Book Review

Book Review

Ishigaki Rin’s Poetry Shines in ‘This Overflowing Light’

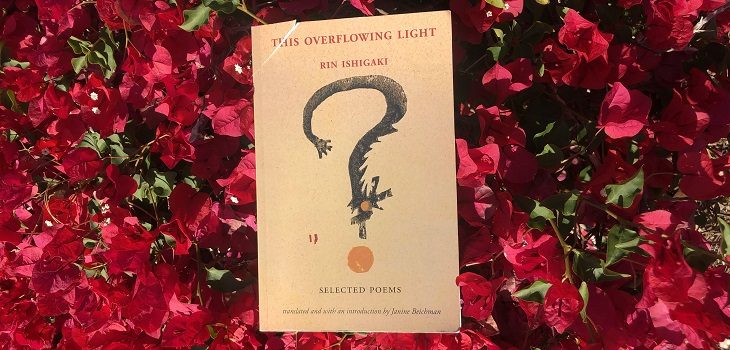

A BOOK REVIEW OF THIS OVERFLOWING LIGHT: SELECTED POEMS BY RIN ISHIGAKI (ISOBAR PRESS, 2022)

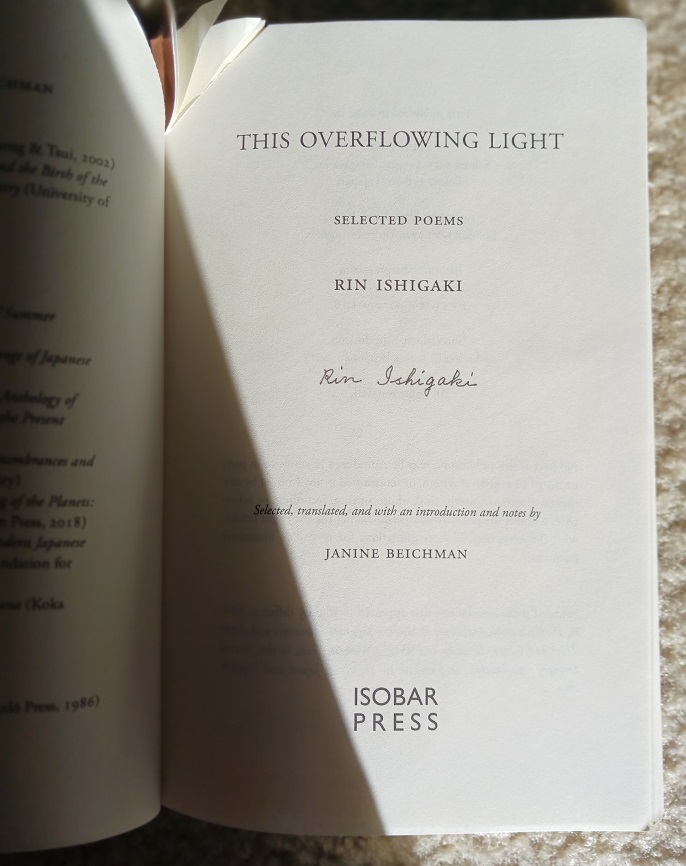

Translation tests a poem’s mettle. In the odyssey between two languages, words can grow strewed and cloudy, drifting far from their intended meaning. But in other cases, the poem may arrive filled with new music and light, and resonant with the essence of the distant poet’s voice. And what a beautiful thing that is: two poems now exist in the world, both the same and different. In the case of This Overflowing Light: Selected Poems by Rin Ishigaki, translated and with an introduction by Janine Beichman (Tokyo and London: Isobar Press, 2022), the poems have not only weathered their journey from Japanese to English, they have arrived in beautiful form. With this text, English readers now have access to fresh renderings of poems plucked from popular Japanese poet Ishigaki Rin’s (1920-2004) oeuvre, in which she confronted the routine and interpreted the uncanny as a single, working woman in post-WWII Japan.

ISHIGAKI RIN: A BRIEF BIO

In Janine Beichman’s “Introduction” to This Overflowing Light: Selected Poems, we learn that Ishigaki Rin, born in 1920, began writing at a young age, and from 1935 to 1943, published extensively in magazines specifically for girls and women (19). By this time, she had started employment at the Industrial Bank of Japan – a work-scape that would inhabit much of her poetry. After World War II’s disruption of the social, literary, and literal landscape, Ishigaki became the sole supporter of her immediate family, all of whom lived with her in a tiny house on a Tokyo back street (21). Her poems from this period writhe with the imagery of her onerous living situation in an era “between two eras” (21) – a time when the weakened family system butted heads with women’s liberation.

