Discover Literature

Discover Literature

Poets, Allow Me to Reintroduce Metaphor and Simile

USE THESE FIGURES OF SPEECH TO ELEVATE YOUR CREATIVE WRITING

Romeo and Juliet. Coyote and Raven. Lucy and Ethel. There have been many dynamic duos throughout history, but none so inseparable as Metaphor and Simile, those two figures of speech that are always taught together in third grade classrooms and onward. How could any of us forget that a metaphor is when you say something is something else and a simile is when you say it with “like” or “as”?

But alas, it seems that many of our era’s best(selling) poets are content to wallow in the literal, or extend only the tippy-top of their tiniest toe into the rich waters of metaphor and simile. Perhaps it’s because they learned these figures of speech so long ago, they’ve forgotten how they function. Or perhaps it’s because readers seem equally content to shrug off the imaginative leap required to appreciate the metaphorical. Whatever the case, getting reacquainted with metaphors and similes will make us all better readers and writers, so let’s cannonball in.

SIMILE AND METAPHOR DEFINITIONS

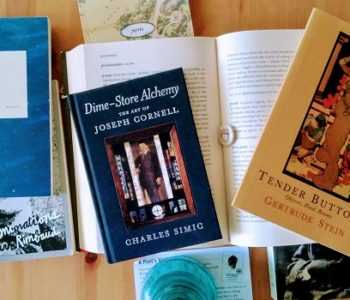

As usual, we’ll turn to Edward Hirsch for a pithy definition of metaphors:

A figure of speech is when one thing is described in terms of another — as when Whitman characterizes the grass as ‘the beautiful uncut hair of graves.’ The term metaphor derives from the Greek metaphora, which means ‘carrying from one place to another,’ and a metaphor transfers the connotations of one thing (or idea) to another. It says A equals B…”

-Edward Hirsch, A Poet’s Glossary, “Metaphor” Entry

To unpack this, we must also remember what “figures of speech” are:

The various rhetorical uses of language are considered figures of speech. These nonliteral expressions employ words in imaginative or ‘figurative’ ways.”

-Edward Hirsch, A Poet’s Glossary, “Figures of Speech” Entry

Thus, a metaphor imagines one thing as another. The statement “The oak table is wood” is not a metaphor because it describes what the table literally is. One need not make any mental leap to conceive of the oak table as wood. However, the statement, “The oak table is a wood bunker for knees during dinner,” requires the reader to imagine the table as a battlefield structure protecting lower extremities. From this arise thoughts of pea cannonballs and asparagus arrows and so on, though none of these images are explicitly stated. That’s the beauty of metaphors: they unlock exponential connotative potential in the most efficient manner possible.

However, some metaphors are so common, they no longer require the reader to make an imaginative leap and they evoke nothing. These are to be avoided. A cliche such as “he’s a rat,” is so familiar, is so instantly understood, that its non-literal meaning has become almost literal. On the opposite end of the spectrum, a metaphor that forces the reader to make too far of a mental leap is just as much of a literary no-no. For example, saying, “The oak table is a banana,” is a failed metaphor. It’s difficult to imagine a wooden table as a mushy yellow fruit; the two things’ visual, textual, and functional connotations clash with each other instead of fusing to create a new idea.

So, while metaphors equate two things, the equation only works if the two variables are literally distinct from each other, but not so unlike that an imaginative connection is impossible.

Now, a simile is simply a species of the metaphor genus. Yes, all similes are metaphors. However, as Hirsch explains, a simile is:

The explicit comparison of one thing to another, using the word as or like…The essence of simile is similitude; it is likeness and unlikeness, urging a comparison of two different things. Similes are comparable to metaphors, but the difference between them is not merely grammatical, depending on the explicit use of as or like. It is a difference in significance. Metaphor asserts an identity…by contrast, the simile is a form of analogical thinking.”

-Edward Hirsch, A Poet’s Glossary, “Simile” Entry

Do the words “like” and “as” really hold so much weight that they create noticeable nuances in the effects of these figures of speech? Why yes, yes they do. Let’s find out why.

METAPHOR VS SIMILE DIFFERENCES

Let’s begin with the two most basic ways to write a simile:

[A is like B] A butterfly wing is like a stained glass window. [A is as X as B] A butterfly wing is as kaleidoscopic as a stained glass window.

As you can see, through the word “like” or “as,” a simile holds the compared subjects at arm’s length. Two things are connected on the condition that they are not the same thing. They are the same, but different. Similes thus build contrast into their comparison. Although A is like B, although A is as X as B, A and B are still A and B: linked, but distinct entities.

You’ll also notice that the [A is as X as B] format must sprout another word in the middle to function. We’ll explore this more later in the post, but for now, observe how the general effect is a lexical stretching. Indeed, in its most compact format, a simile will necessarily be literally longer than a corresponding metaphor, even if only by one word. In the conspicuousness of their construction, similes tend to be more obviously similes than metaphors are metaphors. They identify themselves to the reader as similes.

