normalizes what society uses to make the characters feel lonely.” The title is a reassuring reminder that the act of reading will be an act of joining a community, however curious it may be.

Most book names aren’t brave enough to extend, to draw attention to their length, but this one indulges in full-sentence completeness. The extension carries the reader along gently in a mini-narrative; when we read this creative book title, it’s almost as if we’ve already started reading the book, though we haven’t even cracked the first page. Further, the title declares and simultaneously defies the reader’s anxious assumption that they are an outsider, unwanted. How very strange that a piece of fiction can comfort in its ability to challenge our perpetual loneliness. How very strange and how very wonderful.

Although I’m focusing on creative book titles that resonate because of their linguistic properties, July’s also works especially well because of the cover design: there’s simply the title and “Stories by Miranda July” couched in a searingly colorful background. My personal copy is banana yellow, but other readers own dragon fruit pink, gourd orange, and avocado green versions. In all four cases, the blank space of the cover, with its absence of pictorial representation, seems to represent the space of “Here;” in other words, the cover becomes a canvas on which the reader can paint their own idea of “Here” so that they can instantly belong.

The Unbearable Lightness of Being by Milan Kundera

Here’s a secret: I haven’t read this 1984 novel by Milan Kundera. I’ve seen it on shelves and heard it described as decent reading, but have never actually dug into it. And yet — and yet, this creative book title stirs in my subconscious in moments of artistic indecision, functioning as a mantric placeholder for what will work in a space to be filled with words. Perhaps it’s because, regardless of plot, the title captures the basic melancholy of human existence: the vertigo that accompanies a self-consciousness of being tangible and insignificant. We’ve all had such moments overcome us, a long instant when we must grab the handrail because the absurdity of walking down the stairs as a fleshy, feathery self, overwhelms.

No matter the content of the novel it refers to, this title works because it offers up a universal truth. The phrase both describes and asserts, slowly lumbering into the multi-syllabic “Unbearable,” followed by a light-footed descent into the thickly lilting “Lightness of Being.” The textual fragment is paradoxically comforting in its declaration of the agony of the fact of being alive only once. When this title arises in my mind, I like to hold it and rub it like a smooth stone in my pocket, sonic salve.

Certainly, many other creative book titles out there equal or surpass the five above, and we haven’t even dug into the strange and wondrous titles that head each page in poetry collections. Sound off in the comments with the most creative book titles you can think of — and why — and stay tuned for a Part 2.

1 COMMENT

Great analysis