Discover Literature

Discover Literature

Ekphrastic Poetry: When Art Kindles Literature

MAGIC HAPPENS WHEN POETS RUMINATE ON MASTERPIECES

Ekphrastic poetry is right up there with the villanelle, the ghazal, the abecedarian, and other specific poetic forms that lead a highly intramural existence: poets know what they are, but rarely write them once they leave the MFA creative writing programs where they’re required to spit out such guided assignments. The problem is that in the real world, most readers don’t know what the hell those words mean, let alone the nuances of each form, and as a poet struggling to make even $5 off a poem — actually, make that even $1 — there’s no point in also struggling to write poems that have ground rules: we poets must have some small joy in our feats of creation.

But what a loss! All of those types of poetry, and the one we’re here to discuss today — ekphrastic poetry — can crack the shell on pithy nuts of insight that will never otherwise be opened through our usual, more organic modes of inspiration and composition. Thus, this blog post will hopefully educate readers on the joys of an unfamiliar type of poetry, and also rouse writers from their creative stupor — including myself.

A Willy-Nilly Definition of Ekphrastic Poetry

Whether it’s a painting or a poem, good art evokes an emotional and intellectual response in the viewer — regardless of their expertise in the medium of expression. In a non-artistic audience, such stimulation might prompt the viewer to be more affectionate, or take a walk outside, or to see a doorway differently. In other words, the response is typically a simple, personal perspective change. But when an artist sees a work of art, it can catalyze inspiration in their own art form, and in literature, the result is ekphrastic poetry.

Ekphrastic poetry most often refers to a poem written about a visual work of art, such as a painting or a sculpture. The OED defines “ekphrastic” as: “Employing, characterized by, or relating to a literary device in which a painting, sculpture, or other work of visual art is described in detail.” An ekphrastic poem can thus be thought of as a literary work that is plump with poetic imagery about visual imagery created by another artist.

But the dictionary definition leaves room for interpretation. A photograph surely qualifies as an “other work of visual art,” as does a tapestry, a mosaic, or a building’s architecture. We could push things a little further and argue that the rose pattern on your sofa cushion, the nice wooden chair with the woven straw seat you’re sitting in, the calligraphy on an envelope, a wind chime dangling on your porch, or even a film can all also qualify as visual works of art. This vein could lead to long-winded debates on the nature of a “work of art,” but artwork that the word “ekphrastic” doesn’t immediately and traditionally conjure up is worth mining for its potential poetic ore.

We might question tradition even further and ask whether ekphrastic poetry must necessarily be about a visual work of art. After all, if we look at the core word, “ekphrasis,” we learn from the OED that: “Originally: an explanation or description of something, esp. as a rhetorical device. Now: spec. a literary device in which a painting, sculpture, or other work of visual art is described in detail.” Indeed, the yolking of ekphrasis to only visual masterpieces is a recent linking conducted by poetry prudes, and it’s a tenuous one at that. The word has a long, ambiguous history, with ancient origins in dusty Greek classrooms where students learned to use highly detailed descriptions to convey the experience of a thing, person, or place to their audience as a form of rhetorical sashaying.

Thus, I would argue that ekphrastic poetry can also be written about music, dance, and more. An ekphrastic poem about a symphony would necessarily contain copious amounts of onomatopoeia and synaesthesia, making for an engaging and sensual literary experience, and it would require the poet to interact with a creation that conveys meaning without words, just like with visual art.

But an even more interesting debate is whether ekphrastic poetry can be written about other poetry. After all, poetry is an image on the page that produces more images when read, and I’d be quite interested in reading a poem that vividly illustrates another poem. Perhaps the answer can only be learned through exercise. In short, I think the key to creating engaging ekphrastic poetry is to return to the phrase’s roots and set out to describe the work of art in question — whatever it may be — in electrifying detail, so that the poem amplifies the source.

