Book Review

Book Review

‘On Color’ and ‘The Music of Color’ Book Reviews

A DOUBLE-DECKER BOOK REVIEW OF ON COLOR BY DAVID SCOTT KASTAN AND STEPHEN FARTHING (2018), AND THE MUSIC OF COLOR BY SHIMURA FUKUMI (2019) – TWO NONFICTION TEXTS EXPLORING COLOR

From the new books at the college library where I work, I plucked The Music of Color by Shimura Fukumi, enchanted by the cover photo of blue, white, and green yarn, the soft and creamy dust-jacket, the poetic title, and the dazzling photographs nestled amid lyrical text within. Then I put it in my desk drawer where it sat like a glowing orb while I did actual work.

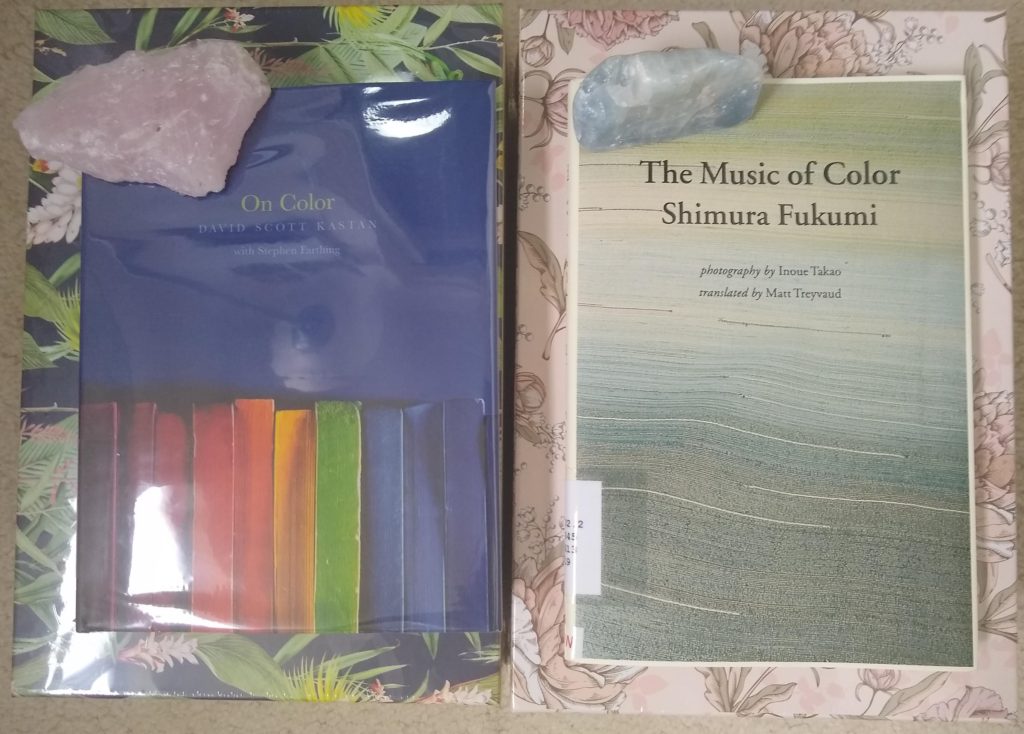

Over the next few days, more new books were sent out to the shelves and, being a greedy reader who wants all the freshest volumes, I also harvested On Color by David Scott Kastan with Stephen Farthing, wooed by its squat shape, its indigo cover depicting a chalk stick rainbow, its vivid pictures, and its promise to investigate the intriguing subject of color.

Sensing that I had too many books waiting to be read (I forgot to mention there were sixteen other ones in my drawer), I vowed to start reading right then, starting with Kastan and Farthing’s text. When I finished it the next day, I pulled out my next selection — The Music of Color — and realized that it was serendipitously also about color. Here’s a double-decker book review to celebrate the thematic coincidence, though one of the below texts is less than deserving of a party.