At the same time, the artistic landscape was blossoming through the unlikely vehicle of labor unions. Beichman notes that, “Labor union literary magazines were a prominent, though now almost forgotten, feature of the early postwar landscape,” (22) and many of Ishigaki’s poems were published in workplace periodicals by her union colleagues, and later, in scintillatingly named anthologies such as Poems by Bank Employees (1951). Thus, employment provided Ishigaki with a space to write poems — albeit often according to prescribed assignments — and a readership, such that her first poetry book in 1959 mostly contains pieces already published in bank labor union magazines.

Simultaneously, paradoxically, Ishigaki’s job restricted her to the routine of earning an income that enabled her to just barely support her family. She confronts this conflict head-on within the free space of poetry, and throughout her earlier poems, we find her grappling with different types of work: domestic, monetary, political, and creative. Eventually, Ishigaki disentangled herself from full familial responsibility when she moved into her own tiny apartment in 1970, and from the bank and union loyalties, when she retired in 1975 (26) — though ghosts of these themes rear up even in later poems.

Ishigaki lived alone until her death in 2004 (28). In addition to finally carving out her own, private living space (the boundaries of which even her friends didn’t enter) (29), Ishigaki also managed to forge out her own, public literary space — no small feat for a woman writing in the mid-20th-century. According to This Overflowing Light‘s Bibliographic Note (12), her published oeuvre during her lifetime includes her four poetry books (sampled in This Overflowing Light), three essay books (quoted from in This Overflowing Light’s Introduction), and two poetry anthologies. Her poetry texts were also reprinted in 1987-1989 as a four-volume collection, and nowadays her work can be found in multiple editions.

This tells us that since Ishigaki Rin began writing, people have wanted to read her poetry, and as we delve into the literary cross- section contained within This Overflowing Light, it’s easy to see why.

THIS OVERFLOWING LIGHT: GENERAL FORMAT

At 120 pages, This Overflowing Light: Selected Poems may feel slim, but it’s packed with the essentials of Ishigaki’s life and work. In addition to one uncollected piece, the poems it selects were extracted from her four published books of poetry:

- Watashi no mae ni aru nabe to okama to moeru hi to (Before me the Soup Pot the Rice Pot and the Bright Burning Flame) (1959)

- Hyōsatsu nado (Nameplates and More) (1968)

- Ryakureki (My Life in Brief) 1979

- Yasashii Kotoba (Tender Words) 1984

The book runs chronologically, with seventeen poems selected from Ishigaki’s first book, fourteen from her second book, ten from her third, one from her fourth, and finally the one uncollected poem. Thus, the choices are weighted towards Ishigaki’s earlier published writing.

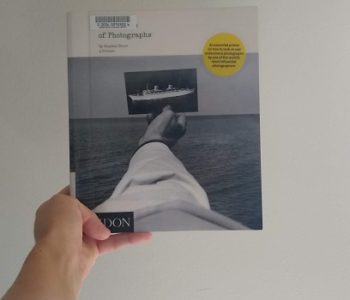

(Ignore the cover damage that happened during shipping from Amazon.)

The guardian of This Overflowing Light is translator Janine Beichman — the winner of the 2019-2020 Japan-United States Friendship Commission Prize for the Translation of Japanese Literature — and we are in good hands. The front matter includes Beichman’s approximately 25-page “Introduction,” which contextualizes Ishigaki’s poetry with biographical elements, careful analysis, insight from the poet via her prose writings, and the familiarity of someone who interviewed Ishigaki, “in 1998 over coffee at the Tokyo Station Hotel, one of her favorite haunts” (29). It’s clear that the translator has a close understanding of Ishigaki’s significance in Japanese literature, and she’s able to deftly oscillate between a macro and micro view of her subject’s work while still allowing the poet to speak for herself.

