Book Review

Book Review

‘The Japanese Linguistic Landscape’ is Quintessential Reading

A BOOK REVIEW OF NAKANISHI SUSUMU’S NONFICTION TEXT — THE JAPANESE LINGUISTIC LANDSCAPE: REFLECTIONS ON QUINTESSENTIAL WORDS (AUGUST 2019)

Recently published by Japan Library as an English translation, Nakanishi Susumu’s The Japanese Linguistic Landscape: Reflections on Quintessential Words is many things: essay collection, gathering of reflections, distilled wordstock, linguistic history, and philosophy for living. But above all, the text maps out a poetic landscape punctuated by beautiful word-landmarks. The waypoints on this map are both literal elements in reality, e.g. “folded layers of mountains,” “traditional hair ornament,” and “light blue,” and also the Japanese words that represent these real things. The poetry of these curated “quintessential words” amplifies the significance of the literal elements/phenomena they denote. That is, by considering the nuances of the language we use to describe our world, the author helps us chart powerful new intellectual and emotional connections to that world.

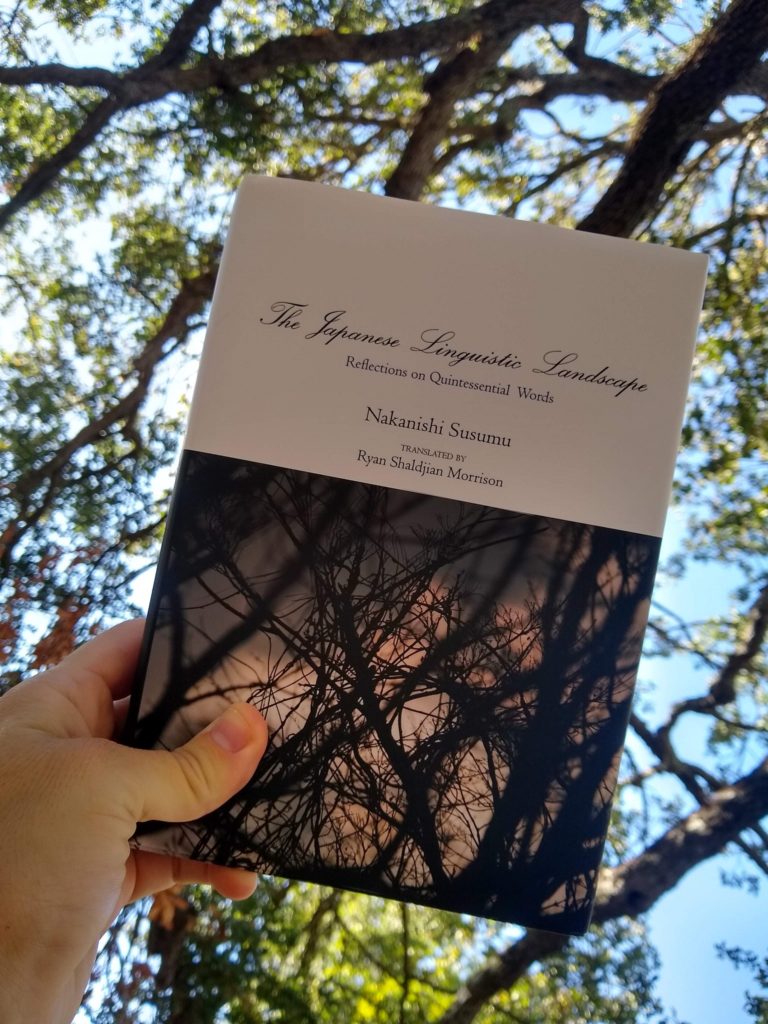

And I am quite happy to have Nakanishi Susumu as my guide on this linguistic journey, along with the text’s translator, Ryan Shaldjian Morrison. Susumu is the leading scholar of Japanese literature. His many accomplishments range from serving as the President of Osaka Women’s University, to receiving the Yomiuri Prize for Literature, the Japan Academy Prize, and the Order of Culture — Japan’s foremost prize for cultural contributions. Morrison, who holds a Ph.D. in Japanese literature from the University of Tokyo, currently serves as a tenured lecturer at Nagoya University of Foreign Studies.