Book Review of On Color by David Scott Kastan and Stephen Farthing

This apparently neat little book is written by David Scott Kastan, an English professor at Yale University. Oh yeah, and Stephen Farthing, an artist and emeritus fellow of St. Edmund Hall at Oxford University, apparently had a hand in it too — though certainly less than Kastan, whose name glowers over Farthing’s on the cover. The Preface clarifies that the text is a collaboration, and although Kastan did the writing, its inspiration, content, and chapter focuses were born from conversations between the two men.

The Introduction then reveals that “the book’s structure is neither thematic nor chronological. It is topical (in several senses of the word) and opportunistic…Each chapter uses its nominal focus on a single color to explore some discrete aspect of what makes the subject of color as compelling as color is itself” (16-17). Thus, from the get-go, the book establishes that it really has no plan — and it only gets messier when read.

Not that every text needs to be rigorously structured. However, rather than massage out the poetry that thrives in unclassifiable forms, Kastan (with Farthing), over and over try to pile their subject into flimsy boxes that simply taint the colors — and that still don’t keep this unruly, aqueous subject from running all of the place.

Chapter 1, “Roses are Red,” quite literally says nothing about the color red. Instead, it uses “red” as a placeholder for thinking about the concept of color as a phenomenon dependent on the observer. This is a chapter about the theory of color — and a poorly articulated theory at that. For example, Kastan writes that “Color is…well what? Color, we might say, is a particular aspect of an object’s appearance. What aspect? Unfortunately, its color is what we are tempted to answer. And that’s the problem. With color we always seem to get trapped in circularity, and it is hard to figure out how to escape it. Still, we should try. So we need to start again, this time by trying to figure out why red things look red, or, to be more precise, why, for normally sighted viewers in normal lighting conditions, red things look red…The obvious answer, ‘Because they are red,’ is simple and intuitive (and secretly what all of us think). But it avoids the question. And it isn’t, in any case, true” (26).

JESUS CHRIST, GET TO THE POINT. Mind you, this quote comes after two pages of the exact same waffling and meandering, followed by two more pages of circuitous assertions. It feels like Kastan can’t quite wrap his head around the concept, and so must repeat himself and spell it out within the text, instead of presenting the information with lucidity marinated outside of the composition process. And then, even worse, he just moves on. He establishes that “color must be seen” (30) and then fades out with an easy, “But we do see it, so we know that it exists. We see it, and that is part of the process by which it comes into existence. We see it, and maybe there isn’t much more to say about it — or any more that we need to say” (30-31). First the color red gets shrouded in theory, and then the theory gets shrouded in unanswered questions and prosaic fluff.

