Book Review

Book Review

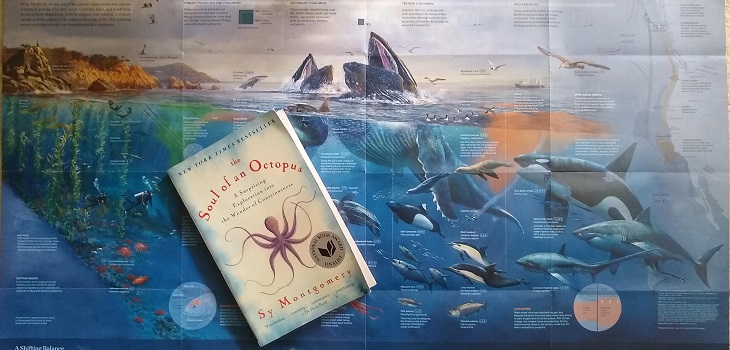

Human Hubris Dictates ‘The Soul of an Octopus’

A BOOK REVIEW OF SY MONTGOMERY’S NONFICTION TEXT – THE SOUL OF AN OCTOPUS: A SURPRISING EXPLORATION INTO THE WONDER OF CONSCIOUSNESS

Perhaps it’s because I just read Ill Nature, with its incisive critiques of humanity’s handling of animals, from scientists in the name of research, to zookeepers in the name of conservation. Or maybe it’s because my friends are cephalopod aficionados who don’t need to cosset octopuses in an aquarium to recognize their significance as living creatures. But for being a book entitled The Soul of an Octopus: A Surprising Exploration into the Wonder of Consciousness, Sy Montgomery’s 2015 text seems awfully fixated on oblivious humans, while offering only a surface-level, diluted view of the souls the title purports to give prominence to.

When I found this nonfiction nature book next to Ill Nature in the The Iliad Bookshop in North Hollywood, CA, I snatched it up precisely because I wanted to be schooled hard in octopuses’ magic. I usually gravitate toward the terrestrial rather than the aquatic, and felt that this text, with its “National Book Award Finalist” stamp and undulating octopus illustration on the cover, would plunge me into the poetic nuances of these intelligent underwater beings. So, so wooed by the idea of a philosophical engagement with cephalopods, I ignored the glaring “New York Times Bestseller” warning also on the cover, and didn’t even flip to the back blurb, where I would have seen that the author is a “popular naturalist.” If I had paid more attention to such marginalia, I could have guessed that The Soul of an Octopus is geared towards a general, self-centered public that needs to be pampered and persuaded to reach the basic fact that animals are conscious, living beings — something I (naively) thought we all already realized the first time we saw a fly watching us watching “it.”

In other words, The Soul of an Octopus offers no revelation for a reader like me. It is a book in which humans crowd in front of octopuses, both literally and figuratively, and which, in working towards its shallow goal of convincing people that animals are sentient beings, almost never grapples with the moral questions of keeping wild beings in captivity, subjecting them to questionable experiments, and intruding upon them in the wild. In fact, Sy Montgomery’s text lauds and leverages these practices in its quest to prove that octopuses are just as special as us wonderful humans.

The book revolves around Montgomery visiting the Boston Aquarium, where she has a backstage pass to interact with its wild-caught resident octopuses. These interactions generally involve Montgomery reaching into the tanks to touch the octopuses, and in turn, letting the octopuses “taste” her with suckered tentacles. Over the course of the book, the author visits with four main octopuses, named by the aquarium keepers as Athena, Octavia, Kali, and Karma. The author loves the octopuses so much, she spends more and more time at the aquarium, and in the process, befriends a core group of aquarium staff, volunteers, and their relatives, who all also reach in on “Wonderful Wednesdays” (as Montgomery dubs it) to touch the octopuses.

Montgomery repeatedly shares her new human friends’ life narratives, all the while emphasizing that they became such chummy buddies because of their mutual affinity for octopuses. These interjections of Homo sapiens stories are a glaringly obvious attempt to persuade the reader that octopuses are significant because they helped a group of people bond and learn more about each other. In pecking at this ad nauseum, Montgomery detracts from octopuses’ ipseity independent of humans, and turns the cephalopod into a mere plot device: the heavy focus on human friends drowns out Athena’s, Octavia’s, Kali’s, and Karma’s own narratives.

But that’s not all — Montgomery also makes it clear that she considers the octopuses to be her friends. Unfortunately, this type of thinking contributes to a popular problematic notion that in order for something wild to be appreciated and protected, the concept of it must be tamed through companionship, study, and/or ownership. Indeed, in The Soul of an Octopus, Montgomery misses a huge opportunity to challenge the misconception that we must understand a non-human organism in order for its life to be as significant as our own. Understanding adds significance to our existence, but the organism’s value in no way depends upon our appreciation of it.

Montgomery grows so infatuated with octopuses that, in addition to going scuba diving in the wild to find them, she considers “acquiring one of her own,” but alas, “expense aside — and it would cost thousands of dollars for the setup, food, and the octopus itself — there were the logistics,” and the fact that “if I had to travel…my husband would end up with the perilous responsibility for the delicate octopus,” so “in the end, I decided that, as great as a personal home octopus might be, it would be too risky for both the octopus and my marriage” (66-67).

