Book Review

Book Review

DJ Waldie’s ‘Where Are We Now’ Finds LA’s Pulse

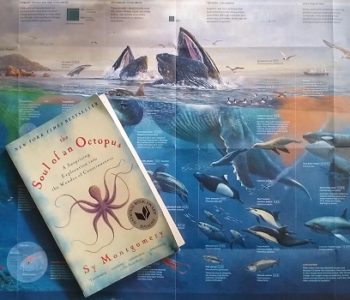

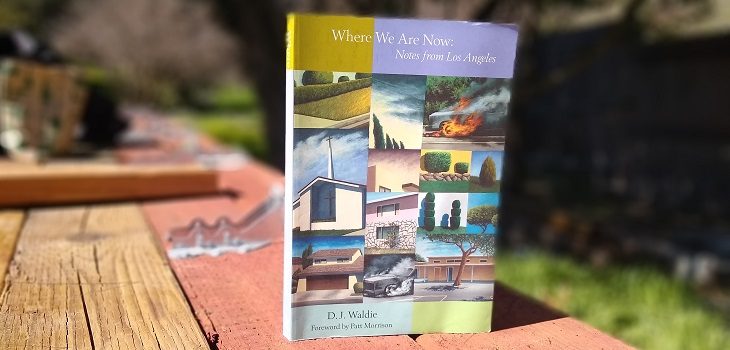

A BOOK REVIEW OF D.J. WALDIE’S 2004 NONFICTION COLLECTION WHERE ARE WE NOW: NOTES FROM LOS ANGELES

If you’re like me, the name D.J. Waldie immediately evokes L.A. suburbs and the unique prose “blocks” writing style that he used in his most famous work, Holy Land (1995), to represent the layout of that tract housing. However, in his 2004 collection of essays composed over a decade, Where Are We Now: Notes from Los Angeles, Waldie wrenches himself from Lakewood, CA and attends to Los Angeles with a bird’s eye historical and geographical view. Is the result as successful as Holy Land, which is considered quintessential wider-L.A. region reading? Read on to find out.