A simile is a juxtaposition. Two things are placed side by side for the reader to compare and contrast. A simile is like the moment before a kiss, suspended in a sentence. There is breathing room and the visualizing of different lips touching, but the two individuals remain separate.

And now on to the most rudimentary way to write a metaphor:

[A is B] A butterfly wing is a stained glass window.

Metaphors bring two ideas into closer proximity to each other than do similes through the simple fact that there are less words in between those two ideas. They consolidate. A metaphor asserts that A = B. There is no difference between the two things except in order, which is significant. In a metaphor, there will always be a primary thing, and it’s not the thing that comes first in the equation — it’s the thing that that thing becomes. B is the original that accepts unto itself A. Where a distance/difference persists in metaphors, it’s in the order.

A metaphor is a synthesis. A metaphor is the exact moment the kiss happens. The gap has collapsed. The lips are touching. The breathing room becomes the same breath, and two individuals become both one and a new two.

Similes typically sound less “poetic” than metaphors, because they’re less assertive. They propose — they hold up to the light — but they do not dare to mix. For example, “I just realized your eyes are as blue as the sky,” sounds more natural in a conversation than, “I just realized your blue eyes are the sky.” A delightful breeziness fills the former. The latter will likely provoke an, “Okay poet-nerd, back off,” in everyday conversation.

Thus, similes tend to be more organic because they allow us to imagine without totally committing to the equation. A simile is a tool that helps both the poet and the reader to leap between unlike thoughts with a safety net below. A metaphor is a swan-dive off a cliff for the poet and the reader. As a result, metaphors are more dramatic and lyrical. The stakes are higher when there is no safety net. This also means there is a higher risk of a metaphor sounding “off” if the two elements are too disparate.

It’s important to note that these differences are most significant in the fomentation of the figure of speech. That is, if you generate a metaphor and then add the word “like” or “as,” the differences between the two configurations will be apparent, but not drastic. But if you’re writing a poem and you conceive of the next line as a metaphor rather than a simile, the “equation” of the metaphor will pitch the poem in a different direction than the “comparison” of the simile would have.

That is, the differences between metaphors and similes are most drastic in their contextual interactions and their spurring of your next idea. Metaphors and similes are not just literary devices; they are modes of thinking, creating, and understanding.

METAPHORICAL ORDER

Considering that a metaphor expresses an equivalence between two unlike things, what happens when we reverse the syntactical order? If, “A flame is a tame animal that turns feral in the wind,” does it also hold true that “A tame animal that turns feral in the wind is a flame”?

Clearly these are not the same assertions. Thus, although a metaphor equates, although it says that “this” is “that”, “this” and “that” are still extant as “this” and “that.” A metaphor’s power lies in the continued existence of two distinct variables forever tethered by the verb “to be.”

This doesn’t mean there aren’t metaphors that can be reversed. It simply means the meaning changes depending on what comes first. It’s up to the poet to decide which message is more powerful. In some cases, you can use this reversal to your advantage with the “callback metaphor.”

For example, at the beginning of a poem, you might wax poetic about how, “From the boat, the hard continent was a sculptor molding the ocean’s molten edge,” and after many lines filled with salt water and meaning, you might hit the reader with, “From the bluff, the ocean’s molten edge was a sculptor molding the hard continent.”

5 WAYS OF LOOKING AT SIMILES AND METAPHORS

While the difference between metaphors and similes most explicitly pivots on the words “like” and “as,” both types of figurative language can be written in various ways. Beyond the basic forms we already covered above, here are some other anatomies:

- Type: The “As If It Were” Simile

- Formula: A does X as if it were B

- Example: The car whirled as if it were a tornado

- Explanation: Similes are less linguistically efficient than metaphors. That is what makes them unique — the interjection of “like” or “as.” It’s possible to make them even less efficient, as in the above example. While condensed language is the ideal in poetry, there are exceptions where grammatical inefficiency can be used to create a desired effect, e.g. prolonging a rhythm. Keep this structure in your toolbelt, but use sparingly.

- Type: The “Comma, As” Simile

- Formula: A, X as B

- Example: The pit, dangerous as a bullet

- Explanation: Here, we snip at the first bit of gristle in a typical simile — the “is as” — and render it into a mere comma, thus changing the line’s musicality by bringing “pit” and “dangerous” closer together. This is the opposite of what we did right above. Here we made the simile more efficient, though it still can never be quite as efficient as a metaphor. The point is that there is room to play with the structure of your similes to create the best combination of sound, meaning, tone, and feeling.