I draw attention to this passage because it represents this book’s analytical failures: there’s zero engagement with the question of what it would mean to keep a wild creature locked in your home just because you like the species so much. The Soul of an Octopus is riddled with such blind-spots. At one point, Montgomery casually explains that:

Octopuses who have been experimentally blinded navigate flawlessly using their senses of touch and taste.”

pp. 219

The fact that the author focuses solely on the information gleaned from the experiment, but doesn’t dwell on the inherent problems of mutilating animals, is indicative of her perpetually myopic perspective — or at least a lack of courage to wrestle with the tougher questions that her facts and plot events evoke.

At another point, the plot’s primary conflict is that the young, exploratory octopus “Kali,” who has for months been stuck in a small, dark pickle barrel in the aquarium’s back area, “seems desperate to get out,” and so the staff must wrangle with the “problem of where to put her” (155). Later, as they continue to ponder over the issue, the author notes that, “As distressing as Kali’s situation is, Wilson [an aquarium volunteer] is well aware that people, too, must live with space constraints. Last week, in order for the hospice facility to accommodate new patients, his wife was moved to a different room” (166). These about-faces from the octopus to the book’s humans occur repeatedly, and as you can see here, offer an illogical salve for the octopus’s actual plight.

Eventually, the aquarium moves Kali to a new tank that may or may not be octopus-escape-proof, and whaddya-know, she escapes from it that night and dies in antiseptic on the floor — but whaddya-know, the aquarium almost immediately “ordered a new giant Pacific octopus” (183) even though the spatial issue clearly hadn’t been resolved. Even more disturbingly, this exact same thing happens again later in the book: as the aquarium now worries over where to move the elderly Octavia so that the younger Karma (THE OCTOPUS “ORDERED” ABOVE AND WHO’S NOW STUCK IN THAT SAME DAMN BARREL) can thrive, it turns out that the conundrum is amplified by the “new, small red octopus, the size of my hand, who had just arrived” (229).

Throughout all of this, Montgomery’s authorial engagement with the dilemma is filtered through the human characters’ emotions: the octopuses’ human-imposed predicament is worrisome only because the humans are worried about the octopuses’ predicament.

I’m not exaggerating when I say that Montgomery only twice engages with the moral issues of humans severing a wild animal’s natural path throughout the entire 250+ page text. The first comes after the author accompanies aquarium staff to pick up Karma at the airport, who was sent to them via a tiny box containing a bag of water dirty with the animal’s feces; Montgomery later asks the responsible trapper:

How does he feel about capturing animals in the wild and sending them to a life in captivity? He has no regrets. ‘They’re ambassadors from the wild,’ he said. ‘Unless people know about and see these animals, there will be no stewardship for octopuses in the wild. So knowing they are going to accredited institutions, where they are going to be loved, where people will see the animal in its glory — that’s good, and it makes me happy. She’ll live a long, good life — longer than in the wild.”

pp. 189

The author offers no analysis of this assertion, no delving into the possibility that the conscious octopus doesn’t want to be stuck at an accredited institution to be groped by tons of people, and that stewardship shouldn’t have to depend upon the mistreatment of individual octopuses. However, it turns out that Montgomery doesn’t evaluate the diver’s assertion because she agrees with it; this becomes clear in the only other passage in which she limply addresses the issue of captivity, as Octavia dies from old age in her aquatic cage:

We humans changed that natural path when we took Octavia from the ocean. Because of human intervention, Octavia never got to meet a male to fertilize her eggs. Despite her assiduous care, she would never see her eggs hatch. But we had fed her and protected her; we had provided her with marine neighbors, interesting views, and entertaining interactions with people and puzzles. We had kept her from hunger, fear, and pain. In the wild, virtually ever hour of every day would have brought the risk that a predator would bite off part of her body, as had happened to Karma, or that she would be torn limb from limb and eaten alive.”

pp. 221

It’s clear what humans have that animals don’t: hubris, such hubris. In The Soul of an Octopus, octopuses are pets to be petted, anthropomorphized, and displayed for stupid humans to ooh and ahh at, as the souls of the octopuses wilt beneath the belief that they must become ours for us to understand them.

Although there are flashes of well-written imagery in this text, especially when Montgomery is describing other animals in the aquarium, and although I recognize that the book is intended to curate a love for octopuses so that the general public can care enough to protect them, the text’s failure to focus on what I showed up to the theater for — the wonders of octopuses — and its overt catering to its human audience, make The Soul of an Octopus: A Surprising Exploration into the Wonder of Consciousness a disappointment for me.

ISBN of Edition Read: 9781451697711

Notes of Oak Literary Blog Book Review Score for: The Soul of an Octopus by Sy Montgomery

3/10

7 COMMENTS

I found your review fabulous. I really appreciate this perspective. I’ve been looking for books to help my son better understand empathy and kindness and your review makes me realize I do not want him to read this book. Humans are far too Speciesistic. I have no pets, ride no horses, am vegetarian. Peter Singer’s book How are we to live had a profound influence on me and confirmed my philosophy and ethics.