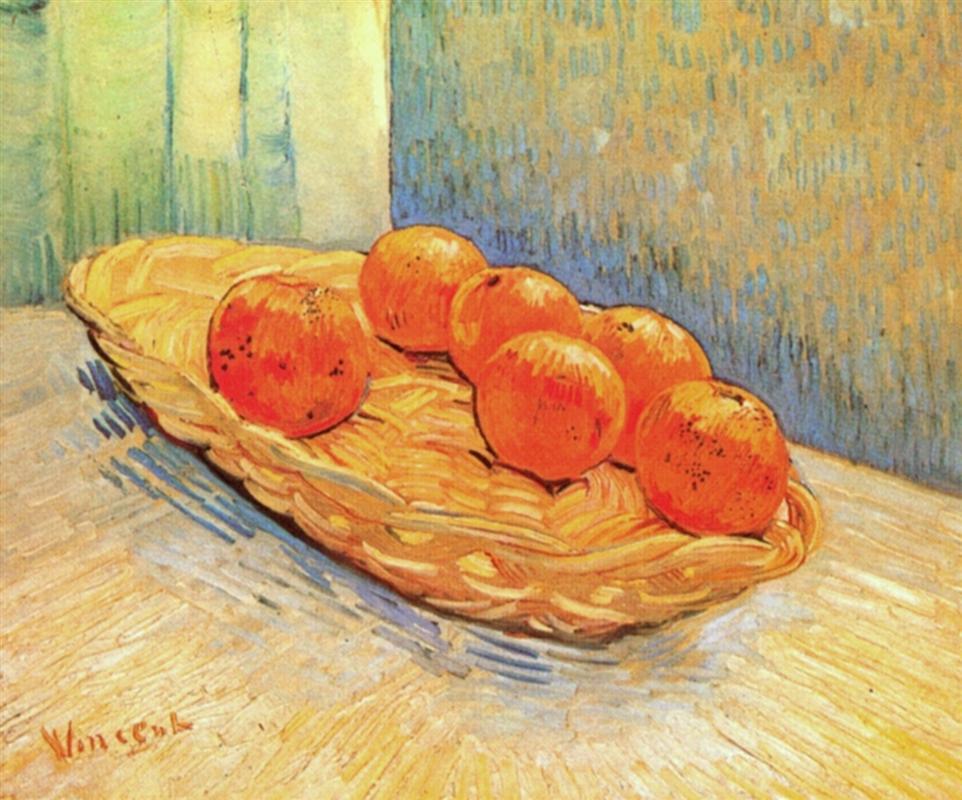

Thankfully, Chapter 2, “Orange is the New Brown,” is better. Although it gets off to a slogging start describing how the word for the color orange didn’t exist in English until the oranges were brought to Europe, it eventually moves into an analysis of Van Gogh’s 1888 oil painting, “Still Life with Basket and Six Oranges.” Here, it seems, is where Farthing comes in, and indeed, the greatest moments of insight throughout this book involve art, which would indicate Farthing’s hand. Although the analysis is still woven into Kastan’s periphrastic writing, we get such nuggets as “the modest kitchen scene is energized by the six balls of glowing orange sitting in the oval willow basket on a table” and “they are made not by coloring in the outlines of the six oranges but by allowing the orange color a life curiously independent of the fruit whose name it bears” (50), along with (in a comparison with Luis Egidio Melendez’s “Still Life with Oranges and Walnuts”) “the essential difference between the two paintings is that Melendez represents objects so as to conceal the fact that they are made of paint; Van Gogh represents objects as an opportunity to explore and extol what paint can do. Melendez paints volume; Van Gogh paints color. Melendez is painting oranges; Van Gogh is painting orange” (51).