Let’s pause to think about the magic of this book for a moment. A text written in Japanese about the intricacies of the Japanese language is transformed into a completely different language without losing its lyricism or meaning. Indeed, it acquires new import and poetic diction with each language it metamorphoses into. Thus, the act of translation reveals the persistence of an essential poetry across time and cultures — when it’s done well, as this text is, both in terms of its original ideas and the English vestments in which they appear.

The “Reflections” of the subtitle also aptly characterizes the illuminating nature of this book. The Japanese Linguistic Landscape glimmers with words about words. Each essay is, at core, a prismatic reflection of the focus term: from close analysis of one single word, Susumu hews hundreds more that all add color and dimension to the original term. In some way, this text acts as the Sugatami — “Full-Length Mirror” described in Chapter 3. This mirror “reflects psychological interiority and physical exteriority” (275), just as the author’s essays draw attention to both the written characteristics of these Japanese words (word parts, pronunciation, characters), and the hidden connotations and histories.

For both English and Japanese readers, writers, and word-lovers, The Japanese Linguistic Landscape is quintessential reading. Let’s journey through the textual terrain and find out why.

THE READING EXPERIENCE

As with The Music of Color, also published by Japan Library, The Japanese Linguistic Landscape is a beautifully printed book. The attention to detail that went into its publication manifests in a satisfying reading experience. The content is arranged into four sections, with the first three chapters composing the text’s bulk. They constitute a complete translation of Utsukushii Nihongo no fūkei (2008), while Chapter Four contains essays that can be found in Kotoba no kokoro (2016):

- Chapter One: Words about Nature: Earth, Sky, Wind, Water, and Fire

- Chapter Two: Words about the Four Seasons and Living Things

- Chapter Three: Words about the Human Heart

- Chapter Four: Essays on Modes of Living

These tidy categories coalesce to make a full-bodied, thematic reading experience. The first chapter forges a layered, elemental landscape textured with weather, light, ice, heat, air, and terrain. The second chapter builds on this with the feeling of the four seasons, along with the more tangible plants, birds, fish, and insects that inhabit them. With setting and atmosphere established, Chapter Three shifts into the human realm, mapping out the experiences, relationships, material things/objects, play, sensations, and actions that occur in these everyday environments. Finally, Chapter Four looks at aphorisms, mythological and artistic themes, and Buddhist legends. As a whole, the book feels like a perfectly crafted, delicate globe with the multi-dimensional topography of existence traced in detail.