THE PREDICAMENT THAT IS LOS ANGELES

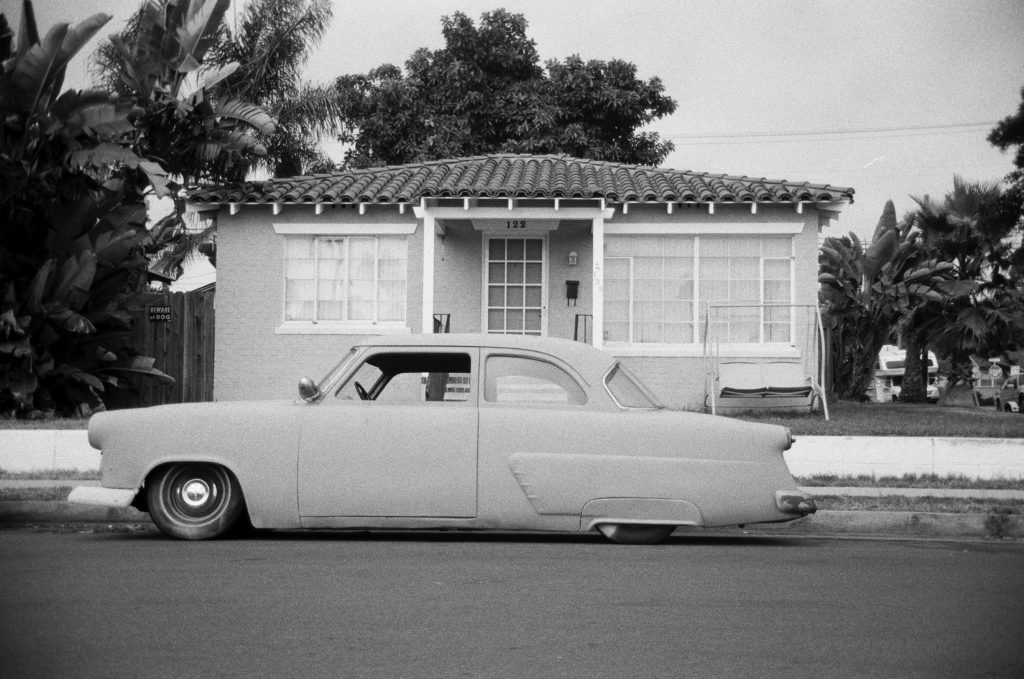

Los Angeles, through its development, erasures, and pure breadth, has come to be seen as the unclassifiable city. The city that is not a city. A tabular entity built on whims, images, and dreams, with this very image of ambiguity serving as the newest nostrum: come out to sunny L.A., this place that is nowhere, everywhere, and all your nitty-gritty woes will evaporate in its enigma.

People who’ve lived here their whole lives, those who’ve just arrived, and those who’ve never even set foot here see Los Angeles as this endless city that is not a city. Even writers who proclaim not to believe it, who sense that L.A. has a single-sentence thesis hidden within it, must first wade through the muddy waters of its misrepresentation as indescribable, and in doing so, end up lost in Los Angeles’s sprawl, unintentionally revealing that Los Angeles’s thesis is that it has no thesis.

Unwieldy city. Controlled city. Vibrant city. Noir city. Massive city. Missing city. A city that seems to persist through the frictions of its own contradictions. Perhaps Los Angeles’s greatest attribute is that nobody will ever quite be able to find its true heart, and so there will always be artists feeling for its pulse and producing engaging creative works in the process.

A BOOK BY, FOR, AND ABOUT ANGELEÑOS

D.J. Waldie’s Where Are We Now: Notes from Los Angeles is one such text that seeks to chart L.A.’s heartbeat by collecting “a decade of Waldie’s essays and observations about the city’s rapid evolution.” Published in 2004 by the Santa Monica-based Angel City Press, this book compiles Waldie’s “notes” on various L.A.-oriented subjects, from the history of The Los Angeles Times, to public transportation, to analyses of other artists’ takes on Los Angeles. Together, the pieces provide a motley clarity on the political, infrastructural, ecological, and historical environment of the city during the late 1990s to the early 2000s.

This is a local L.A. book written by a local writer and published by a local press — that’s as L.A. as it gets. And the text seems to be aware of its own localism too: while readers far and wide will find interesting descriptions in its pages, Waldie’s casual naming of locations and landmarks, his persuasive appeals on “provincial” issues, and his frequent use of the collective voice when conceptualizing L.A. (as in the title itself), all indicate that this is a text written for people living in or near the city. In other words, Angeleños and those who, as Waldie explains he is, “are Angeleño[s] by desire” (13), even if their residence doesn’t fall within the city’s official lines.

That’s me! As a Southern California-based writer who, growing up in a town far from L.A., desperately wanted to live in that coastal metropolis, and eventually fulfilled that wish by moving to L.A. county and going to UCLA, I scour L.A.-focused texts like a fortune teller’s orb for the secret to the city and to inform my own writing about this strange paradise. As such, in the same way that a number of pieces in Where Are We Now counter other artists’ visions of L.A., this book review has likely been skewed by my personal biases about living in Los Angeles. Every artist thinks every other artist doesn’t render L.A. quite right, but it always comes from the same insecurity: every artist knows that they themselves can’t render L.A. quite right, and so the only solution is to try to find an answer in the negation of other interpretations.

In Where Are We Now, Waldie ventures into suburbia in several essays, but he does a good job otherwise at not covering the same territory of Holy Land. This is a work that takes on a bigger Los Angeles, both geographically and temporally, and not just the microcosm of his hometown (though his lifelong captivation with old-suburban Lakewood not as a place of existential captivity, but comforting inspiration oozes through at moments and you can just tell that he’d rather be talking about life in his tract house). As a whole, this text feels like a book about L.A. — not simply a collection — despite many of the pieces previously appearing in different form in publications such as The New York Times and The Los Angeles Times.