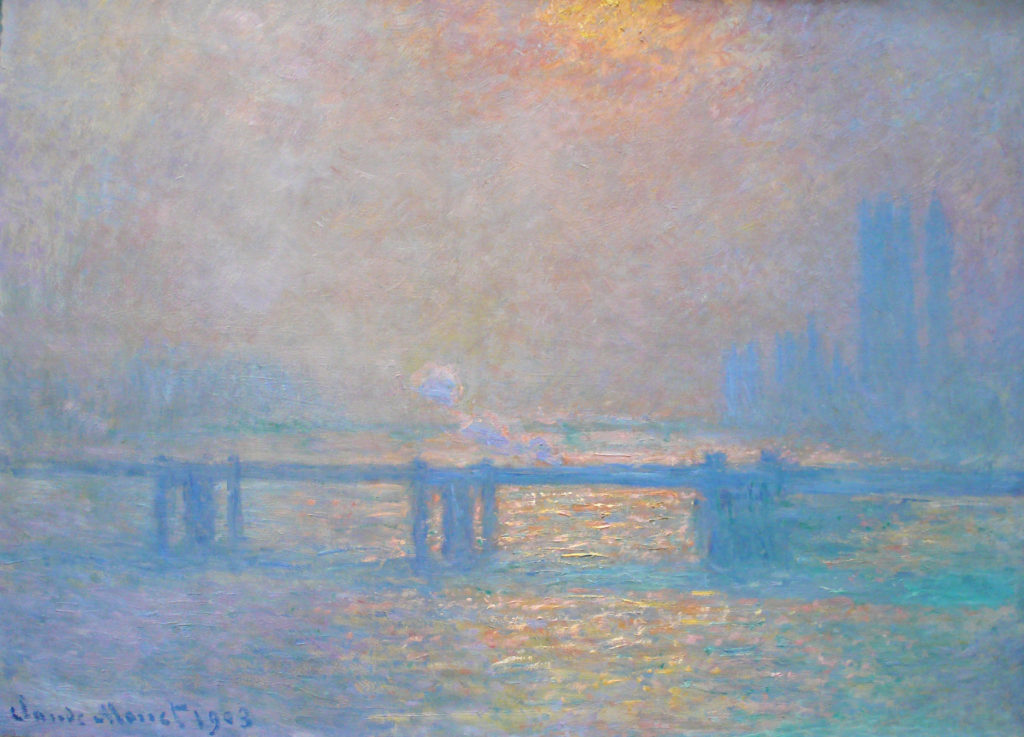

A similarly successful chapter is Chapter 7, “At the Violet Hour,” which digs into the Impressionist movement and the artists’ ubiquitous use of the color violet. Although this chapter similarly begins with un-insightful word origin tales, it progresses into such gems as “they [the Impressionists] were committed to neither optics nor objectivity. Rather, they were painting something in between. Literally. It isn’t that they painted objects as we see them. They painted the luminous air and light that exists in between the eye and those objects…And surprisingly, the in-between seemed to have a characteristic color. ‘I have finally discovered the true color of the atmosphere,’ Manet would crow near the end of his life: ‘It is violet'” (145-46). Here, the poetry of the color violet — while perhaps not infused with lyricism — at least isn’t stripped of its vibrancy by the lens through which its being presented. Considering violet within the context of Impressionism, On Color actually taught me something about the hue and infused it with a new energy I hadn’t sensed before.

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said of most of the other chapters. Chapter 3, “Yellow Perils,” approaches the color yellow through a racial lens by examining how “Asians clearly but not inevitably became yellow” (69) in the eyes of “Westerners,” and then moves into a discussion of skin color through the vehicles of Byron Kim’s and Glenn Ligon’s visual art. While, once again, the artistic analysis is interesting, the chapter fails as a whole in its initial insistence on considering skin color from a strictly European historical viewpoint. Kastan’s entire analysis of the disturbing fact that “Chinese and other East Asians had slowly but unmistakably become yellow in the Western imagination” (64) relies solely on European narratives. Once again, the white oppressor is granted a louder voice than the oppressed. The authors seem to try to balance this by including Byron Kim’s contemporary visual commentary on skin color, Synecdoche, but why not ALSO subvert the traditional historical narrative by turning to the viewpoint of those who suffered the oppression, rather than the oppressors? As a professor at Yale University, Kastan surely had access to a plethora of resources that would have allowed him to frame this chapter very differently.

Something even stinkier happens in Chapter Six, “Dy(e)ing for Indigo.” This section springboards from a (once-again) European awakening to the existence and allure of indigo, a “dye [that] had been known and used for thousands of years” (124) outside of European culture, to an examination of the slave labor used to cultivate indigo in “Western” society. While it is indeed important to investigate this, the authors attempt to support their thesis by (once-again) granting space to racist texts in the name of their historical specificity.

In particular, Kastan and Farthing extensively refer to Bernard Romans’s Concise History of East and West Florida (1775), which details the slave labor and process used to cultivate indigo while also wholeheartedly praising the use of enslaved Africans. The authors of On Color attempt to qualify his work with statements like “on the topic of the local indigenous populations he is even worse” (128), but then proceed to argue that “There is something shocking in reading Romans today, especially the blatant and unapologetic racism that irrupts from the pages of remarkably alert and detailed observations of natural history. But arguably this is preferable to the many other early accounts of indigo cultivation in which passive verbs erase the reality of the labor altogether” (129). Really? “Remarkably alert” and “preferable”? REALLY!? How about neither is preferable, and shouldn’t we be questioning the alertness of a man who didn’t even comprehend the horror of forcibly transplanting and violently exploiting human beings?