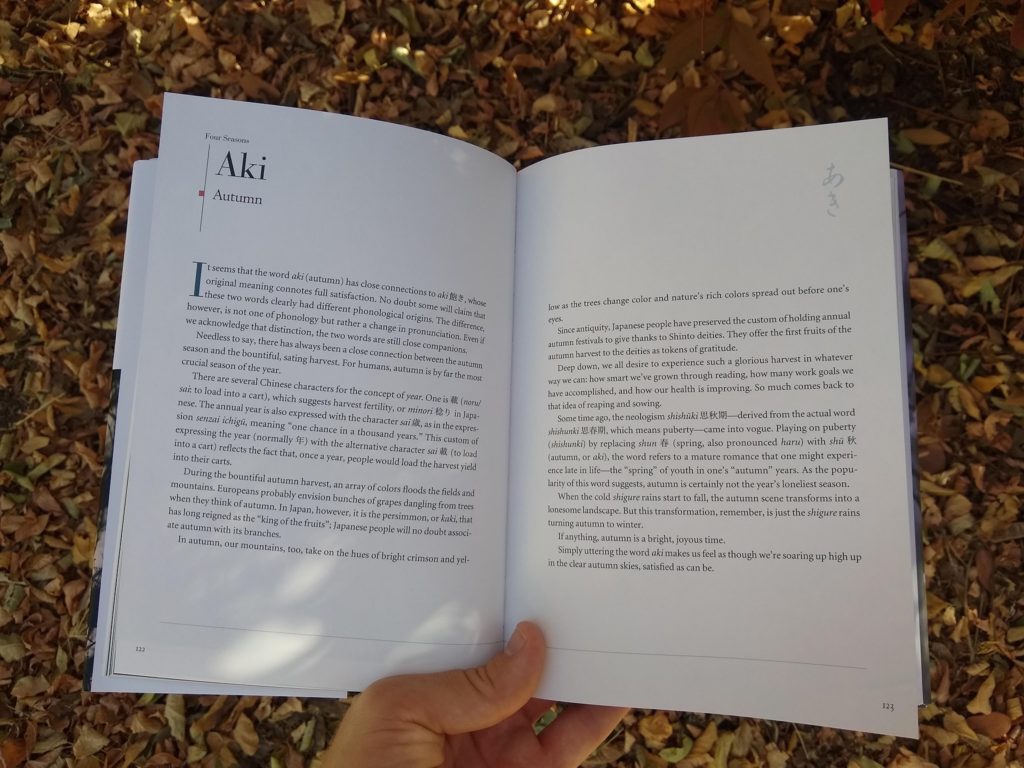

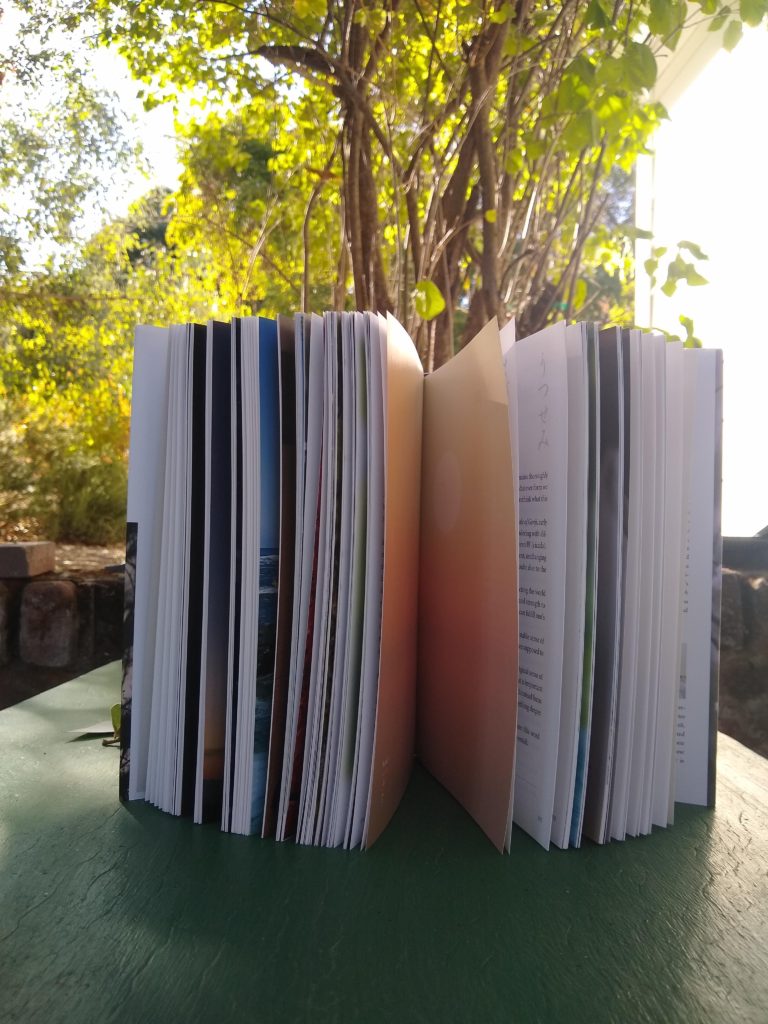

One of the genius aspects of the publication is that each essay on a “Word” fits neatly onto two pages. It’s a small design element, but no small feat, and perfectionists and bibliophiles alike will appreciate the pithy precision of this layout. Each word essay features a running header designating the word’s thematic category, followed by the showcased word in Romaji, and then its English translation, for easy perusing. Footnotes race across the page bottoms without intruding on the main content. Finally, two-page-spread photographs by Nakanishi Kimiko periodically punctuate the text, adding visual context to a number of the terms and creating colorful “breathers” amidst the word-heavy content.

Aesthetic care also went into the cover design. The flowing typeface of “The Japanese Linguistic Landscape,” along with the subtly blue “Reflections on Quintessential” subheading are mirrored by a photograph of tangled branch silhouettes backlit by blue-grey sky. The image evokes the written words just as written words evoke their extant counterparts. It’s a thoughtful presentation of natural calligraphy that motivated me to seek nature’s handwriting in my own backyard.

Overall, this book feels special in-hand. It’s something you’ll want to carry around to show off to all your literary friends and read aloud from at random. Something to set on your coffee table and admire for its elegance as an object, and then pick up and admire for the quality of its content even more. How nice it is that there are publishers who still care about making books that are both beautiful and insightful.

NAKANISHI SUSUMU ENERGIZES FAMILIAR PHENOMENA

After reading this book, I felt like I’d stepped into a new landscape where familiar moments and phenomena sighed with new meaning. Perhaps an even greater delight than discovering something new is discovering something anew and The Japanese Linguistic Landscape facilitates this undertaking.

Take, tasogare, which means “The Twilight Hour (When One Distrusts Even a Friend).” Susumu explains that tasogare consists of the three components “who,” “emphasis particle,” and “he,” and “you could translate it as ‘Who in the world is he?’ or, more idiomatically, ‘Who’s there?'” (42). The word thus contains within it an expression of the experience of that hour when lightlessness smudges familiar people and objects into strangers.