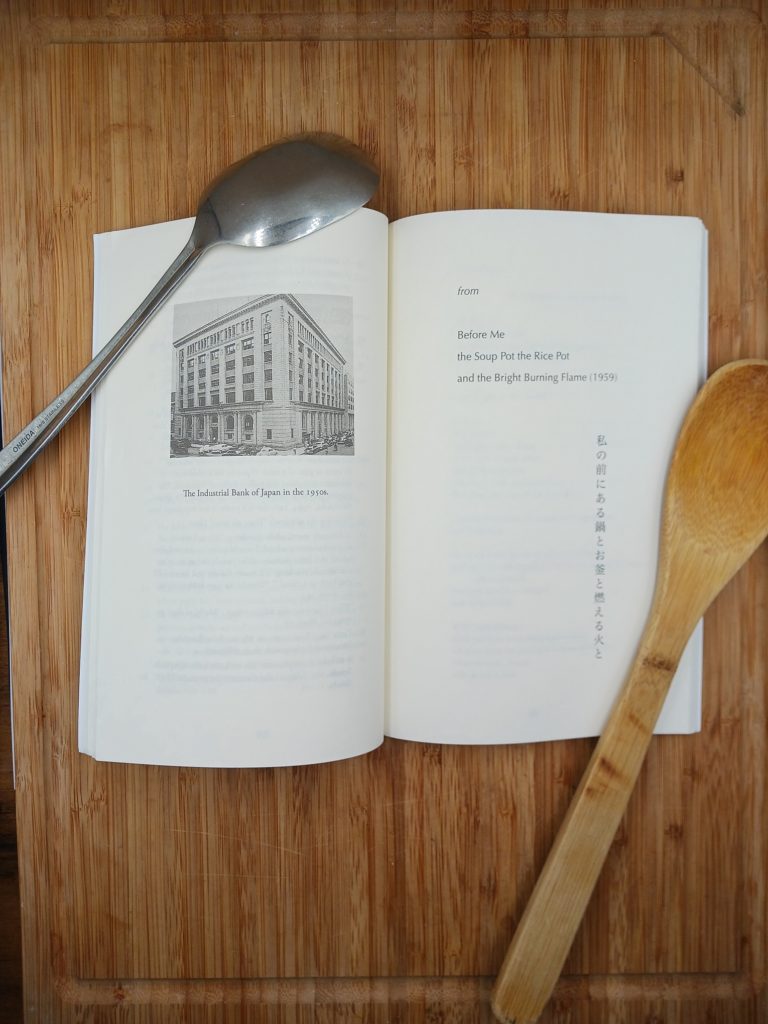

Photographs intersperse This Overflowing Light – Ishigaki at various ages, along with a snapshot of the Industrial Bank of Japan in the 1950s. There are also facsimiles of two of Ishigaki’s original poem manuscripts, along with one of her handwritten signature, “which is in the collection of the translator” (10). These small artifacts elevate This Overflowing Light from a mere volume of Selected Poems into a sort of archive that has gathered the most illuminating pieces of Ishigaki’s literary presence for readers both familiar and unfamiliar with her work to appreciate.

Beyond this, the text manages to be efficiently informative. Each section includes the title of the published poetry volume in both English and Japanese. The back matter includes “Notes to the Poems” and the “Original Poem Titles.” The former provides extra context, along with occasional analysis, while the latter enhances the reading experience even for the non-Japanese-fluent reader. For example, it’s interesting to confirm that “0” is still “0” in its original language. Overall, This Overflowing Light is a concentrated dose of poetry that’s just plain good reading, and also a tribute to Ishigaki Rin’s life.

FROM: BEFORE ME THE SOUP POT THE RICE POT AND THE BRIGHT BURNING FLAME (1959)

The title of Ishigaki’s first poetry volume is fantastically poetic. It’s long, fragmentary, punctuation-less, and traces the states of matter – liquid, solid, gas. This blending of the earthly with the ethereal embodies the overall tone of her first published book. She’s equally comfortable honing in on something as specific as an envelope, as she is on something as nebulous as motherhood.

We can see this right off the bat in the opening poem, “Greetings” (43). This was “her first poem that gained widespread attention,” (Intro – 24), and was commissioned by the secretariat of her bank’s labor union to mark the anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima. In one hour, Ishigaki produced what is technically an ekphrastic poem based on a “photograph of the atomic bombing” (43). “Greetings” begins with the hyper-focused image of “Oh, this face/so horribly burned,” which then gets contrasted with the speaker’s, spectators’, and readers’, “today’s healthy faces/morning’s fresh and open faces.” Using repetition and juxtaposition, the poem easily weaves from the past to the present, from the present to the absent, and from the solid to the ominous.