Kastan and Farthing then contrast Romans’s work with a “seventeenth-century French engraving” that they argue embodies the fact that “indigo cultivation seemed to encourage idealization” (130). From this visual and written pairing, they deduce that “Romans, even in his overt racism, is so much more honest than the engraver” (132). Say what? There’s a disturbing sense of the authors repeatedly attempting to redeem Romans in order to utilize his narrative. In short, Kastan and Farthing keep trying to polish the worst turd, and they end up with shit all over their pages.

Not only are most of the sources and perspective are all too familiarly white (and male) throughout On Color, some chapters are curiously blanched of any color, like vegetables boiled too long, or maybe, like the authors didn’t even realize there were vegetables in the pot and instead decided to focus on the boiling water.

Chapter 4, “Mixed Greens,” is an especially egregious stripping of color’s vibrancy. And it’s not just because green is my favorite color: the chapter is a bizarre, incredibly boring list of hues in a political context. Here’s a sample: “Brown has been the color of facism, though, somewhat confusingly, black is the color of the Greek facist party called Golden Dawn. In 1986 in the Philippines, a Yellow Revolution drove Ferdinand Marcos from power by massive popular protests, during which yellow flags and ribbons served as the sign of solidarity” (94). The rest of the section drones on exactly like this, providing surface level facts about the variegated colors of politics, and rarely actually talking about green. Of all the ways that green could be ruminated on — the magic of chlorophyll, oak trunks as emerald moss canvases, dragonfly abdomens, rainforest butterflies, just-dropped acorns, evergreen trees seen through haze, aurora borealis, and more, and On Color chooses “green” political parties. And by this I mean that’s all the book does: the chapter’s loose thesis is that environmental groups use green, though they could also use blue. Very astute David and Stephen, very astute.

Overall, except for its visual arts commentary, On Color by David Kastan with Stephen Farthing is strikingly colorless. Chapters begin with uninteresting objects and historical facts, and then ramble into some more dull objects and historical facts that create such a vast distance between the color in question and me as the reader that I often found myself trying to remember what color chapter I was in. Perhaps what this book reveals most acutely (and unintentionally) is that certain elements of our world lose their vibrancy when they’re throttled by academic thought (though Kastan’s prose frequently feels less-than-academic — dare I say, juvenile). The best part about this book — and the only colorful part — was the literal color of the cover and the end papers.

ISBN of Edition Read: 9780300171877

Notes of Oak Literary Blog Book Review Score for: On Color by David Scott Kastan with Stephen Farthing

3/10

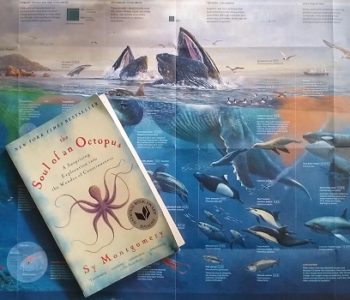

Book Review of The Music of Color by Shimura Fukumi

The essential difference between On Color and The Music of Color can be found in their titles. Whereas Kastan’s and Farthing’s title asserts that it will broadly cover the topic that is color (and is also subtly domineering, as if the authors are standing on top of all the colors and have decided to describe the hues trampled beneath their Oxford boots), Fukumi’s title is synaesthetic, pulling two senses together in a rhythmic way that suggests her text will be a poetic consideration of hues.

Her actual content is even more synaesthetic than that, considering that she is “widely known as a master of plant-based dyes and tsumugi-ori weaving” (Preface to the English Edition). So the text is written by an expert crafts-person who is considering the “music of color” that permeates her textural/textile work. Punctuating the linguistic matter are Inoue Takao’s photographs of both her textiles and the plants she uses to dye, escalating the book’s sensory effect on the reader: not only do we experience words describing a mingling of texture, sound, and color, we’re also immersed in visual fragments that render those words. And let’s not forget the feel of the book itself, with its slightly embossed glossy title printed on a cream-colored softcover that feels like beech bark to the touch.