We’re all familiar with this fuzzy graphite time — we’ve all found ourselves peering into the obscurity, wondering, What is that in front of me? But rarely do we really think about how others become distorted and how we ourselves change at that time, becoming more cautious, questioning, and vulnerable in the lack of light. The word tasogare anchors us to that transformation in perception; it brings us closer to an electrifying moment.

Then there’s aburaderi, which translates to “Oily Sun on a Sultry Day.” I’m immediately captivated by the term’s tactile specificity, such that I can feel the unctuous sunshine slicking my skin beneath a sweltering sky. Susumu teases out the term, explaining that, “aburaderi refers to the scorching rays of sunlight that beat down ferociously on muggy days in midsummer — a phenomenon that many are surely familiar with” (32). Indeed, such familiarity tends to blur the actual, distinct experience of this feeling.

However, the articulation of the word counteracts that familiarity by containing within it tangible, temporal, and temperature sensations. Susumu explains that “abura” means “oil” or “fat,” while “deri” “denotes sunshine,” and contains connotations of “sunshine that feels as though you were being splashed with a thick, greasy-like substance” (33). With evocative descriptions such as this, the essay transforms the word aburaderi into an imagery-rich concept we can recite on muggy midsummer days to poeticize the sensation of the sun.

While all the words in The Japanese Linguistic Landscape possess a poetic essence independent of Susumu, his expertise enables us readers to see this poetry we’d been missing both in our experiences and our expressions of them. And the book doesn’t just offer insight into the piquancy dwelling in the ninety words contained between the covers — it also invites us to apply equal attention to the secrets of other words used everyday. Practitioners of any language can do this; across the world, every tongue holds a lyricism within its linguistic bones. We may not have the same breadth and depth of knowledge as Susumu — and indeed, his understanding of the Japanese language’s historical intricacies is impressive — but we can begin by reading this book and cultivating a curiosity about our vocabulary.