Finally, while most common readers will have never heard of ekphrastic poetry, only going so far as to define such pieces that they have encountered as “poems about pictures,” the phrase is kicked around in MFA programs like a hacky sack. For homework, professors send students off to find works of art that spark their creative juices so that they can bring in their resulting poem to workshop the next week. And despite the fact that most students will spend no more than five minutes picking their piece, unerringly migrating to the images we all know — “The Starry Night,” “The Scream,” “David,” “The Persistence of Memory,” and so on — the exercise is a good one because it forces young writers to stop drinking from the inspirational wellspring they are accustomed to (a wellspring that is very often dry of imagery), and to approach their poem through a new aquifer. And the result is usually, finally, poetry that abounds with colors, light, shadows, textures, and overall vividness that is woefully scarce in other workshopped poems.

Ekphrastic Poem Elements

We’ve established that ekphrastic poetry is somewhat nebulous as a form, but that doesn’t mean we can’t try to describe some of the stones steadily shimmering up through its rippling waters.

LUCID DETAIL — This is a requirement of ekphrastic poetry — the single biggest boulder that anchors the poem to the form. An ekphrastic poem must be scaled with description derived from its source, such that you can hear the words slithering through the grass, vines, and leaves of the page. It must be variegated, and if its inspiration operates in colorless realms, it must emit the grey mists and bright blanknesses of the depths of that dearth. An ekphrastic poem must animate the most muted detail on the art it’s describing, bringing to life the onion-shaped rock smudged into the corner beside the white blob of the stoop. Without description, without imagery, no poem can function, but an ekphrastic poem will be even more leaden, bogged down by the pale, shapeless weight of its artistic source, like a log overtaken by ghostly fungi sinking into a bog.

POETIC RESPONSE — Through such intensive detail, ekphrastic poetry must attempt to impart the intellectual and emotional response evoked by the inspiring art. Remember, when someone reads an ekphrastic poem, they don’t always have the corresponding art in front of them, nor have they always already seen it; they only have the poet’s interpretation. This interpretation must convey the core of the original work and also amplify it by presenting the effect the piece had/can have through the combination of its various elements. Thus, an ekphrastic poem includes the poet’s intellectual and emotional energy that was stirred up by the animus of the work of art, to be presented like a steaming cauldron of yellow curry for the reader to dip into and pull out nourishing potato pieces.

FOCUS – An ekphrastic poem should not wander off to examine someone’s clog while in the midst of presenting a perspective on Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s “The Wassail.” Tangents are not forbidden, but they must bolster the interpretation of the artistic source rather than distract from it. After all, the main task of an ekphrastic poem is to intensify a piece of art’s impression through descriptive, attentive language.

A PORTRAIT OF THE ARTIST(S) — Though it’s not necessary, many ekphrastic poems will pull in the figure of the artist behind the work of art, so that the writing becomes almost biographical. In describing or hypothesizing about the mood and intent of the artist, the painting, sculpture, etc., being conjured up attains character, context, and depth. At the same time, the poet may also bring their own figure into the poem (see Sexton’s poem below), to create a bifocal lens with a meta-view of literature being written about art.

A PORTRAIT OF THE AUDIENCE — In a similar way, ekphrastic poems may also pull the audience itself into the roiling, colorful, complex soup that is words about other art. This breaking of the fourth wall has two effects: it helps the reader feel a certain sense of community with all the other people who have actually seen the original work, and it draws the reader’s attention to the fact that they are reading a poem about a work of art. Along those lines, an ekphrastic poem should make itself clear to its audience that it is an ekphrastic poem.

ARTWORK’S DERIVATIVE — Finally, ekphrastic poetry must revolve around a source that can be categorized as art. The poem cannot spring from nowhere; if it does, it’s simply a poem. The poet must identify one or several compositions — whether painting, song, or something else — as art, and from that definition, proceed to compose the literary piece. In other words, to write an ekphrastic poem, the poet must sit down with the goal of writing an ekphrastic poem about a creation they’ve already pin-pointed.