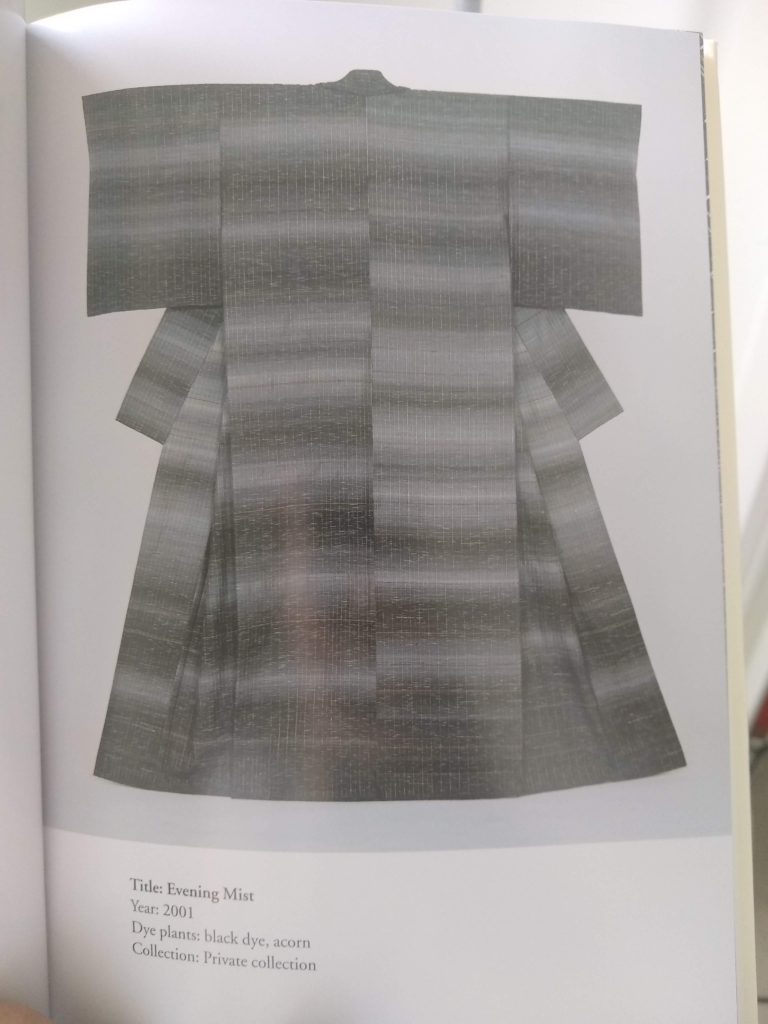

This collection of Fukumi’s essays was originally published in Japan in 1998 and the first English edition of The Music of Color, translated by Matt Treyvaud, was released in March 2019. But before we even get to the copyright page with this info, the book gifts us with sixteen of Takao’s photographs of Fukumi’s colorful woven masterpieces. These kimonos are quite literally ineffable: words cannot adequately convey the complexity of rippling green and indigo streaks of “Wind in the Pines,” the rusty foliage hues of “Autumn Excursion,” or the glowing darkness of “Evening Mist.” The kimonos wear the colors of the plants used to dye them, including the flora’s seasonality, and the titles manifest and amplify the garments’ meanings. It’s a striking fusion of art — harvesting, dyeing, weaving, writing, and photographing — and I can only imagine how enthralling it would be to see the kimonos in-person, The Music of Color in-hand.

Where Chapter 1 of On Color took a giant detour around its ostensible subject, the first essay in The Music of Color, “The Lives of Plants,” is exactly that: a poetic delving into vegetation and the colorful gifts they provide. Fukumi muses that “in the years since I entered the dyer’s way, I have received color without limit from the natural world — a flood too great for this meager vessel to contain. Like a joyful child with a new set of paints, I have spent my days dyeing and weaving with the gifts of the grasses and trees” (9). Her approach is the polar opposite of Kastan’s and Farthings faux-theoretical fumbling around the subject: here we have a lyrical painting of the plants that fill our lives with color and literally color her yarn.