A HETEROGENEOUS TEXT JUST LIKE THIS CITY

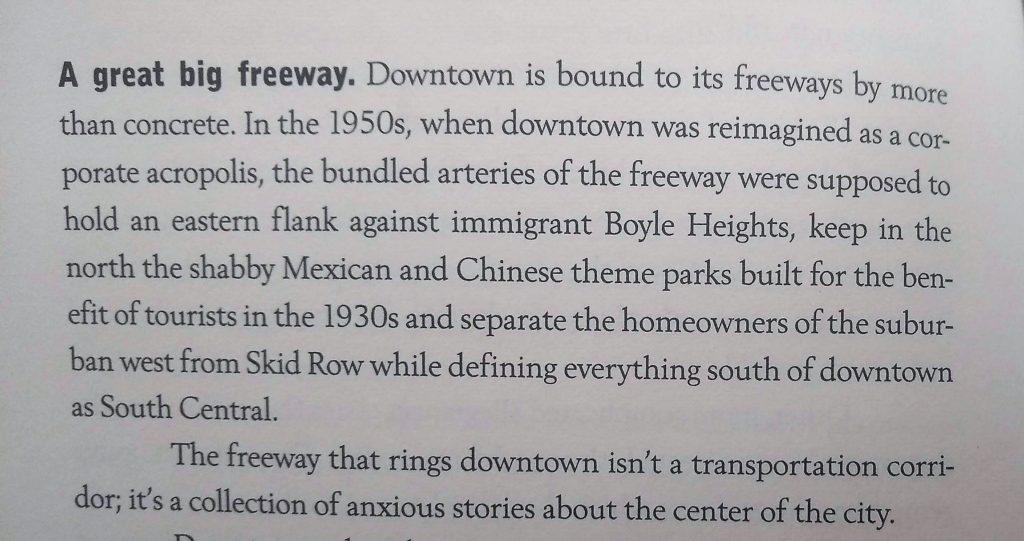

The individual pieces compiled in Where Are We Now read like fusions between essays, newspaper op-ed pieces, and notes left out on a wood table in a library. They tend to proceed casually, quietly, and quickly, with the shortest piece coming in at less than a page, the longest running twenty pages, and the rest sitting at around five pages. They feel structurally variegated — not unlike Los Angeles. Some of the notes include subheadings that break up the text into shorter (though still long) fragments within the larger “note” in a manner reminiscent of Holy Land‘s format. For example, in “Real City,” some subtitles include “Remembering Downtown,” “The Regime of Speed,” “Thirty-Six Degrees of Memory,” and “Our Downtown.” Such sectional pauses imbue the text with a “breathing” rhythm that pushes these notes closer to prose-poetry, though Waldie’s prose tends to be too rigorously narrative to ever fully cross that line.

An even more interesting “subheading” pops up in “Fallout,” which explores growing up in suburban Lakewood during the Cold War, and “Our Town,” which is a defense of suburbia: a series of graphics showing Los Angeles growing from a single structure to Downtown’s present mass. These two essays stray far from L.A.’s core, so perhaps the graphic is intended to be a visual ballast to the rampant text. In any case, the image of the growing city separating textual blocks parallels the rhetorical arguments Waldie builds in the essays, revealing writing as a form of development.

Or they could just be series of cool illustrations of Los Angeles because that’s what the book’s about.

Overall, Waldie/the publisher use such typographical and structural elements willy-nilly, which culminates in a haphazard aesthetic. However, I much prefer this looseness to a tightly clutched bouquet of essays. Think of Where Are We Now: Notes from Los Angeles as a stack of notes left out for you to gather and peruse while roaming around Los Angeles, holding up each one to the skyline to check for verisimilitude — and while likely sensing that much is missing and much has changed, also being comforted by the feeling of the words in-hand.