Ekphrastic Poem Literary Analysis:

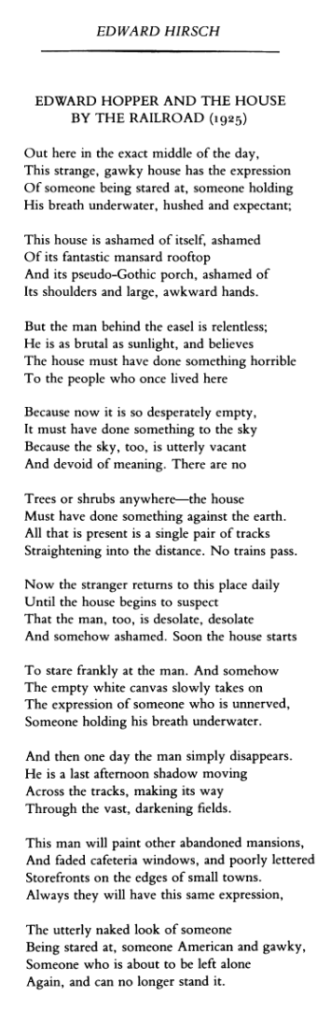

Edward Hirsch’s “Edward Hopper and the House By the Railroad (1925)”

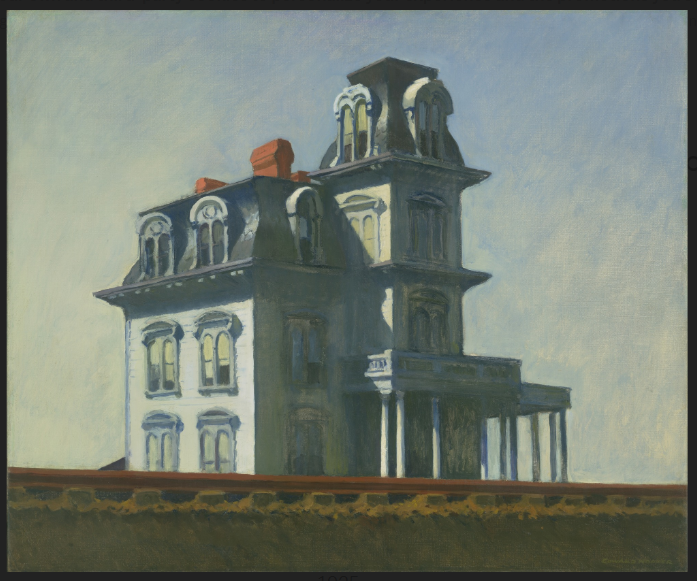

It’s about time we read an actual ekphrastic poem. We’ll avoid the example that immediately comes to mind — Keats’s “Ode on a Grecian Urn” (though you should read it on your own time as a refresher in how exasperatingly flouncy but spellbinding Romantic poetry is) — and instead turn to Ed on Ed. Edward Hirsch’s “Edward Hopper and the House By the Railroad (1925)” is an ekphrastic poem about the following Hopper painting:

Let’s look at the poem:

Hirsch’s poem immediately identifies itself as ekphrastic poetry via its title: the title declares that the following literary piece is going to be about Edward Hopper’s painting, “House by the Railroad.” At the same time, it also suggests that the poem will look at Hopper himself and his relationship to this particular work of art. Such a title invites readers to look up the painting that is being written about, so that they have the visual reference while they wend through the words — though of course, only some will actually go do this.

The poem’s first line is pure chronotope that sets the when and where of the poem and the painting; this is an ambiguous where clashing with the precise moment of when — just like in the painted reference. With no landmarks offering context, and with the view severed by the painting’s natural edges, Hopper’s house is simply “out here” (1). At the same time, the painting occupies a singular, unchanging moment in time that Hirsch pins down as “the exact middle of the day” (1), with this specificity and ambiguity instantly catapulting the reader into a familiar but unplaceable region that mimics the painting’s mood of disquiet.

Hirsch then jumps into a description of the house, and uses personifying language to imbue it with the character being emoted by the building in the painting. Indeed, because we have the picture as reference, as soon as we read Hirsch’s words, they seem spot-on; the house does look “strange [and] gawky” (2) and “has the expression/of someone being stared at” (2-3) — though we might not have formulated those descriptions on our own. Beyond being a precise rendering of the house, that latter line also draws attention to the fact that the structure has been scrutinized by the painter, and is now being studied by the reader through the lens of the poem.