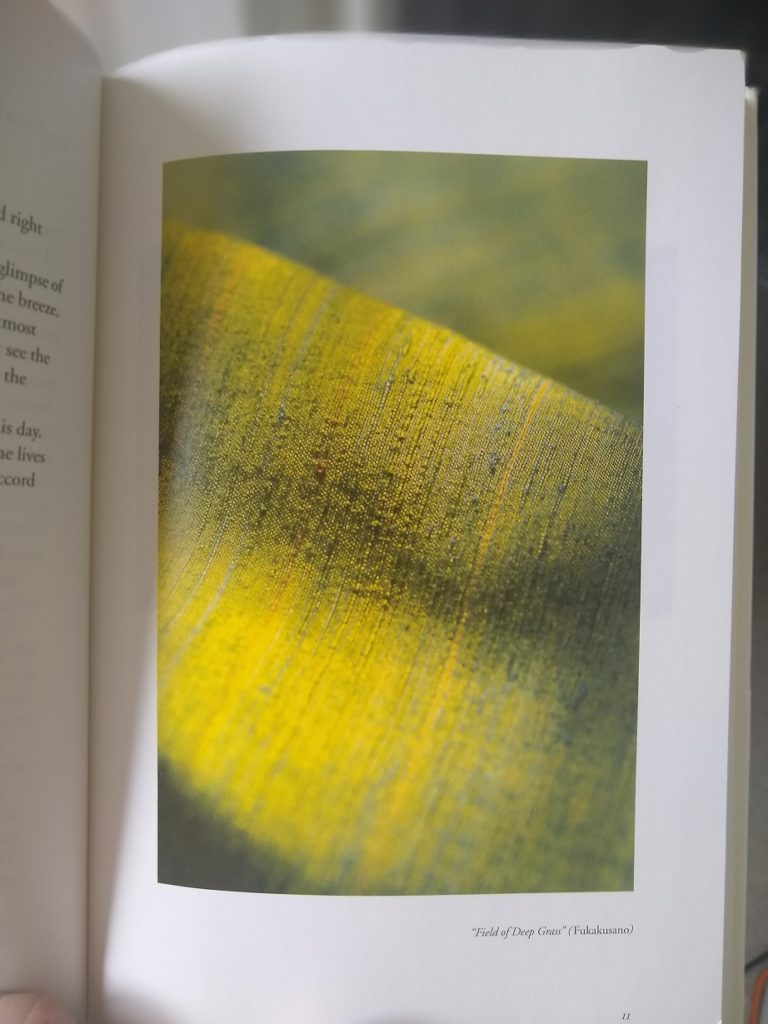

The accompanying up-close photo of her “Field of Deep Grass” kimono, which looks like rolling green hills striped with late-summer, late-afternoon sunlight, adds extra texture, movement, and color to her words. This image is then followed by a photo of a waste silk pile in sunlight, the threads tinted red, gold, olive green, orange, and brown, which itself faces an image of trees bearing their finest autumn hues of red, gold, orange, and so on. The waste silk, still beautiful even in its cast-aside soft chaos, mirrors the deciduous tree image captioned, “Receiving color” — which is also the title of the next essay, which explains, “the colors we receive are already there, within the plants. Our task is simply to bring them across to our side unharmed, and give them a place to stay” (14). There’s a wonderful fluidity to the content, like the subtle transitions between seasons.

Indeed, The Music of Color is, at core, a celebration of the living hues Fukumi has received from the natural world — both in terms of the physical color extracted from leaves, flowers, and branches, and the sensory inspiration for her pieces she draws from the environment. In turn, Takao’s photographs receive Fukumi’s textual imagery and grant it extra dimension via dynamic images of her cloth art and the environment that nurtured its creation.