ISHIGAKI RIN’S PALPABLE IMAGERY

In Before Me the Soup Pot the Rice Pot and the Bright Burning Flame, Ishigaki Rin expertly depicts the world in simple, yet palpable words. Images reappear throughout the text — apples, balloons, a tin roof — as she returns to the familiar to consider it from a different angle. Such multiplicity of meaning extracted from such ordinary objects is the sign of a master poet.

We see Ishigaki’s imagery hard at work in the book’s textured, titular poem, “Before Me the Soup Pot the Rice Pot and the Bright Burning Flame” (48), which tackles how domestic tasks maintain female oppression. She traces a matriarchal lineage that religiously cooked for their families, pouring their “love and faith” into the vessels of “soup pots” and “rice pots,” and creating “plump/moist grains of lustrous rice,” “red carrots,” “black kelp,” and “meat and potatoes.” She invites women to instead study in order to “provide sustenance for human beings.”

In writing this poem, Ishigaki does as she advises: she pours herself into the vessel of the page and gifts readers with fresh imagery of nourishing morsels. As a result, she both celebrates and liberates herself from the kitchen-centric lineage she’s describing, such that the “bright burning flame” morphs from fuel for cooking to the burning desire to create art.

This Overflowing Light succeeds at selecting poems that are in immediate conversation with each other. For example, from the aforementioned food-centric piece, we flip the page to “The Women’s Bath” (50), which opens with the delightfully grotesque scene of, “piping hot clouds of steam blanket the public bath/the crowd bobbing and bumping like potatoes/washed in a barrel.” It’s almost as if the women have metamorphized into the food they had to cook in the previous poem. “The Women’s Bath,” like nearly every poem in this collection, is chock-full of strong verbs and sensory imagery: “pepper-and-salt perm,” “washed hair seal-slick,” “seaweedy wisps,” and “brews a sudsy foam.” Ishigaki’s diction, filtered through Beichman’s careful translation, withstands the decades and surprises even through re-readings.

THESE SILENCES, THESE ABSENCES

Beyond great imagery and word choices, Ishigaki excels at aposiopesis: the literary device of suddenly breaking off in speech. She ends her lines at the perfect moment – on the breath right before the secret is given away. These silences, these absences, these insinuations, are the work of a professor: Ishigaki is subtly teaching the reader how to write poetry. She gives us enough details to imagine, but not so many that we’re overwhelmed. As a result, each reader generates a different ending as they silently fill in the final blank. That’s the beauty of leaving one word unspoken, of ending on a hyphen such as in “There Is In This World” (52): “I go, I go, I go and yet – ”, or an ellipses in “The Watcher” (53): “Who is the watcher…”. Thanks to Ishigaki, we act not just as a reader, but as the poet.

The lack of full stops throughout these translations of Ishigaki’s writing compounds this feeling of the unsaid. In her “Notes,” Beichman explains that, “In these translations I have adhered to Ishigaki’s somewhat idiosyncratic punctuation as closely as possible because it is intentional on her part and her guide for the reader” (111). Indeed, in these versions of Ishigaki’s poems, the only time sentences come to a stop is at question marks, which aren’t really endings, but rather the beginnings of ideas.

Perhaps this shying away from an irrefutable conclusion is because Ishigaki so often grapples with the everyday nature of mortality, such as in “Poverty” (59), and “Getting Ready” (62). In the absence of full stops, the poems become almost immortal, and transcend the end of the poet’s time.