GRACEFUL PROSE ABOUT LANGUAGE

In The Japanese Linguistic Landscape, not only are most of the words Susumu has selected inherently poetic, his analyses of them are rendered in poetic prose. This is not a dry linguistics textbook. The best adjective I can think of to describe his handling of this sophisticated subject is “graceful.” Examples of some poignant essays include:

Uzumibi — “Embers under Ash”

This term has fallen out of usage because the practice it arose from isn’t common in contemporary Japan. Susumu explains that:

Long ago, people used to put charcoal (sumi) into a hibachi brazier to keep themselves warm…A person would take the remaining embers of charcoal and then reuse them as the source for the next fire. The idea was to bury the smoldering embers under ash to keep the fire alive. When one would sift through the ashes, they would find a glow underneath, like a bright-red ruby revealing itself. People used to call that hidden fire the uzumibi, or ‘buried flame’…The term uzumibi refers to a flame that burns forth continuously yet inconspicuously, creating a beautiful radiance at once exquisite and invisible…The poignant notion of uzumibi offers a rich metaphor for our human lives.”

–The Japanese Linguistic Landscape, pp. 98-99

As you can see from just these extracted bits, the essay is lush with history, figurative language, and philosophical elucidations. I haven’t been around a fire in years, but the sensory imagery instantly evokes the warm gem of the smoldering flame tucked under soft grey ash, such that the uzumibi seems to glow within the soft grey matter of my own mind. Indeed, while the practice of burying a glowing coal may be nearly obsolete, Susumu proves that the connotative “notion” of the word remains bright and relevant, such that we can utilize the term to restart the fire of our selves.

Mugetsu — “No Moon”

Every year, on September 15th, the mid-August harvest moon rises into the sky, only to be erased by thick clouds. To celebrate its hidden presence, the pre-modern Japanese coined the term mugetsu, which fuses “mu” (no, nothing) + “getsu” (moon). Susumu explains that:

They effectively brought the invisible mid-August harvest moon into existence by specifically christening it the mugetsu…In short, the mugetsu somehow exists in a state of non-existence. It is being in non-being. It is the moon that both is and yet is not. The term mugetsu captures that phantasmagorical moon, a captivating contradiction.”

–The Japanese Linguistic Landscape, pp. 48

The paradox — the presence of the absence — depends on the word. In other words, mugetsu calls into being both the missing moon and the contradiction of that missing moon. It’s a powerful demonstration of language’s ability to not just evoke but also invoke, and our recognition of this nuance depends upon Susumu’s careful selection of this “quintessential” word, along with his eloquent insight into its inherent polarity.

Ubatama – “Pitch-Black, Nocturnal”

My favorite essay is a poetic, imagery-intensive exploration of the word ubatama, which originally referred to the blackberry lily plant (now called karasu-ōgi). Ubatama, which “appears in classical literature as early as the Kojiki (Book 1),” has since become “an epithet for evoking the images of pitch-black night” (166). I’ll quote Susumu extensively:

Karasu-ōgi has leaves that open out flat, like a fan (ōgi), as they unfold. The ends of its branches grow red flowers. But when you pluck its fruit in autumn, you can see that the seeds are actually little round, black balls a mere three or four millimeters in diameter.

These particle like pieces of fruit, appearing almost to have a black-lacquer finish, resemble little black beads — in a way, little black souls, or tama 魂. That’s why ubatama is sometimes written as black bead or crow bead. The karasu of karasu-ōgi, too, comes from its real color: the so-called karasu-iro, or ‘crow color.’

…It is only natural then, that ubatama should come to symbolize the pitch-black sense of mystery that permeates the dark night. You might even wonder if the ubatama could be the spirit of night itself.

…In the West, the dandelion, or tanpopo in Japanese, is sometimes described as a fragment of sun fallen to Earth. In that sense, the inspiration for the word ubatama could have been a shard of the night, crumbling off and spilling earthward.”