The second stanza continues the personification and offers an interesting layering of art forms: we are reading a poem describing the architectural elements captured in a painting. This artistic tripling leads to a scenic breakthrough in the poem’s narrative in the third stanza: not only is the house present, so is “the man behind the easel” (9). This is when it becomes clear that Hirsch is granting us access to not only a description of the painting, but also the process of the painting: we are located in Hopper’s act of composition in 1925. This is quite a delightful play with time, space, and art: although Hirsch surely used Hopper’s painting as inspiration, through the vehicle of the poem, the poet can transcend the picture’s static existence and transport the reader back through decades to the real house. This is only possible because we still have the simulacra — the painting of the house — as reference.

At the same time, Hirsch extrapolates Hopper’s own identity from the house presented in the painting, and in turn paints a picture of Hopper as “relentless” (9) and “brutal” (10). From stanza three to four, Hirsch also takes the liberty of stating what Hopper “believes” (10), and indeed, ekphrastic poetry allows for such presumptions and license. When any artist enters their work into the public sphere, it becomes open to interpretation, and an ekphrastic poem is an opportunity to present this interpretation, with the poem serving as the poet’s thesis about the composition — a thesis supported by vibrant descriptions.

In stanzas four and five, Hirsch circles back to a description of the house, which opens up to a larger description of the painting. We are simultaneously in Hopper’s moment of composition, and in the composition, where “the sky, too, is utterly vacant/and devoid of meaning. There are no//trees or scrubs anywhere…all that is present is a single pair of tracks/straightening into the distance. No trains pass” (15-20). The overall ambience is one of emptiness and desolation. This is present in/presented by the painting, but it’s also arising out of Hirsch’s emotional reaction to the painting. When the poet looks at “House by the Railroad,” he feels bleakness, solitude, and stagnancy — something another viewer might not feel so acutely — and has infused his poetic reaction with these sentiments. Further, the brief sentence “No trains pass” is also a playful-but-nihilistic reference to the inherent fixed state of a painting: no trains pass in Hopper’s painted landscape and no trains will ever pass because the painting has captured a moment when no locomotive is rolling through. At the same time, by drawing attention to this fact, Hirsch linguistically brings the idea of a train into the picture, which results in an even greater melancholy once the reader realizes that it’s a potential traversal that can never happen.

Things get even more complex in the sixth stanza, with Hirsch revealing that although the painting traps us in a singular moment, we are also reading about the many-day process of Hopper’s composition, with the painter returning to the site “daily” (21). As we watch Hirsch watch the painter, the house watches the painter back, until the house’s scrutiny of its purveyor gets translated onto the canvas. After viewing the painting, Hirsch has peeled back Hopper’s creative process to argue that the energy of the painted object has taken on the demeanor of its creator. Much the same thing is happening in this poem itself: both the painting and the historical figure of Edward Hopper are becoming vessels for Hirsch’s own intellectual reaction in this ekphrastic poem.

In the eighth stanza, Hirsch literally “fades out” the poetic focus from the painting that occupied the first part of the poem. Hopper becomes a “last afternoon shadow moving/across the tracks” (30-31) — a statement that once again draws attention to ekphrasis’s ability to challenge the static nature of completed art. Hirsch follows Hopper’s shadow out of the confines of the singular painting to his larger body of work, which is filled with buildings that “always they will have this same expression” (36); we are allowed to escape the painting, even if it’s only to see other just-as-desolate paintings.

In the final stanza, a quadruple abandonment occurs that is a result of this being an ekphrastic poem: 1) the initial abandonment of the structures that Hopper chooses to paint; 2) Hopper’s abandonment of the structures once he completes his paintings; 3) Hirsch’s abandonment of his scrutiny of the artist and his paintings; and 4) the reader’s abandonment of the poem because it comes to an end. Just as the final two lines suggest, we are suddenly left with an overwhelming feeling of being deserted by the poem — which is exactly the feeling conveyed by Hopper’s original image. In his poem, Hirsch both embodies the painting’s effect and reproduces it/expands upon it in extreme form.

On a critical note, I would like a bit more color in Hirsch’s poem; after all, Hopper’s painting is not totally devoid of color. The crimson beacon of the chimney is glaringly absent from Hirsch’s rendering of the painting, and the yellow-blue of the sky is mirrored in the light blue of the house and the sickly yellow windows. Hirsch touches upon this idea in stanza four, but not in actual description. However, overall this is quite effective ekphrastic poetry: the writer has presented, interpreted, and intensified a painting.