The essays are similarly eclectically organized. In the first few notes, we move from an examination of Los Angeles through the filter of its troubling dominating figures (the Chandlers, who owned The Los Angeles Times), to a rebuttal to claims that L.A. sprawls, to a critique of The Truman Show‘s critique of suburbia, to a description of Waldie’s own suburban experience, to an in-depth defense of keeping the L.A. river as a flood-control system, to a mourning of California’s avoidable power shortage issues in 2001. In short, the collection is arranged like Los Angeles: non-chronological and sprawling, but still tied together by the common themes of suburbia, natural resources, bureaucracy, art and entertainment, and transportation.

If you accept that you will drift in DJ Waldie’s Where Are We Now, the only unproductive moments are the shallower, topical pieces wedged in between more robust musings. “The Golden Dream Goes Dark,” for example, begins to explore the myth of endless power in California, and then ends abruptly in the thick of describing the effects on Silicon Valley. Mid-wandering, the reader drops off a cliff. I found myself flipping back to make sure I hadn’t skipped a page. This is likely the result of extraction from some newspaper, where the context and layout would have fended off the abruptness of the article’s brevity, and I wish Waldie had fleshed out the content to meet the demands of book form.

THE CIVILIAN WRITER

Waldie is equal parts L.A. historian, civilian, critic, and poet. He’s adept at shifting between these perspectives, so that staunch facts and ordinary encounters typically have a poetic payout. For example, take a look at this passage from “The City and the River”:

We begin by learning very straightforward facts such as that “since the 1960s, the county’s flood-control system had prevented catastrophic flooding of the small cities on the plain below Los Angeles.” It doesn’t get more prosaic and (ironically) dry than that. But then the next single-sentence paragraph, which is also the last sentence in the section says, “If you live low, as I do, you began in 1987 to worry when you heard the sound of rain” (52). From technical prose, we abruptly shift to the citizen who thinks philosophically about flood control systems and weather, turning them into an anxious feeling heavy with the fragile meaning of being human. This final line’s poetic effect is amplified during the reading experience by 1) its “enjambment” from the prior fact-filled paragraph, 2) its juxtaposed singularity (a single-line paragraph), and 3) its leading to a literal line break/the “white space” of the section break. Here we see Waldie using structural tools from poetry in the arena of prose, to powerful effect. And there are many such moments throughout Where Are We Now. For example:

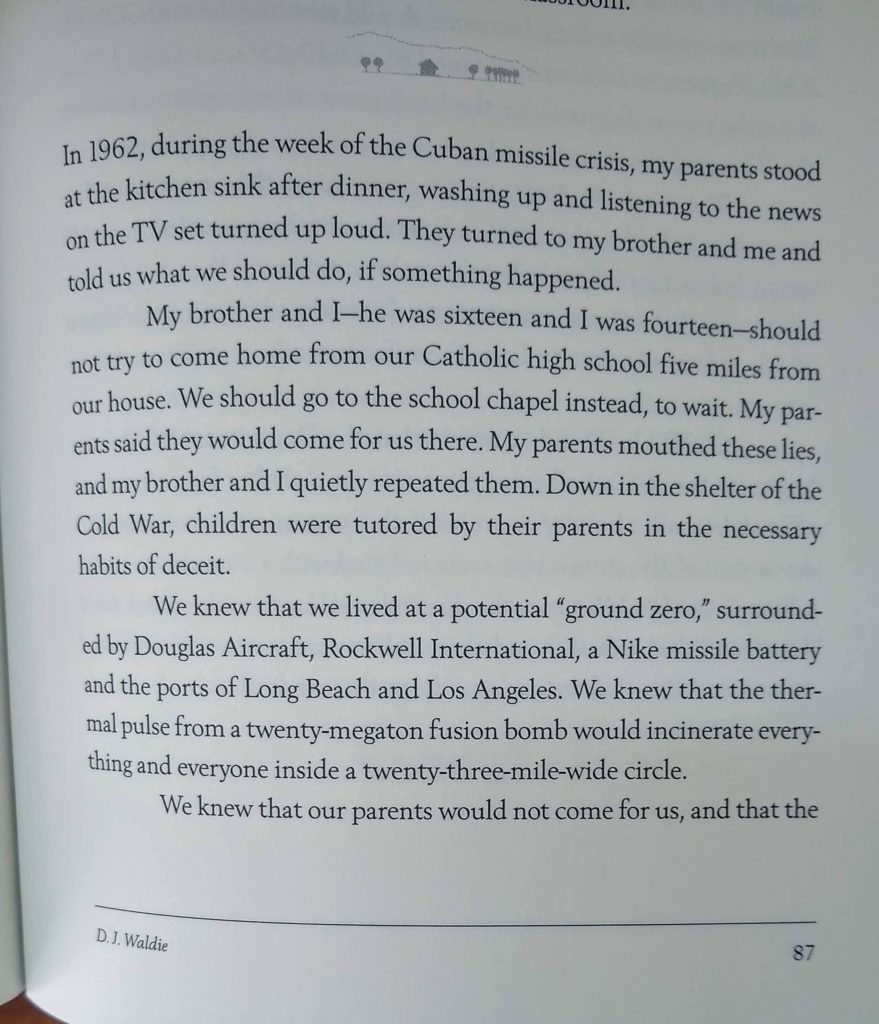

Here again, Waldie takes a series of historical facts and distills them into a discrete sentence that is more lyrical and metaphorical, and that helps drill home the ugly sharpness of the truth. He utilizes this single-sentence paragraph tool again in “Fallout,” which grapples with the morbid reality of growing up in L.A. during the Cold War. Here’s a complete section from this note:

The section begins with the most ordinary of scenes — post-dinner dish-washing with the news on — and ends with the stark self-revelation of death even for teenagers “trained” in surviving a bomb. In being taught how to survive an attack, Waldie and his brother instead learn they would inevitably perish from such an attack. Through these bookends of the ordinary and the lethal that are separated by only a handful of sentences, Waldie underscores the cloud of mortality that permeated every household during the Cold War, and especially those of ordinary people living in “ground zero” areas.

In between those bookends, he utilizes the poetic tool of anaphora to first mimic the repetition of instructions for survival — “We should…”, “We should…” — and then to peel back the veil of these “lies” that he and his brother “quietly repeated” through the undermining anaphora of “We knew…”, “We knew…”, “We knew…” The movement toward reality ironically pivots on this central apohristic line, “Down in the shelter of the Cold War, children were tutored by their parents in the necessary habits of deceit.” No matter that Waldie’s parents reiterated careful instructions for survival, the boys recognized the truth of the grim statistics of the “twenty-megaton fusion bomb” and a “twenty-three-mile-wide circle.” Thus, the repetition that was intended to keep the boys alive, instead descends into the chilling, single-line epiphany — for both the boys and the reader — that, “We knew that our parents would not come for us, and that the school chapel was a fit place in which to die” (87). Once again, this sorrowful line is followed by a section break, granting “die” the weight of the last word.

These truncated sections are when Waldie’s writing feels more like prose poetry than an essay due to pacing, spacing, and rhythm. And while the above doesn’t have much in the way of sensory imagery and figurative language, there are enough strikingly lyrical moments in Where Are We Now to keep me satisfied as a reader. For example, in writing about The Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels in “Hic Domus Dei Est et Porta Coeli,” he explains that it “is not so much a mud-colored building as it is a specific volume of this light. It does not play across the cathedral’s interior surfaces in the way light through stained glass animates the carved figures of cherubs and martyrs in a more sentimental church. When the overcast thickens outside momentarily, the tone of the light inside changes utterly, miraculously, and everywhere at once” (95). Waldie effectively translates the ephemeral and transcendental into concrete, vivid language, which is the hallmark of a poet.

Another remarkable image appears in “On the Bus,” which is my favorite essay in the book:

But the Rapid buses are lords of the street and in nearly continuous motion. An aggressive motorist might find the sweet spot in the outside lane next to one of those ultimate SUVs and ride the wash of its speed through green light after extended green light, like a dolphin surfing the bow wave of a freighter.”