–The Japanese Linguistic Landscape, pp. 166-167

In The Japanese Linguistic Landscape, Nakanishi Susumu doesn’t simply explain words — he paints them with sensuous sentences. The glistening, globular onyx fruit emerges from the page, from history, and from nature via his cogent descriptions. He then carefully takes this precise imagery and elevates it through philosophical ruminations on the word’s symbolism, making a distinction between the “dark night” and the “pitch-black sense of mystery” that dwells in that night.

Surrounding ubatama in this essay are the brushstrokes of other words, which are vivid fragments in and of themselves, and which also draw out the full iridescence of the keyword through connections and contrast; the dandelion as a “fragment of sun” deepens the darkness of the “shard of night” that is ubatama. Beyond the pleasure of reading a linguistic essay that feels like a painting, Susumu’s picturesque writing style is an effective way to reinforce the complex meanings of quintessential Japanese words. What a delight it would have been to learn words like this, in this way, in school.

A NETWORK OF WORDS LIKE ROADS ON A MAP

There are ninety words listed in the Table of Contents of The Japanese Linguistic Landscape, but as is evident in the previous essay, Susumu introduces us to countless others along the way. After all, many words contain others within their hearts and are always holding a variety of conversations with dozens of related terms. Thus, the textual map of language that is this book doesn’t just include quintessential waypoints, but also traces the web-like word-roads branching from these lexical landmarks.

Sometimes these additional terms encompass a word part that’s also in the primary word. For example, when we learn about sabiru, which means “to rust,” we also learn that a “sabishii fūkei (lonesome landscape) is infused with sabi: it has acquired ‘rust'” (212). Susumu demonstrates that morphemes are keys to unlocking the poetic imagery of whole words — and once one word is unlocked, it can shed light on related terms.

In other instances, the author presents us with alternate terms for the focus term. Usually, via contrast, these alternatives reveal the greater lyric potency of the primary word. For example, he explains that furakoko is “an old word for a hanging swing, or what is today called the buranko…The first parts of the words, fura and bura, have radically different connotations. Fura is elegant and refined, while bura has an unclean, vulgar ring on account of its muddied “b” sound…If the word buranko evokes the sense of a swing dangling loosely there with no one sitting in it, furakoko gives the feeling of a swing swaying back and forth in a leisurely, elegant way” (238). Through such juxtaposition, the author teaches us that language affects our mental image of real things. A mere swing, a dangling, jangling plaything, can change radically depending on the word we use to describe it.

If we conceive of an object with a paltry term, the object in turn becomes withered in reality. But if we speak and think in beautiful terms, the words enunciate the poetry waiting to be noticed in reality. And the import of all this becomes exponentially greater when we remember that language is a network, with each word we choose igniting the next. Susumu enables us to see both the character of individual words and the many links branching from each of those words.

THE JAPANESE LINGUISTIC LANDSCAPE ABOUNDS WITH WORD JOY

When it comes down to it, The Japanese Linguistic Landscape is also an argument for the necessity of poetry. The book doesn’t just teach us about words; it teaches us why it’s important to think about words. Susumu expresses his philosophy in aphoristic statements that every poet should have ready in their back pocket for when naysayers complain that, “Poetry doesn’t do anything.” A few of my favorites from the book include:

- “Words slowly acquire their beauty over the centuries, through the process of being warmed and polished in the hearts of the people using them” (216).

- “To my mind, a beautiful word is one that gracefully bridges the gap between objective fact and subjective human impression” (68).

- “Speaking in beautiful phrases naturally beautifies our character, after all” (158).

I completely agree.

Indeed, one of the pleasures of reading this book is seeing Susumu’s own pleasure in the functional magic of words. As a writer, I love language and its ability to enhance perception, and it’s always a joy to hear from other people who love language. Susumu regularly conveys his affection through anecdotal exclamations, such as, “Every time I think of it, I always enjoy the fact that little, round, potato-like taro roots, known as satoimo in Japan, also go by the name kinukatsugi (kinu, or ‘clothing,’ and katsugi, or ‘wear’ or ‘don’)” (156). His gleeful insight about the quirky connotations of a wee, chubby root become the reader’s, facilitated by the intimate use of the first-person voice amidst the more formal investigation of the word parts.