Ekphrastic Poetry Examples at a Glance

Poets have been getting their ekphrasis on since, well, Homer, so there are tons of poems about works of art out there. Here are some to whet your appetite even further, with only brief commentary.

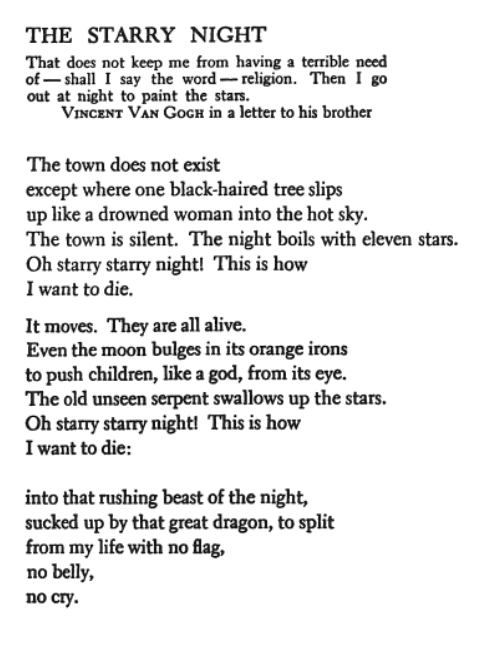

Sexton on Van Gogh

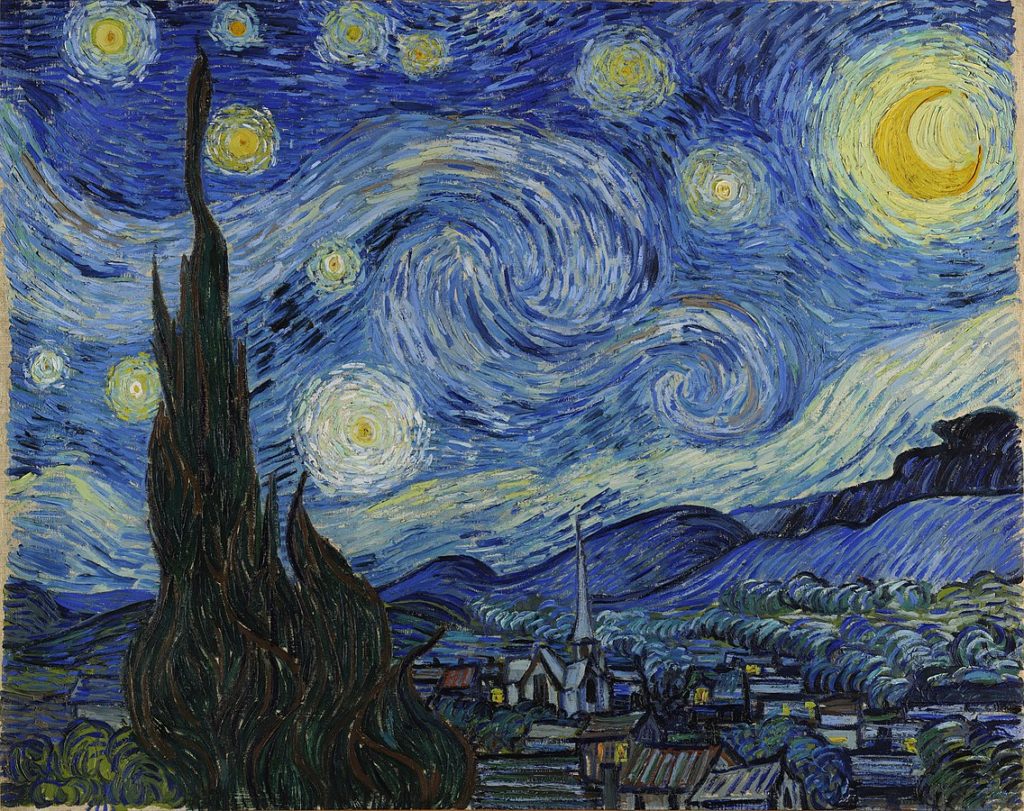

Just because a painting is globally familiar doesn’t mean that ekphrastic poetry can’t be written about it. Indeed (and what those MFA students will argue), producing art about famous art can rejuvenate the original piece — not in the sense of making it better, but rather, in forcing the audience to remember, relearn, and see anew what made the painting a masterpiece in the first place.