- Type: The Appositive Metaphor

- Formula: A, B

- Example: The cherry pit, a bullet, must be avoided

- Explanation: Here, as an appositive phrase, the metaphor of a fruit pit as a piece of dangerous ammunition is almost a totally collapsed equation except for the offsetting commas. This is one of my favorite types of metaphorical techniques to use because a line’s sonic power isn’t hindered by “is.”

- Type: The Punctuated Metaphor

- Formula: A: B

- Example: Three ripe blueberries: soft wet jewels

- Explanation: Similarly, here punctuation is doing the equating of the metaphor through an appositive phrase. The colon is a delightful little piece of punctuation. I like to think of it as a permeable membrane that both stops the preceding thought and lets meaning osmose. It also has a mathematical feel and the sense of the metaphor as an equation will be particularly vivid with its use.

- Type: The Prepositional Metaphor

- Formula: An A of a B

- Example: A feral cat of a fire

- Explanation: Metaphors can also be expressed through prepositional phrases. Again, the benefit of constructing the metaphor in this way is primarily the sonic effect. However, also notice that changing the equation’s structure allows us to change the order of compared ideas. “The fire is a feral cat” has a meaning parallel to “a feral cat of a fire,” but the fire comes first. We can overcome the nonsensicality that arises when we invert metaphors by rewording the metaphor into a prepositional or appositive phrase. This gives us more room to play with sound combinations.

FURTHER EXPLORATIONS IN FIGURATIVE LANGUAGE

THE BLANK IS AS BLANKITY AS BLANK SIMILE

The A is as X as B simile structure that we examined at the start of this post deserves some extra exploration because it requires such a visceral knot to function. That is, it requires an extra variable to be viable: a central adjective or adverb. This is not to say that other metaphorical structures should use less. You can and should throw in a whole hunk of modifiers to create metaphors with variegated meanings, but in the “as” simile structure, a meaty middle modifier is required. This type of simile forces the poet to think about words, and that’s why I like it so much.

So let’s build a quick simile about Southern California rain using this BLANK is as BLANKITY as BLANK scaffolding:

First Southern California rain begins as softly as a TV left on.

Now that we have our skeleton, let’s poeticize the figure of speech:

First Hollywood rain begins/ as softly as a TV left on/ mute at night.

If we want to maintain the kinetic energy of this simile, later in the poem we might write:

Thunder blunders against the screen/ and lightning ignites glass like the bright white/ noise of the TV flashing over you as scenes of stallions/ gallop into shots of mountains pouring into horizons. This torrent/

In this extended simile, the experience of first rain in Hollywood, the entertainment capital of the world, is likened to the experience of watching television at night, with the metaphorical “argument” first being made through the connections between the rain’s sound and TV static, and then through the thunder and the screen, the lightning and the flashing of the TV, and the scene transitions and the increasing frenzy.

This final line is structurally distinct because it is an implied metaphor. The movement of video footage has been turned into the torrent of a thunderstorm and vice versa via the “clues” given to the reader in the preceding lines. Instead of having to say again, “This torrent of scenes that is like the rain pouring down,” the poet can expect the discerning reader to understand the metaphor suggested by the mere use of the word “torrent” after the figurative connection has been firmly made.

IMPLIED METAPHORS

More often, you’ll find that implied metaphors mention one object of comparison, but don’t explicitly state the other. For example, in a direct metaphor, we might say:

The fire was a feral cat yowling through town.

In an implied metaphor, we might say:

The feral fire yowled through town.

Feral and yowl instantly evoke angry cats, and so the words’ connotations still conjure up the metaphor without the word cat ever being uttered. Implied metaphors allow for more subtle imagery.

In terms of my own writing process, I quite literally never consciously say, I want to use an implied metaphor here, an extended one here, an appositive one here, a simile here, and so on. I compose by sound and imagery, so the metaphors crop up organically in the process of putting words together for musicality and viscerality. While poets should seek to use similes and metaphors in their writing, they shouldn’t seek to construct them according to formulas; they should harvest them as they roam their mental fields for other wildflowers (leave some for the bees to powder their fuzzy feet though).

METAPHORS AND SIMILES REVIEW

So what did we learn today?

- Metaphors bring two ideas into closer proximity to each other than do similes.

- The order of compared ideas can affect the meaning.

- Similes are more common and comforting, and evoke the rhythms of everyday speech. (If you live in Southern California, everything is, like, a simile.)

- Metaphors are more conspicuously poetic and require more commitment on the poet’s part.

- Metaphors allow for greater nuance of meaning.

- In their linguistic bufferlessness, metaphors are at higher risk of not sounding “right.”

- Metaphors and similes come in many forms and what you choose will depend on linguistic context.

1 COMMENT

Thanks for these articles, Hannah. They are improving my understanding of poetry. I took courses at a community college for poetry and in high school – both neglected to teach about concepts like the poetic shift, lineation, or image systems. I wish I had known about concepts like that years ago.