I couldn’t agree more! I couldn’t get over the breezy passerby morality of capturing wild, intelligent animals and stuffing them into barrels. The space issue is never resolved and, yet, more octopi are ordered with enthusiasm. The book spends a lot of time, cheerleading for and engaging with the continuous stream of octopus imprisoned within them. I’m not a vegetarian or animal rights person – but seriously! The book also spent so much time name dropping the educational title and age of every scientist in a way only a NY times best seller can. Coupled by a few less than feminist slips about pantyhose and bridal veils and I’m done. The title should be “The detailed souls of human who enjoy touching captive Octopus living in barrels”.

After a very sad visit to the Dallas Aquarium, I went into their gift shop and was drawn to The Soul of An Octopus. While the aquarium was beautifully done, I’ve always found animals of any sort that are captured and contained in small spaces beyond sad and the gift store was welcoming. I was drawn to The Soul of an Octopus and haven’t been able to stop reading it then doing my own Google searches looking for additional articles and photos. Capturing creatures for our enjoyment is cruel yet I learned so much from this book. I don’t have the guts to scuba and see these intelligent creatures in the wild and thankful for Sy’s descriptions and narrative.

Thank you so much for your insightful, honest review. I got 2/3 of the way through the book and got sick to my stomach and had to bail out. The reviews in the book were so positive and glowing, but I had a sinking feeling that I ignored when it was compared to the book, Hawk, which also bothered me. I just couldn’t get over how oblivious these “scientists” and caregivers were to the plight of the octopi they purported to care about so deeply. Ugh, hubris is right!

Thank you. This is everything I wanted to say but wasn’t eloquent enough to. In addition, I listened to the audiobook, meaning I suffered through the author’s awed, whispery voice for about 9 hours

Thanks for this great counter-perspective. It gives a lot to think about.. I am, however, unable to quite agree for the most part. Admittedly, this is, perhaps, easier to spot because of my probably equal parts western and foreign (African) perspectives.. In Africa, while we love nature, including animals, we may be a little more (or selectively) matter-of-fact in our view of their place and ours in this world. (I generalize a bit for “brevity”). It’s why, beyond this topic, we find some western ideals about animals quite, well, interesting. For example, vegans who aren’t just content to choose their nutritional Nirvana but insist the rest of us omnivores are barbarians. The pontifical revulsion is almost hilarious to observe.

Why is it OK to keep dogs but not octopuses? Because dogs are domestic? Yes, but not until they were domesticated perhaps some 23,000 years ago. Why do they get a pass? Albeit incorrigible all these millenia later and, granted, we have made much good of the situation, was it inherently wrong at the time to have domesticated them? If not, against the above logic, would there be a time when it’d OK to try and domesticate octopuses – if that were possible?

Nature is what it is. Many animals would kill and eat us without a thought if they could. It would be sad (to us) but just natural.. If they had the intelligence to cage and keep us, the stronger beasts would. – and that would be preferable to eating us as some certainly would. Why can’t our keeping some of them be natural too? Just something a stronget or more intelligent animal does in the ordinary course of it’s being here?

If we agree our concerns are only sentimental considering octopuses are intelligent creatures, fine. I’ll drop it. But it seems rather odd to me that we would ascribe a certain immorality to keeping a precious few samples of an uncountable population of fast breeding animals with a 6-month to 5-year lifespan (yes, I know a few deep-sea dwellers can hit 18 years).

A few Nigerian tribes eat dogs. As do some others in Vietnam, Switzerland, Korea, Thailand and other countries. I don’t but would be the first to admit that it is simply a sentimental thing. It’s unattractive to me because of all that dogs are to humans.. But for some others, it would just be intolerant to judge them.

Tangentially related is the argument by some that trees are sentient. And sentience is usually one of the factors proposed to proscribe consumption of certain animals. So we can’t eat animals and we can’t eat plants. The convoluted logic is nothing if not patent.

I think we should let people just be.. Only two (rather

obvious) things come to mind right now by way of qualifications:

We need to be extremely careful not to wipe out entire species of plants and animals – if possible.. But even in nature, sometimes, animals overgraze or over-hunt.. The result? Sometimes they migrate for new sources of food. Other times, they die off and become extinct. It’s all nature.

Secondly, we should make sure those animals kept as pets do not pose a hazard to us or others,

Beyond these two principles, let’s just all get along; let nature be..

And that includes humans keeping a few octopuses.

*****

Fun fact: according to the Scientific American, octopuses “have been around for at least 300 million years, surviving multiple mass extinction events. So there is a chance they might even outlive us here on Earth.”

I wouldn’t worry too much about them.

Hannah.

Your writings are always excellent and I greatly enjoy reading them. And so I feel the need to clarify that I offer my thoughts above very respectfully and apologize if they seem to come across otherwise. My address is to western attitudes generally. I’m very happy to have my views challenged as well.

My regards. .