-From “On the Bus” (142)

What an absolutely striking visual. It synthesizes the sooty and solid with the sleek and liquid in a refreshing textural tapestry that transforms an ugly mechanical scenario into something natural and magical.

As a former L.A. bus rider, I particularly enjoyed Waldie’s bus essay because I was so familiar with everything described in it. Indeed, the piece proved the nonexistent theory that if you put two writers into the thick of L.A.’s public transportation, they will inevitably notice and think the exact same things. Waldie tells us that, “On the night bus it’s the passengers who are on display — unlike motorists at night, who are invisible in their cars — and the bright overhead lights turn the pairs of facing bus windows into both showcases and partial mirrors that re-reflect faces like a carnival fun house” (142), and that, “time is different once you’re on the bus…you’re free to read, gawk at the passing scene, daydream or risk sleep” (139). Many times on my nightly journey home from school, I’d look out the bus window toward the streets, hoping to see where we were, only to be met with my sallow reflection trapped in the plastic glass. Every nocturnal bus ride means facing your ghostly doppelganger in the window, an eerie passenger sitting in the corner of your eye, unless you’re lucky enough to have a driver who turns off the lights so you can “risk sleep” as Waldie so accurately explains: even as the bus’s rhythm lulls you — invites you to nap to make time pass quicker — if you doze off, you risk missing your stop and ending up somewhere where you have no idea how to get home (though L.A.’s pulse seems to beat louder in these moments of being lost).

WHAT DO WE DO ABOUT LOS ANGELES IN D.J. WALDIE’S WHERE ARE WE NOW

Despite the fact that Waldie has (willingly) lived in a suburban area divorced from the core of Los Angeles his entire life, in Where Are We Now: Notes from Los Angeles, he demonstrates a certain clairvoyance about the predicament that is Los Angeles. That is, he understands that the problems of this metropolis, with its river turned to concrete, its scarcity of water and power, its acres and acres of single family homes, and so on — cannot be solved easily, if at all. His skeptical optimism is both frustrating and convincing.

For example, in the essay, “The City and the River,” Waldie traces the history of the Los Angeles River, from the environmental injustice of the city relegating people of color to its flood-prone banks in the 1800s, to the waterway later being swaddled in a concrete flood-control system still at risk of inundating the primarily working class homes along its path, to the beginning of piecemeal greening of some of its banks in the early 2000s. As a proponent of habitat restoration, I immediately wanted to disagree with his statement that, “the river will always be a flood-control channel, constrained by concrete to protect working-class households on the floodplain” (70) — I wanted to say to say that there must be some way to restore the entire river to its original, natural state in a manner that allows people to live safely beside it, but the reality is that there isn’t. As Waldie foresaw in 2003, the only solution now is to restore certain parts of the river, which will allow some native wildlife to hopefully make a comeback and provide more green space for the public.

Similarly, in “Et in Arcadia, Ego,” in analyzing Brechin and Dawson’s photography book, Farewell, Promised Land, Waldie comes to the grim conclusion that, “Muir’s sublime California was gone the moment he trekked across it. In his wake, and behind all the miners, lumbermen, ranchers and subdividers, is a California that we have made our imperfect home” (82). From Brechin, he extracts the idea of “gardening” in the sense that, “When the mining is over, in all the ways California has been mined, then gardening begins as our permanent act of complicity with this place” (82). Waldie ultimately takes it upon himself to literally begin gardening in his own front yard, but implies that the metaphor could extend to thinking about bigger spaces that we have already trampled — though he doesn’t offer much more guidance on what we should do. This kind of bleak honing in on the reality of Los Angeles’s resource issues without a corresponding, clear-cut solution could easily convince a reader to give up — to say, Welp, why should we even try if “Los Angeles is the Paradise we’ve ruined” (15) and we’re always going to have a gutter for a river.