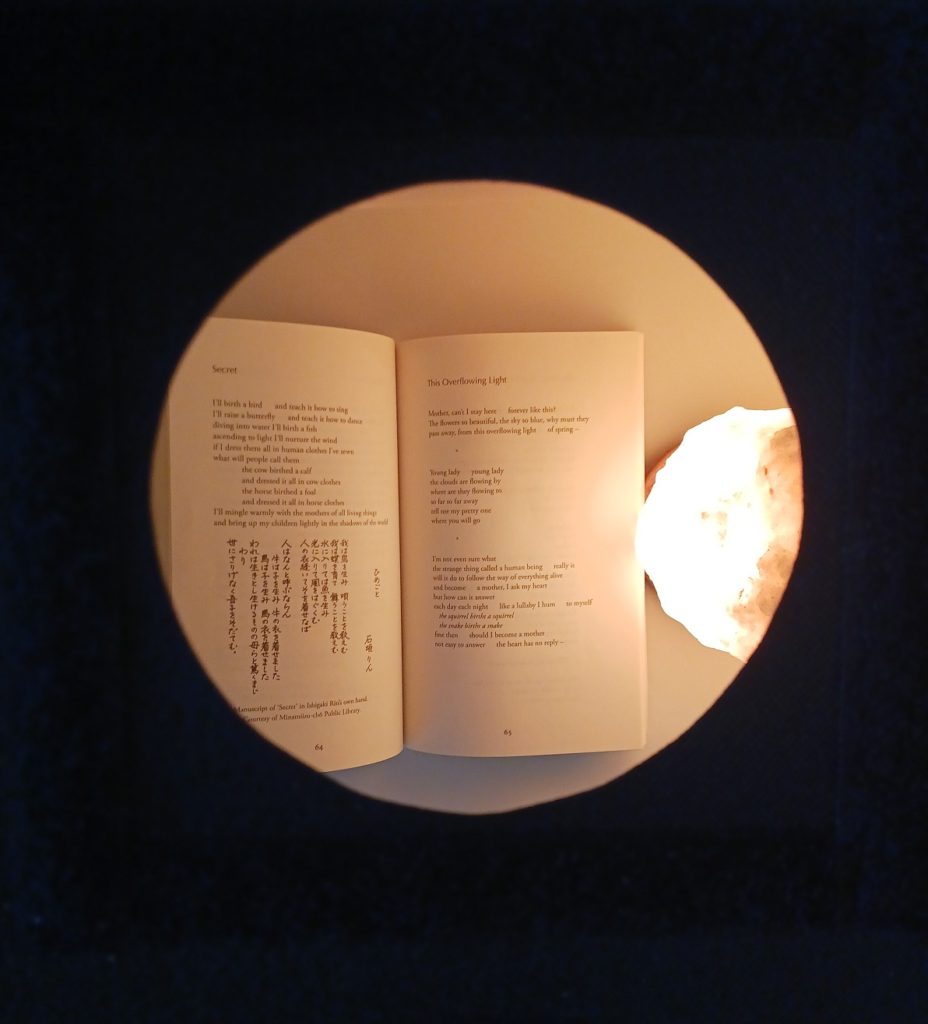

Though Ishigaki’s poems frequently express anxiety about death, her writing writhes with life. It’s full of living, as we see in the final stanza of the book’s titular poem, “This Overflowing Light” (65):

the squirrel births a squirrel

the snake births a snake

fine then should I become a mother

not easy to answer the heart has no reply –

The literal answer, of course, can be found in Ishigaki’s biography – she chooses not to have children. But in her literary wondering, in her lyric mulling through the possibility, she does end up creating. As the snake births a snake, so the poet births poetry, or perhaps, the poet births light.

FROM: NAMEPLATES AND MORE (1968)

THE FREE SPACE OF POETRY

The next fourteen poems in This Overflowing Light were extracted from Ishigaki’s 1968 text, Nameplates and More. This sampling opens with the poem “Little Clams” (69), along with a facsimile of Ishigaki Rin’s manuscript for it (68) on genkō yōshi (manuscript paper).

In any language, a poem’s original manuscript will be a different poem than its future typographical reproductions. That’s because poetry plays with white space, as we learned in the poetic line breaks guide. A poem is a visual piece of art crafted from marks and emptiness, and the emptiness morphs based on the page. Moreover, the poet’s hand cannot avoid the quirks of the poet’s brain. We might write a word so much, it slips out of us like a breath, a gasp, such that others must puzzle over that dang scribble. The hurrying of the line, the pressure of the poem, the rushing to the ending – it’s all recorded in a poet’s handwriting. Thus, fonts tame poems, usually necessarily.

In Ishigaki’s “Little Clams” manuscript, we get to see her characters frequently press up against the boundaries of the genkō yōshi squares, defying the grid, and revealing that the momentum of good poetry is always visible and universal.

In her prose quoted in the “Introduction” to This Overflowing Light’s, Ishigaki writes that, “The home was bondage, the workplace subservience…There was only one thing I did because I wanted to do it, a space where I could do as I pleased, and that was poetry” (28). This concept of the act of writing poetry as a free “space” distinct from physical space is replicated in each poem written on the free space of the page. Some published poets unfortunately only pay attention to their words, but Ishigaki understands that the space in/on which her words appear is just as important, and this is in turn understood and tended to by the translator, Janine Beichman.