The Japanese Linguistic Landscape also brims with allusions to literary texts. This is important because we tend to encounter words embedded in books, where they shimmer in context. The author most often turns to that highest of all literary arts, poetry, and specifically, haiku, relying on both historical and modern examples. The poems illuminate the words’ meanings and reveal just how long many of these terms have been captivating artistic minds.

For example, in the aforementioned Mugetsu — “No Moon” essay, Susumu explains, “Haiku poetry prizes the elegance of bringing things into existence by enunciating absence, nothingness” (49). He goes on to feature a poem by Shida Sokin from the collection Yamahagi (Bush Clover):

Santō ya

mugetsu no sora no

soko akari.

Range of mountains–

in the moonless sky

an illusory glow.

With this allusion, we not only learn about the methods/goals of haiku writing, we also get to enjoy the experience of reading a well-crafted poem. We get to see mugetsu in action like the shadow of a salmon shifting underwater. Further, just as the literary form manifests the inherent paradox of mugetsu — invoking an absence — the allusion doubly invokes this for the reader of The Japanese Linguistic Landscape via the word itself and the poetic vessel that holds it. Finally, although the English translation necessarily uses different words, it harbors its own poetic elements, such as the assonant echoing of “moonless” in “illusory,” which reinforces the elusive presence of the missing moon. This musicality also reinforces the aforementioned idea of an essential poetry persisting across translations. It’s all a wonderful entanglement of illusion and reality, poetry and prose, language and meaning, and reader and writer, and there are many such instances of allusive illumination throughout the text.

IN CONCLUSION

Overall, The Japanese Linguistic Landscape is a vividly written, carefully translated, and beautifully printed text. There’s so much noteworthy information contained within, I had to hold myself back from citing entire essays while writing this review.

Indeed, my only critique involves Chapter Four, which, as mentioned above, consists of content from a different book than the first three chapters. These five concluding essays, which focus on “Modes of Living,” and which constitute less than 20 pages, were interesting, but didn’t nurture the same poetry as the chapters focusing on “words.” In other words, they didn’t seem as “quintessential.” The mode-of-living essays ranged over wider ground than the word essays, and thus had less of the highly concrete and specific imagery that I enjoyed so much in the first three chapters. Susumu is at his best when he’s holding the jewel of a single term in his hand and describing the way its facets shimmer in the light.

The poet Mary Ruefle has written that, “Every word carries a secret inside itself; it’s called its etymology. It is the DNA of a word. To crack or press a word is to use its etymology to reveal its secrets, all still embedded in the direct action of ancient and original metaphor (Madness, Rack, and Honey pp. 91). In The Japanese Linguistic Landscape, Nakanishi Susumu delicately splits open quintessential Japanese words and reveals exquisite secrets that have palpitated for centuries within each lexeme’s gossamer cocoon. How lucky we are to have this book that gathers and gifts us these fluttering, glowing cores.

ISBN of Edition Read: 9784866580685

Notes of Oak Literary Blog Book Review Score for: The Japanese Linguistic Landscape: Reflections on Quintessential Words by Nakanishi Susumu

9/10

3 COMMENTS

Excellent review.

fascinating post

This book looks wonderful. I ordered it immediately. It will help with my project. I’m writing a book of pairings based on a series of Japanese color-scheme books which I have been painstakingly translating for myself with the help of Google Translate and my own limited knowledge of the Japanese language. The authors of the color scheme books, Teruko Sakurai and Naomi Kuno, frequently use poetic Japanese color words. They’re fascinating to learn about. I’ve been getting a crash course in Japanese culture in the process. I can’t wait to read this book. Thank you so much for your thorough and thoughtful review.