However, the text isn’t totally devoid of hope. I think. In the “Pornography of Despair,” he explains that, “To believe that no story can stand against the catastrophe that is L.A. would be L.A.’s ultimate disaster” (161). In a way, the personal hopes, beliefs, and arguments anthologized in Where Are We Now: Notes from Los Angeles are one such narrative. Waldie’s overall thesis seems to be that if we take time to understand L.A.’s failings and contradictions, if we can still find poetic imagery in the city’s tone of light, if we accept what we can and cannot fix, perhaps the city’s people can heal some of its broken joints.

If I have one gripe about Waldie’s argument, it’s that he doesn’t offer a more radical call to action. As the consequences of climate change and habitat destruction become more clear each day, it’s becoming equally clear that we have to do more than just notice and garden. We must totally reinvent how we think about the city and the ways we move through it. In the end, while I don’t think it was Waldie’s intent to innovate in this book, and he even disclaims his omissions in the Introduction, in reading the text in 2020, in this epoch of accelerated environmental catastrophe, the lack of a more forceful appeal makes the text feel slightly dated — of an era when we were worried, but not sinking as we are now.

A LOVING TANGENT ABOUT LAS VEGAS

Towards the end of this collection all about Los Angeles, Waldie includes an essay about Las Vegas. The ostensible thematic link between “The End of the West in Summerlin” and the rest of the text is its focus on a terminal suburban neighborhood in the American West, but the unexpected locational shift after 180 pages contained by California state lines suggests something else is going on here. Instead, I think Waldie has succumbed to a fever that I have succumbed to in my own writing about Los Angeles: a need to bridge the great emptiness between Los Angeles and Las Vegas through words on the page. L.A. writers can’t help but write about Las Vegas; there’s a strange, umbilical connection that stretches across the desert between the two cities.

This tether has been physically built out with a number of towns. From L.A. towards L.V., San Bernardino has spread towards the mountains, followed by Hesperia, Victorville, Barstow — but then the nothingness hits. The Mojave overwhelms development at the end of this municipal ellipses, and this is where the L.A. writer comes in: something as massive and mysterious as the desert can only be traversed by words. Understanding the peril of sticking stucco amid sand and yucca and seeking to suckle water from thin dry air, on the low stakes planes of our pages we pulley Las Vegas towards us with nouns and verbs and images and metaphors, tethering ourselves to a city stranded in the Mojave, or perhaps, anchoring ourselves to it. Even now I’m tempted to abandon this book review and go write about Las Vegas, that city that is clearly alien amid desert, while Los Angeles is too scared to admit it’s a city in a region without enough water.

Waldie’s digression doesn’t bother me because I enjoy reading and writing about Las Vegas, but I can see a less Sin City-inclined reader, saying wait, Now where are we?

Okay, carry on.

IN CONCLUSION

As a whole, D.J. Waldie’s Where Are We Now: Notes from Los Angeles is a book that reminds me of things I have written about this city. In other words, he notices facets of Los Angeles (and Las Vegas) that feel true and relevant to me as a creator, reader, and observer. Style-wise, while his writing tends to be more terse and factual that I typically like, he’s careful to contrast this workaday prose with lyrical twinkles, like gold flakes in a clear California creek. My few qualms with the text stem from issues created by the fact that its an older collection of disparate essays. In some cases, the persuasiveness of pieces is drained by their strange truncation, formatting, and obsolete topicality: notes like “New Urbanism 101”, “Ungovernable California,” “L.A. Literature”, and “Tragic Opera” feel oddly embryonic and outdated. But in total, despite these shallow nadirs, Where Are We Now, is a thoughtful charting of Los Angeles’s pulse from a particular angle and period. It’s up to the reader and the L.A. resident to decide what they want to do with it. I, for one, will be using Waldie’s notes as palimpsest for my view of the city from a different angle and a different moment.

In the end, while Waldie doesn’t explicitly answer his titular question — Where Are We Now in Los Angeles — after reading his book, the answer is clear: we are nowhere everywhere, and there’s no place I’d rather be.

ISBN of Edition Read: 1883318386

Notes of Oak Literary Blog Book Review Score for: Where Are We Now: Notes from Los Angeles by D.J. Waldie

7/10