EMBRACING THE ANIMAL

“Little Clams” (69) contains the fantastically morbid image of the poet waking up and finding “the little clams I’d bought that evening/were alive mouths open.” By the end of the poem, she has determined, “After that couldn’t help it had to/sleep all night with mouth ajar.” In this wonderful reversal, the speaker must mimic the clams in order to feel alive, and in doing so, surrenders herself to the same death the clams inevitably face when they’re consumed in the morning.

Here again, we see Ishigaki grappling with mortality via food, though in this nearly decade-later volume, the surreal infiltrates a little further. These motifs turn up again in “Nursery Rhyme” (85), when Ishigaki compares the white cloth laid on her father’s dead body to the “white tea towel that’s laid/on the food cooked for dinner” (85). The speaker then determines that when it’s her turn to die:

....I’ll be like a gorgeous restaurant meal beneath the white cloth Fish and chickens and wild beasts have such a yummy yummy way of dying.

The feral – animal – carnivorous – hungry voice that overwhelms the poem’s end with its desire to survive, ironically confirms the speaker’s certain future death. In other words, giving in to our mammalian urge to live also means accepting our ability to die. This juxtaposition that slyly manages to fuse, separate, and subvert all at once exemplifies one of the most enjoyable techniques Ishigaki uses in her writing.

WHAT REMAINS UNSAID

Though many of the pieces in Nameplates and More move with Ishigaki’s familiar lyric-prosaic flow, in others, such as the above, her syntax is more abrupt. Still, she continues to delight in trailing off and multiplying meaning through aposiopesis. For example, in “Flowers” (73), the first line ends with ellipses, leading us into the almost psychedelic imagery of “huge chrysanthemums stirring,” only to release us into “…at the hush of that crush” in the last line, which in turn releases us into the void of the page.

This volume’s title, Nameplates and More, gives away which poem of this batch was Ishigaki’s most popular. Despite this, all of the selected poems from her second collection are quite good. For example, in “Rakugo” (76), we are treated to vibrant alliteration/consonance in lines like, “take this thick rope called kith and kin,” and imagery such as, “little red bean-drops of blood.” In Beichman’s translation of “Cliff” (75), we find Ishigaki playing with space again, but this time between words, in the portmanteau of “oneafteranother.” This lovely, melancholy piece, which grapples with civilian suicides after Japan was defeated in WWII (113-114), is even more fragmented than her previous work. Here, Ishigaki demonstrates that the more the poet leaves unsaid, the greater the possibility – as long as you can reveal that possibility with careful lines such as:

And guess what not one of them has reached the water yet It’s been fifteen years what’s going on There, that woman

Note how the line lengths and breaks mimic the literal action of the poem. The line that declares they haven’t reached the water yet stretches out as far as it can go, like both the titular “Cliff” and the women’s fifteen-year descent to the water. Throughout this final stanza, the poem attempts to save the women by interrupting its own sentences, by turning to aposiopesis, by listening to itself and learning the importance of silences. Thus, the last two lines act as a witness to the lone word/figure of a “woman,” and direct our eyes to her just as she’s on the brink, while ultimately allowing her to hover in the blank space of the page/possibility by leaving the action unspoken.

FROM: MY LIFE IN BRIEF (1979), TENDER WORDS (1984), AND UNCOLLECTED

MY LIFE IN BRIEF

The ten poems selected from Ishigaki Rin’s third volume of poetry, My Life in Brief, feel slightly more settled than the aposiopetic bucking of her younger pieces. As the title suggests, the poet adopts a retrospective view in this volume, frequently in relation to the government.

For example, she bookends the poem “My Life in Brief” (94) with the politically-tinted statements, “I was born in a part of town that had a regimental headquarters” and “I grew old in a part of town that had an Imperial palace.” In “Woman” (99), she laments “what a fool I was” for having faith in the public sector. And at other moments, the past intrudes upon the present in these selected poems with striking clarity. A visit to a crematory in “Tree” (95) is interrupted by the couplet, “Forty years ago when she was four my little/sister turned to ashes in the same oven.”