Each essay in The Music of Color is only one or two pages, so they feel more like prose poems than essays. This brevity increases poignancy; where Kastan waffles, Fukumi rivets. In “The Scent of Sakura,” she describes how she “met an old man who gave me one of the branches he was pruning from the sakura trees. Back in my studio, I simmered it into a dye that turned the fabric such a beautiful pink it seemed to fill my room with the fragrance of the blossoms. At that moment, I experienced what it was like to smell a color” (15). Like the auditory/visual synaesthesia of the title, Fukumi presents an olfactory/visual synthesis, so that we too can smell pink emanating from the page. She goes on to describe how with a later batch of prunings in September, “the dye did not have the same ‘fragrance’ as before. The color was the same gray-tinged pink, but it lacked the previous batch’s radiance” (15). The concept of natural color is presented through imagery, figurative language, and a lived poetic experience — a refreshing contrast to the source-laden prose of Kastan’s and Farthing’s On Color.

Fukumi’s book reads like watching peach, cream, and pink blossoms rippling onto a still pool of water filled with the reflections of olive-green leaves, indigo sky, white clouds, brown earth, and gold sun. In some sense, it’s the unclassifiable form I referred to above in the On Color book review, but whereas Kastan and Farthing end up running around like two clowns trying to scoop up the pond with their arms and dump it into color-coded buckets, Fukumi stands on the shore and studies the water, knowing that to dip in a finger is to disrupt the natural kaleidoscope of beauty.

Many of the essays focus on specific plants and their resultant colors. For example, in “The Kariyasu of Mount Ibuki,” we learn that the kariyasu grass serves as a bottom dye, and “its blue-tinged gold disappears into the indigo vat only to become a dazzling green when the piece is pulled back out…silently playing its part without ever revealing itself directly” (25). And in “The Life of Indigo,” Fukumi traces the narrative of indigo leaves, from “the early days of shining pale blue” to the “first appearance of the quiet, dignified color known as kame-nozoku — ‘a peek into the vat’…if it were a sound, it would be the faintest of whispers; if a scent, the perfume of a stranger passing by” (33).

However, other pieces are broader considerations of weaving and Japanese culture. For example, in “Gleanings from the Sample Box,” Fukumi describes her fabric “scraps like fragments of a mosaic. Scraps like a cross-section of marble. Scraps like streetlights in the rain…” (74) and her turning of these shorn pieces into a sample book. In “Tsumugi and Kasuri” she delves into a type of broken silk that silk farmers keep for themselves, and which hasn’t been traditionally considered suitable for use in garments for formal occasions. However, Fukumi decides to “ignore value systems imposed by others and continue combining the materials gifted us by nature with the best designs humanity can devise to create ever lovelier things to wear” (104). In some sense, The Music of Color is a manifesto from a master, and no matter her focus, she’s able to extract the most vivid colors.

That being said, there were a few moments where The Music of Color plucked a wrong chord — or more accurately, forgot to pluck a chord. For example, “Three-Span Aprons” is an interesting description of the oharame and its functionality, but that’s it; it doesn’t have the poetic tint nearly every other chapter does. Another such moment is in the two actual poems that Fukumi includes in her text. While they’re nice and pleasant, her prose is so much more easily lyrical than her words in stanza form, the poems end up feeling forced in comparison with her essays.

The Music of Color by Shimura Fukumi brims with a wide range of topics: color, culture, fashion, craft, design, nature, language, literature, photography, botany, and philosophy. While writing this review, I kept trying to figure out a term that could encapsulate the poetic fusion of so many different elements in a singular piece that ripples with life, vibrancy, and dynamism, and then I realized it was right in front of me: Fukumi has woven her musings into a breathing fabric that is The Music of Color. This is a book that I will turn to again and again to discover new ripples in its waters.

ISBN OF EDITION READ: 9784866580616

Notes of Oak Literary Blog Book Review Score for: The Music of Color by Shimura Fukumi

8/10

1 COMMENT

“cast-aside soft chaos” – I like that.

I’m looking forward to reading The Music of Color.