Thus, we have Anne Sexton’s ekphrastic poem “The Starry Night” about Vincent Van Gogh’s oil painting “The Starry Night.” In it, you’ll find Sexton coalescing with the memory of Vincent via the swirling, tempestuous, feral, and colorful portal of the famous painting.

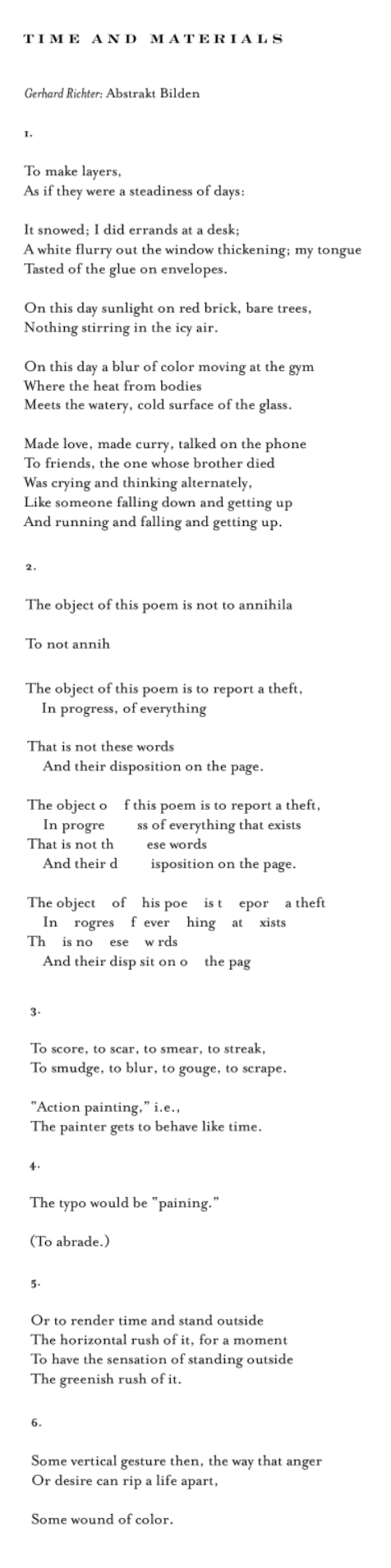

Hass on Richter

In some cases, the ekphrastic poem’s very own structure begins to feel like the artwork that inspired it. Such is the case in Robert Hass’s poem “Time and Materials,” which springs from Gerhard Richter’s collection of paintings, “Abstrakt Bilden.” Yes, ekphrastic poetry need not stick to one piece of art in its focus. Here are some of Richter’s oil paintings:

And here is Hass’s poem:

Ekphrastic Poetry In Conclusion

When art meets art, the confines of time, the page, and the frame, and the medium become hyper permeable. For readers, ekphrastic poetry exposes them to different modes of composition and provides them with material rich with detail, depth, and connections across eras and spaces. For us writers, thinking about other modes of creation while engaging in the act of writing allows us to get a glimpse of the brume at the root of all masterpieces — that dim, glowing core that guides pen, paintbrush, chisel, camera, and more — that orb that we see as briefly as a direct look at the sun, the brightness lingering on and calling us to forge.

5 COMMENTS

Thank you for this! Leading a group of students through an ekphrastic experience this summer, and your thorough overview is enhancing my plans!

Delighted to contribute to the nourishment of poetry in education!

[…] clever are these? Oh, to have such talent, patience and application. I feel a couple of Ekphrastic poems coming on… watch this […]

Thank you for this. Beautifully written. (Where can I find your poetry?) I am writing about Dickens and am bouncing off GH Lewes’s contention that D was a seer seeing visions. Although Lewes thinks this makes D. a lesser writer I think it exalts him. D is painterly especially when he describes the sprawl and menace of London. I feel when I comment on his descriptions I am verging on ekphrasis. (see Nickleby, Chapter 32 pars.5-6) Thanks again!

Btw that Dickens passage ends with a reference to Hans Holbein’s prints “Dance of Death”!