Ultimately, however, the poems from My Life in Brief reverberate with Ishigaki Rin’s distinct poetic voice found throughout her writing. We find gritty imagery of cooking and food, head-on confrontations with death, work and post-war landscapes, almost psychedelic interactions with nature, strategic line breaks, and the wisdom of a woman who has had to wade through years of home and public labor.

TENDER WORDS

This Overflowing Light only contains one poem for 1984’s Tender Words, entitled “Sweetfish.” This leads me to my only critique about this book: I wanted more. It would have been a joy to read another dozen poems from Ishigaki’s last published volume, and including more of her later work would give the reader a better sense of her thematic development over time. Still, despite this, This Overflowing Light: Selected Poems feels complete. Any reader who hasn’t read Ishigaki Rin yet should start with this intimate collection, because her voice rises up through every page, translating the everyday and the fantastic into poetry that will both shock and comfort you.

UNCOLLECTED

The fact that This Overflowing Light begins with the poem “Greetings” and concludes with the uncollected piece “Good Night” (106), should give some sense of how thoughtfully this book was compiled. In this final poem, which was commissioned by Tokai Television Broadcasting in 1980 for its sign-off each night (115), Ishigaki tucks us into bed with revealing truths such as:

From the day we were born we have practiced how to sleep Even so we can't always do it well

Gaps like the one you see in the first quoted line permeate the whole poem, as if caesuras have been given their own space to speak silently on the page. The result of these pauses, in conjunction with close, cozy word choices such as “damp, sinking,” and “how tenderly, how warmly,” is a poem that mimics the sensation of drifting off to sleep. And how lucky we are to have Ishigaki Rin narrating the story of our slumber.

THE TRANSLATIONS IN THIS OVERFLOWING LIGHT

Experienced only in English, the translations in This Overflowing Light read smoothly, they maintain a consistent, authentic voice across the book, and most importantly, they sound like real good poetry. As non-kanji-kana-literate, I can’t comment on their relationship to the original, but I thought it might be interesting to briefly compare Beichman’s translation of “Little Clams,” which we looked at earlier, with the same poem translated as “Clams” by Hiroaki Sato [found in The Penguin book of Women Poets (1979)].

While Beichman translates the first line as “Woke up in the dead of night,” Sato presents it as, “At midnight I awoke.” The word choice of “dead’ in Beichman’s version foreshadows the events to come in the poem, and is more in tune with the piece’s overall mortality theme; it holds more weight. Similarly, in the second stanza, Beichman chooses the better-sounding “gobble,” while Sato chooses the more passive “eat,” and in the final stanza, Beichman chooses “cackle,” versus Sato’s more predictable “laughed.” Overall, Beichman’s diction feels more unique and active than Sato’s more familiar translated word choices.

Beichman also includes much less punctuation, which leads to greater syntactical nuance, which in turn allows for greater multiplicity of meaning and emotion. For example, while she translates the final few lines as “After that couldn’t help it had to/sleep all night with mouth ajar,” Sato writes them as, “After that/I could only sleep through the night,/my mouth slightly open.” Beichman’s run-on version feels more natural, and contains a greater sense of urgency than Sato’s more formal presentation. Translation is the art of interpretation, and overall, it feels like Beichman has interpreted Ishigaki Rin’s poetry in a fresh, nuanced way in This Overflowing Light.

THIS OVERFLOWING LIGHT BY RIN ISHIGAKI: IN CONCLUSION

Attention to detail defines Isobar Press’s 2022 edition of Ishigaki Rin’s work. It’s a concentrated dose of poetry that honors Ishigaki’s oeuvre and unique voice with biographical material and thoughtful translations. As standalone pieces, the selected poems are fantastic, and as a whole, the collection serves as an important resource and introduction to Ishigaki Rin’s poetry for English readers. It captures the essence of a poet who can cast a light on her time while still reading as timeless 60-odd years later. I’d highly recommend This Overflowing Light to anyone who appreciates good poetry, which should be everyone.

3 COMMENTS

Very grateful for myself (the translator) and Ishigaki and Isobar (Paul Rossiter) to have had this book read so thoroughly and so thoughtfully. I learned many new things about the poems from your perceptive readings and about Ishigaki’s work itself, as well as the word ‘aposiopesis.” Thank you.

Excellent review. Looking forward to reading these poems.

Your own use of language is uplifting and a pleasure to read on . . . and read more. Thank you. And thank you for your use of photos and ultimately, Rin Ishigaki.